What we lose when our leaders choose to tear down what connects and nourishes us

Published in Lifestyles

The day after President Donald Trump’s administration began demolishing the East Wing of the White House to make way for a massive 90,000-square-foot ballroom, I sat in a room full of people witnessing what happens when we build, rather than tear down.

Structures. Communities. People. Imaginations.

The Chicago Public Library Foundation held its annual awards ceremony at the University of Illinois-Chicago Pavilion on Tuesday night. Former Chicago Public Library Commissioner Mary Dempsey received a civic leadership award. Pulitzer Prize-winning author Percival Everett won the Carl Sandburg Literary Award and joined NPR host Scott Simon in conversation on stage.

Calumet City poet José Olivarez won the 21st Century Award, which honors an early career author with ties to Chicago. Past winners include Cristina Henríquez, Rebecca Makkai and Shermann "Dilla" Thomas. Nate Marshall, winner of the same award in 2020, introduced Olivarez.

Olivarez is no stranger to accolades. He won the 2018 Chicago Review of Books Poetry Prize. His debut book of poems, “Citizen Illegal,” was a finalist for the PEN/Jean Stein Book Award. His most recent collection, “Promises of Gold,” was long-listed for a National Book Award. In 2019, he received a Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Poetry Fellowship from the Poetry Foundation.

This one hit different.

“I lost my mind,” Olivarez told the Chicago Tribune’s Darcel Rockett a few days before the ceremony. “For me, this is the most meaningful award that I’ve received.”

Olivarez is the son of Mexican immigrants.

“Growing up,” he told Rockett, “my parents were undocumented for a long time, and a lot of what I write about is what it means to be living in the United States and not have the full protection of the state that one might expect here.”

On Tuesday night, after accepting his award, Olivarez talked about growing up in south suburban Calumet City. He talked about feeling like he and his family were a problem to be solved — at the post office, at the grocery store, at the local school where his mom tried to register him but they were turned away because he didn’t speak English.

He talked about the one place that always made his family feel welcome.

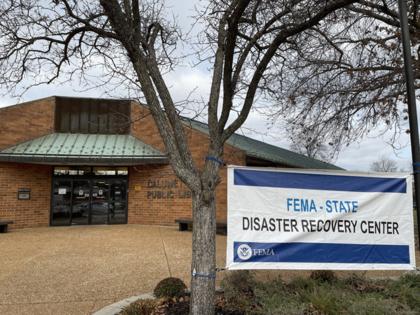

“That was the Calumet City Public Library,” he said.

“The only time I ever felt nervous in the library was when I had to check out books in the library,” he said. “I always picked out more books than the lending limit allowed. So the librarians always asked me, ‘Are you sure you’re going to read all those books in two weeks?’ The answer was always yes. I’d stack the books on my dresser and work my way through them one by one until I finished them all.”

He loved anything by Walter Dean Myers.

“Reading his books felt like reading about my own neighborhood and friends,” Olivarez said. “Myers’ books made me want to run outside and play basketball. And they made me want to stay inside and finish reading.”

He loved “The Boxcar Children” books.

“The library was luxurious,” he went on. “It was the only place in my young life where I could choose whatever I wanted and not worry about the price. Everything was free. I don’t know where my life would be without the library.”

Fortunately, he said, he doesn’t have to dwell on that alternate reality.

“There are some alternate realities I do need to imagine,” he said. “Those realities begin with what I learned all those years ago at the Calumet City Public Library. What might our country look like if there were more spaces that felt as free and safe and welcoming as the library?”

Indeed.

And what will our country look like if we continue this path of wreckage — to historic landmarks, to national parks, to museums, to libraries? To institutions that belong to all people, that welcome all people, that see worth and promise and humanity in all people?

What will our country strive for and stand for? What do we hold sacred?

Olivarez went on to graduate from Harvard University. The kid who was turned away from preschool. The kid who found a way to fill his head and his world with words anyway. The kid who found refuge and magic in a library. Now he fills the world with his own words.

In her interview with Olivarez, Rockett asked him about his poem called “Mexican Heaven.”

“I wanted to find a way to write about immigration in the United States, but I didn’t want to do it straightforwardly,” Olivarez told her. “One day, it hit me, ‘What’s another place that promises to be perfect when you get there, but there are gates and there’s someone holding a list to check to see if your name is on it?’ That classical interpretation of heaven also has a border.

“I love the idea that Jesus, Lord and Savior, gets reborn in the palms every day as Jesus, who’s just your cousin from down the street, and he’s got a big back tattoo,” he continued. “To me, it makes sense. Why shouldn’t we treat each other as though we have that kind of holiness and special features about us? Why shouldn’t we treat each other like we are all the children of God?”

And what could happen if we did?

©2025 Tribune News Service. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments