How one neighborhood reduced its carbon emissions by 1,600 metric tons

Published in Lifestyles

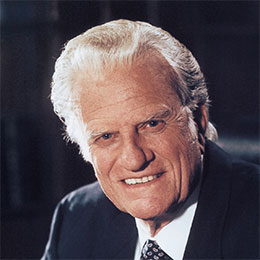

MINNEAPOLIS -- Mary Britton remembers the distress she felt in the summer of 2019, when images of huge wildfires in Spain and Australia flared up on the internet.

The fires were made worse by climate change, studies showed. Britton, a financial analyst living in Minneapolis, responded by reducing her own carbon footprint.

She insulated her attic, replaced her gas water heater with an electric one and made other energy efficiency upgrades to slash the amount of natural gas she burned to heat her home. She also began sharing information about the upgrades with fellow Prospect Park neighborhood residents and pointed them to the local and federal rebates available to save money on the work.

The effort paid off. Residents of Prospect Park used 29% less natural gas between 2019 and the end of 2024, according to CenterPoint Energy, while citywide gas use fell by 20% during that period. That means Prospect Park cut its annual carbon emissions by about 1,620 metric tons, roughly the output of 378 gasoline cars in a year.

The Trump administration has turned away from the collective fight to slow global warming, shunning efforts by the United Nations and reversing federal policies that encouraged clean energy. In response, some Minnesotans who care about climate action are turning their attention to changes they can make locally.

Britton said she’s already in talks with other neighborhood associations and nonprofits to do similar work in their communities.

“That’s the exciting thing — these people feel part of something bigger,” she said. “Everybody waiting for somebody else to do something … that’s not going to work.”

In July, Congress rescinded hundreds of billions of dollars in federal tax credits established by the Inflation Reduction Act. Among the affected credits are the Energy Efficient Home Improvement Credit and the Residential Clean Energy Credit. Claiming those incentives can save homeowners up to 30% off the total cost for various home improvements, including replacing windows, putting in new insulation and installing heat pumps or solar panels. Those credits, which were previously available until 2032, now expire at the end of the year.

Wedged between the University of Minnesota’s St. Paul and Minneapolis campuses, Prospect Park is perhaps best known for its Witch’s Hat tower. The hilly neighborhood of 875 residential properties spans roughly a square mile.

For Britton, focusing on the changes she can make at the local level, even just in her neighborhood, has helped her cope with the Trump administration’s cuts to federal climate and clean energy programs this year, she said. Some of her neighbors expressed similar sentiments.

Nan Kari, who lives down the street from Britton, said the work she’s done to reduce the carbon emissions of her home have been cathartic for her. After coming across Britton’s campaign, she said, she replaced 11 windows and a door. She also replaced her old HVAC system with a heat pump and a backup furnace.

“That’s what it takes, citizen action … for a larger public good,” Kari said, adding that she believes local action is especially important “in the absence of federal leadership — or corporate leadership, for that matter.”

John Wike, another Prospect Park resident, said he came across Britton’s campaign in the neighborhood email. It persuaded him to install insulation in his walls and attic last year. He also insulated part of his roof this month, he said, and will soon install an electric water heater.

Helping the environment was his primary motivation, but the home improvements have also made his century-old house more comfortable, Wike said. “Especially with insulation in an older house in Minnesota, it’s made a huge difference with cold drafts in the winter and heat in the summer,” he said.

“One of our dogs has passed away recently, but we’re getting another dog. And it’s like, you don’t want to have dogs in the house, where it’s 90 degrees in the kitchen,” Wike added.

The improvements weren’t cheap. Both Kari and Wike each spent tens of thousands of dollars for the work, even with the local and federal rebates. But the incentives were a big help, they said, saving them each about $11,000 total. Wike said he expects the federal credits alone to save him $2,400.

CenterPoint Energy said in a statement that Prospect Park is one of the neighborhoods where the company is seeing increased participation in its rebate programs. The utility also noted that 2019 was a below average year for temperatures, while 2024 was an above average year, which influenced the amount of gas used by homeowners.

Still, Prospect Park residents like Kari and Wike view the outcome as a testament to Britton’s hard work, which involved regular email blasts through the neighborhood association and visits to local events and church services.

Britton said one thing that she believes helped her campaign was that she never told people what to do — she only provided them with information and resources.

“People want to do the right thing, but they don’t want to be lectured,” Britton said. “I never told people to turn down their thermostat.”

Minneapolis residents in other parts of the city are taking note of Britton’s campaign as well.

“We’ve been copying Mary’s approach from Prospect Park to engage neighbors in my own Corcoran neighborhood,” said Sean Gosiewski, executive director of Resilient Cities and Communities, an environmental advocacy group. At least 10 residents in his neighborhood have installed heat pumps this year, thanks to the outreach, he said.

“We feel Prospect Park is the leading example,” Gosiewski said.

©2025 The Minnesota Star Tribune. Visit at startribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments