Commentary: The US should learn from the Korean War when negotiating with Ukraine

Published in Op Eds

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s recent contentious meeting with President Donald Trump raised eyebrows among many Americans. Vice President JD Vance called the Ukrainian president “disrespectful,” but the circumstances of the meeting in the Oval Office were not unusual in diplomatic history.

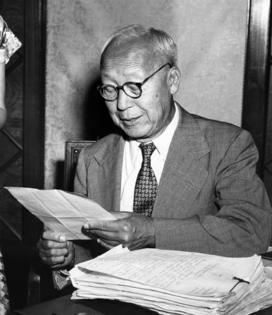

When Dwight Eisenhower took office intending to end the Korean War quickly, he found himself at odds with then-South Korean President Syngman Rhee.

Elected in November 1952, Eisenhower promised a swift conclusion to the conflict, whereas Rhee opposed this approach, advocating for the reunification of North and South Korea by force. Rhee insisted on securing a mutual defense treaty with the U.S. if his military plans could not be implemented.

Eisenhower faced significant challenges in negotiating the armistice agreement, which took seven months. He assumed office Jan. 20, 1953, and the ceasefire deal was signed on July 27. During this period, Rhee proved to be a major obstacle for Eisenhower.

Concerned that Rhee might sabotage the negotiations, Eisenhower considered three options: overthrowing the “often unreliable ally” (Rhee), negotiating a bilateral security pact with South Korea or withdrawing U.S. troops.

The first option, known as Operation Ever-ready, received serious consideration from U.S. officials in mid-1953 as a potential solution to Rhee’s objections to parts of the proposed armistice agreement. However, this option was never put into action.

Eisenhower recognized that Rhee preferred the second option — negotiating a bilateral security pact with the U.S.— to deter potential attacks from the North following the ceasefire.

The third option, pulling out American troops, was impractical for the U.S., as substantial military resources had already been committed since the beginning of the war. Withdrawing American soldiers and potentially losing to communism would have been more damaging for the U.S. than for South Korea.

At that time, South Koreans constituted about 60% of United Nations troops. Rhee even threatened to withdraw South Korean forces from the U.N. coalitions to undermine America’s efforts toward a truce agreement.

To pressure Eisenhower, Rhee released anti-communist prisoners of war without consulting the U.S. These anti-communist POWs were individuals conscripted by the communist North after the war began, who had since expressed their loyalty to the democratic South. Upon the ceasefire, the North demanded their return, asserting they belonged to their military; the South objected on humanitarian and political grounds.

Rhee’s release of these anti-communist POWs was a major event that could have derailed the armistice negotiations. Eisenhower was taken aback.

The POWs event prompted Eisenhower to seriously consider the second option of establishing a mutual defense treaty with South Korea. He sent his assistant secretary of state, Walter Robertson, as a special envoy to South Korea. In the end, the two leaders reached an agreement to secure an armistice in exchange for the U.S.-South Korea Mutual Defense Treaty and economic assistance. The armistice agreement was signed on July 27, 1953, followed by the U.S.-South Korea Mutual Defense Treaty on Oct. 1, 1953.

Despite this, the rift between Eisenhower and Rhee was not resolved after the signing of the Mutual Defense Treaty. On July 30, 1954, the two presidents met at the White House. Eisenhower urged Rhee to establish normal diplomatic relations with Japan. Rhee refused, citing that Japan had justified its brutal 36-year colonial rule over Korea in the name of industrialization. Eisenhower countered that the past should be left behind and that both countries needed to move forward. Rhee said that would not happen in his lifetime.

Eisenhower became so furious that he abruptly left the meeting. When he returned shortly after, Rhee quickly stood up and exited the room.

Astonishingly, just four months later, Eisenhower granted Rhee’s wish. Rhee was thrilled to see the U.S.-South Korea Mutual Defense Treaty take effect and secured aid from the U.S.

Eisenhower’s humanitarian diplomacy, which prioritized the interests of vulnerable Koreans, ultimately proved effective.

In 1965, when President Lyndon Johnson requested Park Chung-hee to deploy South Korean troops to Vietnam, the South Korean president agreed to his request.

Over the course of eight years, from 1965 to 1973, about 300,000 South Korean soldiers, averaging around 50,000 each year, fought alongside U.S. forces in the Vietnam War, conducting 563,387 military operations. More than 5,000 South Korean soldiers were killed in action, with more than 10,000 wounded.

It is time for Trump to reflect on the complex and nuanced nature of international diplomacy.

The potential agreement between Trump and Zelenskyy could be even more beneficial than that of Eisenhower and Rhee. This is because Ukraine has significant deposits of natural resources, such as titanium, graphite, lithium and uranium, which are vital for America’s national security. In contrast, South Korea did not provide such an abundance of valuable minerals.

Trump could establish a mutual defense agreement with Zelenskyy. This would not be an unreasonable proposition, considering the U.S. already pledged a security guarantee to Ukraine upon its return of all nuclear warheads to Russia by 1996, based on the Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurances.

After an armistice, Trump might reconsider his stance, which is not uncommon in international relations. For instance, Jimmy Carter as president unilaterally annulled the Mutual Defense Treaty between the U.S. and Taiwan. This treaty was designed to protect Taiwan from invasion by China but was terminated on Jan. 1, 1980, just one year after the U.S. established diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China.

Moreover, numerous scholars observe that military alliances are not always upheld during war. In a worst-case scenario, Washington might choose to overlook a mutual defense agreement with Zelenskyy, though I hope that will not happen.

____

Seung-Whan Choi teaches Korean politics and international relations at the University of Illinois Chicago. A retired Army officer, he is the author of four books and 60 journal articles.

___

©2025 Chicago Tribune. Visit at chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments