Editorial: Florida gets 'the wrong guy' far too often

Published in Op Eds

There’s an officer in the Catholic Church colloquially known as the Devil’s Advocate. His duty, according to the Catholic Encyclopedia, is to make “all possible arguments, even at times seemingly slight” against candidates for sainthood. No canonization is legal without his input.

The church’s example is worth following by the criminal justice system — to prove innocence, not guilt.

Every detective bureau and prosecutor’s office should employ someone whose job is to argue in every case: “You’ve got the wrong guy.”

They get it wrong much too often. The National Registry of Exonerations lists 3,724 convicted people who were proved innocent eventually. Some of them had served most of their lives in prison.

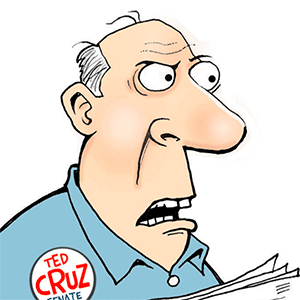

The saga of Sidney Holmes

Sidney Holmes of Pompano Beach was exonerated two years ago. Gov. Ron DeSantis signed a bill July 1 awarding him $1.7 million for the 34 years he served of a 400-year prison term for a convenience store robbery he did not commit.

He was a new 23-year-old father when he was arrested, and 57 when freed. “I missed 34 years of being a father to my son,” Holmes said.

Holmes was a victim of common fault lines in the justice system.

Mistaken witness identification from an improperly suggestive photo lineup convinced investigators and prosecutors that Holmes was the getaway driver in a robbery.

They overlooked a significant discrepancy between Holmes’ car and a similar Oldsmobile. The criminals’ car trunk had a hole in place of a lock; Holmes’ car didn’t. The state finessed that by assuming his car was repaired after the robbery.

‘Only’ 400 years

Once they convinced themselves they had the right suspect, it was over. Holmes wouldn’t name accomplices, because he couldn’t. The prosecutor asked the judge to give him 800 years but the judge reduced it to 400.

“The identification of Holmes was scientifically unreliable and contrary to modern-day best practices,” said Broward State Attorney Harold Pryor, whose office reinvestigated the case.

Sheriff’s deputies who did the original investigation “expressed shock that Holmes was sentenced to and had served so much time in prison,” Pryor said.

There have been 93 exonerees in Florida. Broward and Miami-Dade lead the state with 13 cases each in this dubious category.

Holmes was one of eight who had served 30 years or more. He and four other long-term prisoners were freed because state attorneys whose offices originally convicted them now have conviction review units to hear pleas from convicts who had exhausted their appeals in the courts.

Too few case reviews

Only five such units exist in Florida, according to the National Registry of Exonerations — in Broward, Hillsborough, Palm Beach, the Ninth Judicial Circuit (Orange and Osceola counties) and the Fourth (Duval, Nassau and Clay). That leaves 15 circuits with no mechanisms for righting such terrible wrongs. The Innocence Project of Florida, a voluntary group, is the only statewide resource.

After a conviction, the odds are extremely long against a successful appeal. Appellate courts aren’t concerned with guilt or innocence, only whether a trial followed procedural rules. All of the appellate rules are stacked in the state’s favor.

In a notorious case, the state Attorney General opposed DNA testing sought by a prisoner named Wilton Dedge and argued for the sake of “finality” that he should not have it, even if they knew he was innocent.

The test proved him innocent — another case in which an eyewitness ID was wrong. Dedge was released after 22 years of a life sentence. The Legislature gave him $2 million.

The best way to rectify such wrongs is to prevent them from happening.

‘A ton of work’ needed

To that end, a 2017 Florida law established “some, but not all” best practices for witness identifications, according to Seth Miller of The Innocence Project, which helped to clear Holmes. But the law still allows photo lineups and leaves enforcement to the discretion of trial judges.

“There is still a ton of work to be done to identify such cases and determine whether the suggestive photo lineup contributed to a wrongful conviction,” Miller said.

Other human factors contribute to wrongful imprisonment, and exculpatory DNA is not present in most cases. People with arrest records, as Holmes had, are typically prime suspects.

False confessions were found in 13% of exonerations. Nearly 30% involved false or misleading forensic evidence. Outright perjury or false accusations contributed to more than six of every 10 cases.

When mistakes are made, they tend to cascade. A trait known as confirmation bias can cause detectives and prosecutors to zero in on preferred suspects, ignoring evidence that might clear them.

This is why it’s to everyone’s advantage to have someone aggressively second-guessing every case before it goes to trial. No one should endure what happened to Sidney Holmes.

_____

©2025 Orlando Sentinel. Visit orlandosentinel.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments