Editorial: The student lending mess needs to be fixed

Published in Op Eds

After years of poor decision-making, the federal government’s $1.64 trillion student loan program is in critical condition. Congress needs to stanch the bleeding — and give serious thought to overhauling this flawed system for the longer term.

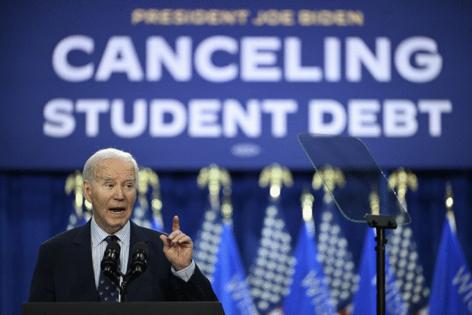

The underlying problem is clear: Too many students have loans they can’t repay. Even before the pandemic, about 17% of borrowers were delinquent or in default. COVID-related payment freezes and an ill-advised effort by President Joe Biden’s administration to offer debt forgiveness have exacerbated the problem, leaving millions of borrowers in legal limbo and fewer than half current on their payments.

The new administration isn’t helping. Halving the Education Department — or even eliminating it — might make sense in the long run, but right now it’s making matters worse: Among other things, staff are needed to answer questions from loan servicers and manage debt collections after contracts with private agencies were terminated in 2021.

Congress, which forced Biden to restart student loan payments in 2023, needs to step up again to ensure the government has the capacity to handle existing debt. Instead of waiting for court battles to play out, lawmakers should end Biden’s debt forgiveness efforts entirely, then address a chronic complaint: How do you reform a lending program that costs taxpayers billions of dollars and leaves millions of delinquent borrowers with impaired credit scores?

As a start, simplifying loan options would help. Instead of the seven repayment plans now on offer, students should pick between two: 10 years of monthly payments or 10% of income for as long as it takes. Forgiveness should be off the table except in clearly defined cases of hardship. And students should be able to know their tuition costs for the next four years, free of surprise hikes; colleges, for their part, should have to budget accordingly.

More fundamentally, lawmakers should consider ways to apply some basic underwriting discipline to a program that often extends federal loans for dubious degrees. Previous efforts to make such lending contingent on outcomes were based on default rates that were easily manipulated or were applied primarily to for-profit schools.

A better approach would focus on labor-market value. As one example, loans could be offered only for programs that can show that a reasonable percentage of graduates — half, say — earn a salary higher than the median high school graduate or bachelor’s degree recipient. (A Republican plan introduced during the last Congress was on the right track.)

Restricting federal loans in this way would encourage schools to shift their curricula to favor more marketable skills. That shouldn’t mean the end of liberal-arts education; students would still be able to major in ancient Greek or social work. But for an education system struggling to produce graduates with in-demand aptitudes — and which encourages far too many students to take on debt for not-so-useful degrees — it should lead to a salutary change in emphasis.

There are plenty of other reasonable proposals for rethinking this system. The goal isn’t to create a lending program free of delinquencies or defaults; that’s unrealistic. But a delinquency rate closer to that on other types of unsecured loans, such as credit cards, would be a plausible ambition, and a sign that money is being allocated more rationally.

Fixing the current student loan mess should be job No. 1. But Congress should also be thinking about how to build a saner and more productive system of higher education for the future — one that could provide benefits for generations to come.

_____

The Editorial Board publishes the views of the editors across a range of national and global affairs.

_____

©2025 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com/opinion. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments