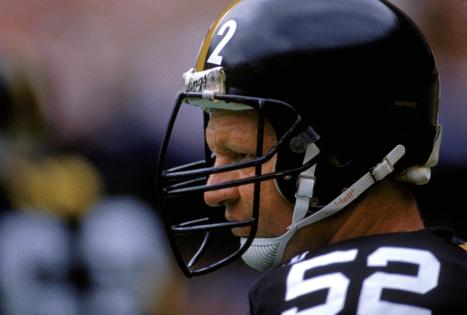

Jason Mackey: Mike Webster's family works to ensure his legacy is not lost

Published in Football

PITTSBURGH — Whenever Pam Webster feels consumed by the stress — concerns over food, money or family feeling like too much — she can always count on her son, Garrett, for a laugh.

"His best line whenever I'm complaining, when we don't know how we're going to get food or the budget's tight, he'll say, 'You should have married a football player,'" Pam said.

Pam, of course, did. Arguably the best center ever and a Steelers legend, Iron Mike.

But the legacy of Mike Webster — in many ways a tragedy but also an important eye-opener for how we view concussions — stretches far beyond the football field, his struggles offering an inconvenient truth when it comes to the risks of repeated head trauma.

It's hard to believe it's been 20 years since Dr. Bennet Omalu's transcendent study of Webster's brain appeared in the journal "Neurosurgery," Garrett and Pam told me while we met for coffee recently at a Starbucks near the Moon Township home they share.

The road for the Webster family has never been easy, whether that has involved the chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) discovered by Dr. Omalu, fighting the NFL for concussion-settlement dollars, a relationship with the Steelers that became strained due to Mike's erratic behavior, or honoring the legacy of a loved one lost way too soon.

"You could make the argument that Dad's one of the most important players ever in the NFL because of what happened after he retired," Garrett said. "You have to take a certain amount of pride being part of that legacy."

Pam, Garrett and his three siblings — Brooke, Hillary and Colin — will always take pride in keeping the memories of Iron Mike alive. But it's not easy. It's never been easy.

Mike wasn't fancy, Garrett and Pam will tell you with pride. He preferred Eat'n Park, Kings or Denny's to any fancy steakhouse. Waffles with strawberries and whipped cream was one of Mike's go-to orders. His ability to turn down a root beer float: terrible.

It's one of several reasons why Mike became so popular here, along with his talent, lunch-pail attitude and impenetrable toughness, the endearing — and healthier — side that Garrett tries to help people remember via social media.

While stories of Mike sleeping in his truck or selling his Super Bowl rings — not to mention the failed business ventures or the awkward Pro Football Hall of Fame speech in 1997 — tend to frame the narrative of Mike's post-retirement issues, Garrett makes sure to point out the positives, too.

There are pictures of Mike and the kids when he was well, the John Wayne references and funny 1980s photos emanating from Garrett's X account (@Bigweb52). Through what Garrett chooses to share, it's easy to see Mike's sense of humor and the love in his heart, the quintessential family man not yet sick.

"One of the things with Dad, even though he went through his dark times, he tried to stay positive," Garrett said. "Especially with Dad's story, there's a lot of tragedy with it. I try to point out that there were good times, too."

And stuff that has changed for the better.

Twenty years after Dr. Omalu's paper was published and the NFL has changed its tune on the link between football and CTE, we have seen progress made, whether it's with baseline testing, concussion spotters, the crackdown on illegal hits or helmet technology developed to protect players' brains.

Is it enough? Of course not.

But Pam and Garrett believe Mike would be pleased to see what has happened since Dr. Omalu found large accumulations of tau protein in the former center's brain, the repeated hits to the head undoubtedly contributing to Mike's late-in-life problems with cognitive impairment, depression, drug abuse, erratic behavior and more.

"A lot of the steps are admirable with concussion treatment and prevention," said Garrett, who used to work as an administrator for the Brain Injury Research Institute, which studied the long-term impact of repetitive head injuries. "You've seen in the last few years people starting to understand head injuries affect so many different things."

It's impossible to discuss concussions and the risk of serious brain injury in football without Mike front and center. He's long been the poster child, although the Websters were never treated as such by the NFL.

It took four years after Mike died from a heart attack at age 50 for the Websters to finally win a prolonged legal battle with the NFL's disability plan. But even then, the financial award (between $1.5 million to $2 million) was only a portion of what the Websters should've received.

That's because when the NFL reached its $1 billion-plus concussion settlement a decade or so ago, it was limited to players who died after 2006.

"You can't help but feel that personally," Pam said.

But in what has become a common theme for the Websters, they walked so other NFL players and their families could run, Mike's story serving as a cautionary tale and living proof that things need to change when it comes to concussions in football — for player safety and also for the family members CTE can affect.

It hasn't led to riches or fame, but Garrett and Pam know their struggles have improved things for others.

Hardly a week goes by where someone doesn't message Garrett or Pam on social media, either complimenting the way they choose to honor Mike, asking questions or sharing stories of their own plight. It could be scary to some. Yet that's all the Websters have known pretty much since Mike's Steelers career ended.

"You take pride in being the first domino that fell, to get it for other people," Garrett said.

"If it wasn't for Mike, this issue wouldn't have come up until years later," Pam added. "Mike literally gave his life for a greater cause. He affected so many people, and we try to honor him for that."

That hasn't been easy.

Due to the effects of CTE, Mike's post-playing life became a troubled existence. He was homeless or lived out of his truck for stretches. In 1999, Mike was charged with forging 19 prescriptions to obtain Ritalin, sold his Super Bowl rings, would occasionally disappear for weeks at a time, lost money on failed business opportunities and could be difficult to understand.

Mike had a variety of other health issues (which he often kept private), and the result of his entire situation once football went away became a source of stress for the family.

"With what happened to my dad, it affected the whole family," Garrett said. "I know if Dad was healthy and he was sitting here now, he'd say, 'I'm horrified that the things I did when I wasn't in the right frame of mind affected my family so much.'"

There've been strained relationships within the family, "emotional and mental-health issues," and financial concerns dating back to Mike's post-playing career, when his erratic behavior wiped out their savings.

As the attention on concussions has grown over the past 20 years — though never enough — the Websters maintain their modest existence.

Garrett delivers pizza for Angelia's in Moon Township, a job he's held for the past 15 years. The concussion-research gig didn't work out because Garrett said he wasn't any good at it. Pam, who turned 74 in June, cleans houses. They do their best to make ends meet with Social Security and an annuity.

"I went to a doctor a couple years ago," Pam stated. "He asked me, 'When was the last time you didn't have stress in your life?' I said, 'Maybe 30, 40 years ago.' It's part of what we've lived through.

"There was healthy Mike and unhealthy Mike. It's affected us and how we live day-to-day. It's not your typical story. Everything that happens to us seems to happen to the extreme. It's really hard to process a lot of what has happened, especially as I age."

Dr. Omalu's paper might've changed the game with how we view CTE or treat concussions in athletes. However, there's no playbook for what the Websters have encountered.

Similar to Mike as a player, they've relied on toughness and honesty as they crashed through the wall, paving the way for others.

It has also created a unique relationship between Garrett, 41, and Pam.

"Who lives with their 74-year-old mom?" Pam wondered aloud. "But we have a good time. We both have a love of World War II and history ..."

"Which Dad would find hilarious," Garrett interrupted. "I like to tell her that she's slowly turning into Dad. Bent fingers ... she's sick and doesn't want to go to the doctor. That's what Dad would do."

"Glue a tooth back in," Pam added, laughing.

Though the money isn't plentiful and the Websters have had their share of familial problems, they are in a different spot when it comes to celebrating Mike's Steelers legacy.

Due to how things fell off following his final NFL season in 1990 (with the Chiefs), his relationship with the Steelers became strained. He expected a coaching job that never materialized. After years of strange behavior, the organization kept Mike at arm's length.

Pam and the kids couldn't escape Mike's mental deterioration — and that, too, became tough to own or process.

Having grown up in Pittsburgh, there was a period where Garrett — who went to Moon Area High School — said, "You almost felt ashamed if someone said something nice about your dad because of how bad things went."

Much has changed on that front.

Mike's troubles weren't small or pretty, but they've become more understandable with medical research and time. The difficult relationship with the Steelers has also improved, something Pam and Garrett attribute to Art Rooney II.

Whereas their time around the Steelers used to feel borderline embarrassing for what became of Mike, the family of one of the most important players in franchise history once again feels welcome.

"We've done a lot of healing," Pam said. "Art Rooney II has really made that possible. He's reached out to us, inviting us to games every year and making us feel like part of the team again."

Added Garrett: "I love Pittsburgh and all the wonderful thoughts everybody has about my dad. I rarely go a day where somebody doesn't say something wonderful and warm about my father."

It all feels appropriate, honestly.

The life of the Websters hasn't been pretty as our knowledge and understanding of CTE has grown. But how Pam, Garrett and the rest of the family has persevered has been tough and genuine, much like how Iron Mike played the game.

____

© 2025 the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Visit www.post-gazette.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments