Commentary: Deaths of Asian immigrants in ICE custody reveal a community under threat

Published in Op Eds

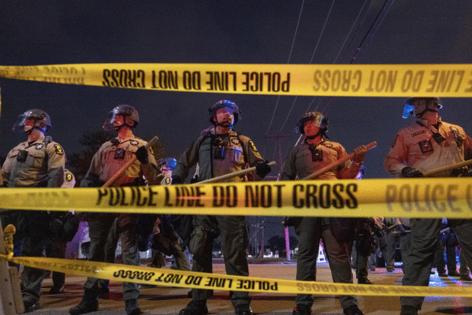

More than 30 people died while being detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement in 2025, marking it as the deadliest year for those held in custody by the agency in two decades. At least five of the detainees who died were Asian nationals: Chaofeng Ge, Nhon Ngoc Nguyen, Tien Xuan Phan, Kaiyin Wong and Huabing Xie. So far their deaths have received little public attention, even as ICE increases raids, expands capacity at its facilities and accelerates deportations across the country.

As I grieve these deaths, I’ve also witnessed ways that mass deportations have induced palpable fear throughout the Asian American community. Like the Hispanic and Latino communities, as well as other migrant groups across the U.S., Asian families live under constant threat of unlawful detentions, family separations, neglect, abuse and trauma at for-profit prisons.

In August, ICE guards found 32-year-old Chaofeng Ge hanging in a shower stall at the Moshannon Valley Processing Center in Philipsburg, Pennsylvania. Although investigators ruled Ge’s death a suicide, the autopsy report stated that he was found with his hands and feet tied behind his back. Despite these troubling circumstances, the federal government has yet to release the full records regarding Ge’s death to his family. Chaofeng’s brother filed a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit in November seeking transparency and accountability, and complained that the prison provided no Mandarin interpretation, leaving his brother isolated and possibly without access to medical care or mental healthcare while in custody.

Seven detainees at the California City Immigration Processing Center have made similar claims, accusing ICE of inhumane conditions inside its network of for-profit detention centers, including delayed medical care, inadequate food and water, and limited access to interpreters. Things are likely to only get worse unless the corporate profiteering that drives mass detention ends now.

Ge’s death points not only to the dangerous conditions inside ICE facilities, but also to the wider climate of terror that mass deportation policies have instilled in large segments of our community. Currently, 1 in 7 Asian immigrants living in the U.S. are undocumented and under imminent threat of removal, and undocumented Asian students represent a significant share of the population, accounting for approximately 16.5% of those eligible for DACA benefits.

Given the widespread and devastating impact of ICE arrests, more than 70% of Asian Americans now disapprove of President Trump’s immigration policies, arguing that his mass deportation practices have gone too far.

Trump’s policies are largely a continuation of immigration laws that have historically excluded Asian Americans. In the 19th century, our nation’s first mass deportation laws targeted the surveillance, registration and detention of Chinese people living in the American West. My family’s own immigration records from a century ago speak of my great-grand-uncle’s removal and of my grandparents’ detainment at the Angel Island Immigration Station in San Francisco.

Even though my grandfather was a native-born American citizen, his bride was imprisoned by armed guards for weeks because the government had racially profiled the two as illegal immigrants. White witnesses were required to testify on my grandfather’s birthright citizenship, and my grandmother was required to correctly answer a 56-question interrogation or else be deported. The poems of Chinese prisoners inscribed on the walls of the Angel Island immigration center speak to the fear and injustice that they and thousands more endured.

The use of deportations as a form of international segregation persists today as politicians rehearse old stereotypes to scapegoat and expel migrants. Once again charged as “criminal” and “invading armies,” a wide range of Asian groups face racialized deportation practices that deny them their rights and fracture families.

Consider Yunseo Chung, a 21-year-old Korean American student and lawful permanent U.S. resident. After she exercised her right to free speech while participating in student-led demonstrations at Columbia University, ICE moved to revoke Chung’s status and sought to deport her multiple times. Only when Chung sued the U.S. government to prevent her deportation did she gain a restraining order, blocking her removal.

Another innocent caught in this system is 6-year-old Yuanxin Zheng, a Chinese immigrant who arrived in New York City with his father in April. Even as they were following proper procedures to gain asylum, the family was forcibly separated by ICE on Nov. 26. Among the more than 2,600 children arrested this year by ICE, Yuanxin is one of the youngest. And although Yuanxin’s panic-stricken father was allowed a brief phone call with his son, he was left in the dark about his child’s whereabouts. ICE didn’t reunite the two until they were deported together, more than three weeks later.

Southeast Asian refugees also face a form of double jeopardy under the current administration’s policies. More than 15,000 Southeast Asians, many of whom served prison sentences for offenses committed in their youth, confront a second punishment: deportation orders.

For example, while serving 26 years in prison for murder, Phoeun You graduated from self-help programs, rebuilt his life and proved his commitment to change as he earned parole. Yet You never got to embrace his parents upon his release. Instead, he was immediately deported to Cambodia, a nation he never knew, and was permanently separated from his family. “I went from a life sentence to an eternal life sentence,” You told me when we spoke in February.

Last year, a survey by the Asian American Foundation reported that 63% of Asians now feel unsafe because of their race. ICE’s use of racial profiling and our nation’s xenophobic climate have undoubtedly contributed to these anxieties.

The five deaths of Asian nationals in ICE custody in 2025 are not just isolated tragedies. They reveal a system that has expanded faster than oversight can follow. Language barriers, delayed medical care and a lack of transparency inside detention centers have already had fatal consequences. This broken system does not make America safer but instead strikes fear throughout entire communities. ICE’s racial profiling and punitive enforcement practices do not bring about security but instead inflict lasting traumas on families and on generations like mine.

Ge’s passing demands justice — not only for his family, but for the end of for-profit prisons, of family separation and of the racist and violent enforcement of deportations. Each is a cruel and unusual punishment; together they constitute a morally bankrupt immigration system.

____

Russell Jeung is a professor of Asian American studies at San Francisco State University and co-founder of Stop AAPI Hate.

©2026 Los Angeles Times. Visit at latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments