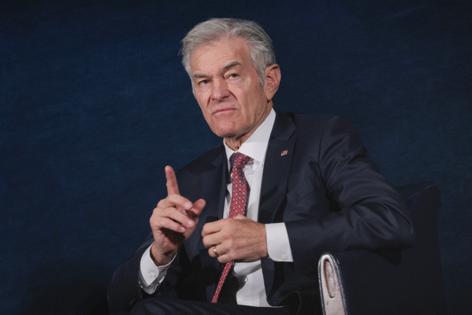

Commentary: Dr. Oz is not the retirement guru America needs

Published in Op Eds

Mehmet Oz is not an economist, but he occasionally plays one on TV. Speaking recently at a televised forum on mental health, the medical doctor and administrator for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services proposed an idea for how to boost the U.S. economy: Americans should just work longer. Adding a year of work would generate $3 trillion, he said, enough to “remove the [national] debt.”

Oz was careful not to suggest raising Social Security’s full retirement age, a longtime Republican policy now verboten in the populist era of the party. Mitt Romney favored raising it to 68 in his 2012 campaign for president, but by the 2024 campaign, Nikki Haley was excoriated for suggesting any increase at all. Oz simply encouraged Americans to work longer, instead of declaring that they must, and noted the health, tax and economic benefits for the country.

To the extent that this softer touch signifies the end of the retirement-age debate, it’s welcome. Social Security could be updated to reflect both the changes in life expectancy and the benefits of working longer, but raising the full retirement age — which is currently between 66 and 67 for most Americans currently working — is a poor way to do it.

To state the obvious, it’s a good thing that Americans are living longer. Over its 90-year history, the Social Security program has transformed retirement so that every American can look forward to a period of independent living after working. That period is longer with each generation.

Before Social Security, more than three-quarters of men over age 65 were working, in large part because just 5% of workers had a pension, despite life expectancy being just 61 years. Translation: Many Americans worked until they died. Now we not only live longer, but many of us can stop working in our older years. This is the luxury that Social Security purchased for all of us.

Yet this success has long been greeted with the tsking of fiscal conservatives, who have argued that an increase in life expectancy should be accompanied by an increase in the retirement age. It’s only fair, they say, and it’ll keep the system solvent.

It’s an argument with only selective empirical support. Social Security’s actuarial tables have shown for a century, for example, that women will live four years longer than men. Yet no one would suggest that women’s retirement age should be four years higher, or that a gap between white and Black Americans’ life expectancy should result in separate retirement ages by race. Or, when life expectancy fell in the pandemic, there were no calls from the “only fair” camp to lower the retirement age in response.

This gives the game away: Calls to increase the Social Security retirement age are driven less by logic than by a desire to cut benefits.

And it would most certainly be a benefit cut. Social Security can be claimed between the ages of 62 and 70. Claiming before age 67 results in a permanent penalty — a smaller monthly benefit for that person’s lifetime. Claiming after age 67 brings a similarly structured permanent bonus. Move 67 up to 68, or even 70, and there will be more penalties and fewer bonuses.

The debate over the retirement age also ignores the issue of fairness, which has less to do with life expectancy and more to do with work history. Consider two 18-year-olds, one who starts working immediately after high school and one who does not enter the workforce for 10 more years, after college and a graduate degree. From this perspective, the penalty/bonus system is particularly egregious. If the high-school graduate stops working at 62, they will be penalized after having worked 44 years; if the more educated one stops working at 67, they will be rewarded after having worked only 39 years.

There is a fix: Move to a flexible retirement age based on length of work history. This would result in higher benefits for the working class, who would no longer be penalized for claiming Social Security in their early 60s, and smaller bonuses for the educated elite, who would be expected not to claim benefits until their late 60s and early 70s, rather than be rewarded for it. Given that these two groups have as much as a four-year gap in life expectancy — and an even larger gap in retirement savings — it’s fair on that front, too.

A move to a flexible system has challenges: how should someone’s “work history” incorporate periods of unemployment, time spent caregiving, working during school, or midlife education, to name a few. But is it better to have a simple design with unfair implications, or a more complex system that improves fairness? Changing the unfair part requires also changing the simple part.

The debate over Social Security is dominated by its shrinking trust fund, which is expected to be depleted in seven years. No question, that problem needs to be addressed, though it may be less difficult than most politicians think. Whatever the solution, we should not lose sight of the larger purpose of the program: In the US, work earns the promise of lifetime economic security. Congress needs to do more than just keep Social Security solvent. It needs make sure the program keeps its promise to all working Americans.

____

This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Kathryn Anne Edwards is a labor economist, independent policy consultant and co-host of the Optimist Economy podcast.

©2026 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com/opinion. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments