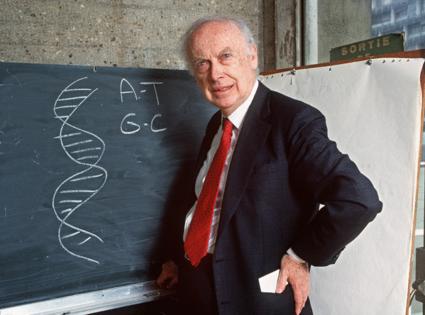

James Watson, who helped discover DNA structure, dies at 97

Published in Science & Technology News

James Watson, whose co-discovery of DNA’s structure brought genetics to the forefront of scientific research before his remarks about the intelligence of Black people caused public outrage, has died. He was 97.

He died on Nov. 6 in East Northport on New York’s Long Island, The New York Times reported. Citing his son, Duncan, the Times said Watson had been transferred to a hospice this week from a hospital where he had been treated for an infection.

As a 24-year-old zoologist, Watson joined Cambridge University researcher Francis Crick in proposing the “double helix” configuration for deoxyribonucleic acid, which holds the genetic information allowing hereditary qualities to pass to the next generation of humans and other organisms. The breakthrough in 1953 built on Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution by explaining the mechanics of heredity in the origin of species.

“In my mind, Darwin was the most important person who ever lived on Earth,” Watson told Charlie Rose in a 2005 interview.

The discovery of the twisted-ladder shape with a sugary phosphate backbone and nitrogen “rungs,” or bases, made it possible later on to manipulate genes, track inherited diseases and use genetic analysis to solve crimes. Watson unraveled the code of the four constituent bases — adenine, thymine, guanine and cytosine — which combine in pairs to make up DNA’s shape and allow replication.

Genetic sequencing enabled U.S. biologist J. Craig Venter to announce in 2010 that his team of scientists had made a copy of a bacterium’s entire genome and then transplanted it into a related organism, raising hopes for everything from future vaccines to new biofuels. DNA coding led molecular pathologists in 2005 to pinpoint birds as the source of the influenza epidemic that killed at least 50 million people in 1918. The science also helped identify the remains of the Russian tsar’s family more than seven decades after their execution in 1918.

“Practically all the scientific disciplines in the life sciences have felt the great impact of your discovery,” Professor A. Engstrom said in presenting Watson, Crick and Maurice Wilkins with the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1962.

Wilkins had provided experimental evidence using X-ray diffraction. Rosalind Franklin, an English biophysicist at King’s College London whose X-ray results and unpublished research were used by Crick and Watson, died in 1958.

Disparaging Comments

Watson drew condemnation later in life for disparaging comments about women, Black people, homosexuals and the obese. He was criticized as sexist for downplaying the role of Watson in the DNA discovery.

In 2014, he said he would sell his Nobel Prize medallion as his controversial remarks had made him an outcast in the scientific community. Watson also said he needed the money and would donate some of the proceeds to scientific research. The medal sold at auction for $4.8 million.

“Because I was an ‘unperson’ I was fired from the boards of companies, so I have no income, apart from my academic income,” he said, according to the Financial Times.

The medal’s buyer was Alisher Usmanov, a Russian billionaire who later returned the medal to acknowledge the American biologist’s contribution to science.

James Dewey Watson was born on April 6, 1928, in Chicago. He won a scholarship from the University of Chicago and graduated with a zoology degree in 1947 at age 19. He received a doctorate from Indiana University three years later.

“Until one has cleared high school, there is little to be gained by questioning what your teacher wants you to learn,” he said in the 2007 book "Avoid Boring People: Lessons From a Life in Science." “Save flights of rebellion for when authority does not have you by the throat.”

‘Secret of Life’

He spent a year in Copenhagen as a postdoctoral fellow before attending a symposium in Naples in 1953, where he saw Wilkins’s X-ray diffraction results using crystalline DNA. Watson then focused on nucleic acids and proteins, working at Cambridge University’s Cavendish Laboratory, where he joined forces with Crick to solve the problem of DNA’s structure.

On Feb. 28, 1953, Crick announced at the Eagle pub in Cambridge, England, that they had just “found the secret of life.” Earlier that day, the two had uncovered the self-replicating double helix.

“This structure has novel features which are of considerable biological interest,” Watson and Crick wrote in an April 1953 letter to Nature. It was widely regarded as one of the biggest understatements in science. Crick and Wilkins both died in 2004.

Watson’s 1969 account of the discovery was published under the title "The Double Helix" and was criticized for his treatment of Franklin and for revelations about the selfish motives of scientists.

Watson joined the biology department at Harvard University, where he became a professor in 1961. He resigned in 1976 to work as director of the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York, a center for biomedical research and education. He was the center’s president from 1994 to 2003, when he became chancellor, according to the laboratory’s website.

He served as director of the National Center for Human Genome Research at the National Institutes of Health from 1989 to 1992. He spearheaded the effort to chart the genetic code of the human species so that tests and possible cures could be developed for inherited diseases.

Watson was strongly criticized in 2007 over comments he made in London’s Sunday Times about the intelligence of Black people, implying they were genetically inferior.

Public Outcry

“All our social policies are based on the fact that their intelligence is the same as ours — whereas all the testing says not really,” he was quoted as saying. While he hoped that everyone was equal, “people who have to deal with Black employees find this not true.”

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory suspended Watson from his position as chancellor, and a book tour of the United Kingdom was canceled. Watson announced his retirement from his duties at Cold Spring the following week.

“I am mortified about what has happened,” he said in response to the public outcry. “More importantly, I cannot understand how I could have said what I am quoted as having said. I can certainly understand why people, reading those words, have reacted in the ways they have.” He added: “There is no scientific basis for such a belief.”

The laboratory stripped him of his titles in 2019 after further comments about race and intelligence.

Watson was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1977, held honorary degrees from more than a dozen universities and was a member of the National Academy of Sciences.

He was married to Elizabeth Lewis, with whom he had two sons: Rufus and Duncan.

©2025 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments