Kaiser workers launch war against AI, protesting potential job losses and patient harm

Published in Business News

Workers of one of the most powerful unions in California are forming an early front in the battle against artificial intelligence, warning it could take jobs and harm people's health.

As part of their ongoing negotiations with their employer, Kaiser Permanente workers have been pushing back against the giant healthcare provider's use of AI. They are building demands around the issue and others, using picket lines and hunger strikes to help persuade Kaiser to use the powerful technology responsibly.

Kaiser says AI could save employees from tedious, time-consuming tasks such as taking notes and paperwork. Workers say that could be the first step down a slippery slope that leads to layoffs and damage to patient health.

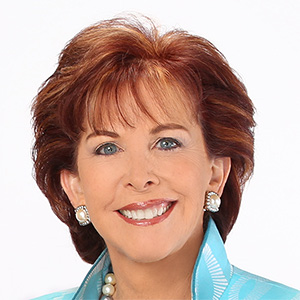

"They're sort of painting a map that would reduce their need for human workers and human clinicians," said Ilana Marcucci-Morris, a licensed clinical social worker and part of the bargaining team for the National Union of Healthcare Workers, which is fighting for more protections against AI.

The 42-year-old Oakland-based therapist says she knows technology can be useful but warns that the consequences for patients have been "grave" when AI makes mistakes.

Kaiser says AI can help physicians and employees focus on serving members and patients.

"AI does not replace human assessment and care," Kaiser spokesperson Candice Lee said in an email. "Artificial intelligence holds significant potential to benefit healthcare by supporting better diagnostics, enhancing patient-clinician relationships, optimizing clinicians' time, and ensuring fairness in care experiences and health outcomes by addressing individual needs."

AI fears are shaking up industries across the country.

Medical administrative assistants are among the most exposed to AI, according to a recent study by Brookings and the Centre for the Governance of AI. The assistants do the type of work that AI is getting better at. Meanwhile, they are less likely to have the skills or support needed to transition to new jobs, the study said.

There are millions of other jobs that are among the most vulnerable to AI, such as office clerks, insurance sales agents and translators, according to the research released last month.

In California, labor unions this week urged Gov. Gavin Newsom and lawmakers to pass more legislation to protect workers from AI. The California Federation of Labor Unions has sponsored a package of bills to address AI's risks, including job loss and surveillance.

The technology "threatens to eviscerate workers' rights and cause widespread job loss," the group said in a joint letter with AFL-CIO leaders in different states.

Kaiser Permanente is California's largest private employer, with close to 19,000 physicians and more than 180,000 employees statewide. It has a major presence in Washington, Colorado, Georgia, Hawaii and other states.

The National Union of Healthcare Workers, which represents Kaiser employees, has been among the earliest to recognize and respond to the encroachment of AI into the workplace. As it has negotiated for better pay and working conditions, the use of AI has also become an important new point of discussion between workers and management.

Kaiser already uses AI software to transcribe conversations and take notes between healthcare workers and patients, but therapists have privacy concerns about recording highly sensitive remarks. The company also uses AI to predict when hospitalized patients might become more ill. It offers mental health apps for enrollees, including at least one with an AI chatbot.

Last year, Kaiser mental health workers held a hunger strike in Los Angeles to demand that the healthcare provider improve its mental health services and patient care.

The union ratified a new contract covering 2,400 mental health and addiction medicine employees in Southern California last year, but negotiations continue for Marcucci-Morris and other Northern California mental health workers. They want Kaiser to pledge that AI will be used only to assist, but not replace, workers.

Kaiser said it's still bargaining with the union.

"We don't know what the future holds, but our proposal would commit us to bargain if there are changes to working conditions due to any new AI technologies," Lee said.

Healthcare workers say they are worried about what they are already seeing can happen when people struggling with mental health issues interact too much with AI chatbots.

AI chatbots such as OpenAI's ChatGPT aren't licensed or designed to be therapists and can't replace professional mental health care. Still, some teenagers and adults have been turning to chatbots to share their personal struggles. People have long been using Google to deal with physical and mental health issues, but AI can seem more powerful because it delivers what looks like a diagnosis and a solution with confidence in a conversation.

Parents whose children died by suicide after talking to chatbots have sued California AI companies Character.AI and OpenAI, alleging the platforms provided content that harmed the mental health of young people and discussed suicide methods.

"They are not trained to respond as a human would respond," said Dr. Dustin Weissman, president of the California Psychological Assn. "A lot of those nuances can fall through the cracks, and because of that, it could lead to catastrophic outcomes."

Healthcare providers have also faced lawsuits over the use of AI tools to record conversations between doctors and patients. A November lawsuit, filed in San Diego County Superior Court, alleged Sharp HealthCare used an AI note-taking software called Abridge to illegally record doctor-patient conversations without consent.

Sharp HealthCare said it protects patients' privacy and does not use AI tools during therapy sessions.

Some Kaiser doctors and clinicians, including therapists, use Abridge to take notes during patient visits. Kaiser Permanente Ventures, its venture capital arm, has invested in Abridge.

The healthcare provider said, "Investment decisions are distinctly separate from other decisions made by Kaiser Permanente."

Close to half of Kaiser behavioral health professionals in Northern California said they are uncomfortable with the introduction of AI tools, including Abridge, in their clinical practice, according to their union.

The provider said its workers review the AI-generated notes for accuracy and get patient consent, and that the recordings and transcripts are encrypted. Data are "stored and processed in approved, compliant environments for up to 14 days before becoming permanently deleted."

Lawmakers and mental health professionals are exploring other ways to restrict the use of AI in mental healthcare.

The California Psychological Assn. is trying to push through legislation to protect patients from AI. It joined others to back a bill requiring clear, written consent before a client's therapy session is recorded or transcribed.

The bill also prohibits individuals or companies, including those using AI, from offering therapy in California without a licensed professional.

Sen. Steve Padilla (D-Chula Vista), who introduced the bill, said there needs to be more rules around the use of AI.

"This technology is powerful. It's ubiquitous. It's evolving quickly," he said. "That means you have a limited window to make sure we get in there and put the right guardrails in place."

Dr. John Torous, director of digital psychiatry at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, said people are using AI chatbots for advice on how to approach difficult conversations not necessarily to replace therapy, but more research is still needed.

He's working with the National Alliance on Mental Illness to develop benchmarks so people understand how different AI tools respond to mental health.

To be sure, some users are finding value and even what feels like companionship in conversations with chatbots about their mental health and other issues.

Indeed, some say the AI bots have given them easier access to mental health tips and help them work through thoughts and feelings in a conversational style that might otherwise require an appointment with a therapist and hundreds of dollars.

Roughly 12% of adults are likely to use AI chatbots for mental health care in the next six months and 1% already do, according to a NAMI/Ipsos survey conducted in November 2025.

But for mental health workers like Marcucci-Morris, AI by itself is not enough.

"AI is not the savior," she said.

©2026 Los Angeles Times. Visit at latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments