When human bones turn up in South Florida, this professor and her students get the call

Published in Lifestyles

FORT LAUDERDALE, Fla. -- The discovery of what appeared to be a human femur and pelvic bone might have unnerved the construction workers who unearthed them near Lake Worth Beach last week, but for Dr. Heather Walsh-Haney and her students, it was just an average Monday.

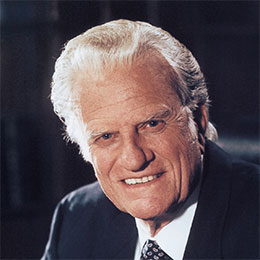

The forensic anthropologist and Florida Gulf Coast University professor is often one of the first calls officials make when they need to solve the mysteries of Florida’s dead. She travels the state with her team of staff and students, working about 200 cases a year alongside police and medical examiners, from human remains discoveries like Monday’s to mass-casualty events and cold cases including the Surfside condo collapse, Hurricane Irma, the death of Brian Laundrie and the high-profile disappearance of 8-year-old Christy Luna, who disappeared over 40 years ago and has never been found. Beyond Florida, Walsh-Haney has investigated historic tragedies throughout the world, including the Sept. 11 attacks, the Tulsa race massacre and femicides throughout Latin America.

“I’ve pretty much dedicated my life to anthropology,” the professor explained to the South Florida Sun Sentinel after returning from a series of expeditions, including the one in Lake Worth Beach, which she could not discuss in detail due to the active investigation.

Deputies had “immediately” notified FGCU after uncovering the bones, Palm Beach County Sheriff’s Office spokeswoman Teri Barbera had said in a news release. Walsh-Haney’s team continued scouring the site for additional remains Tuesday and Wednesday last week. By Thursday, all of the bones had been taken to the medical examiner, Barbera said, though she provided few details as to whom the bones might belong and whether they could help solve any existing cold cases.

Bones are Walsh-Haney’s bread and butter. She measures, scans, and X-rays skeletal remains to reconstruct who they were in life as well as — perhaps most critically — the moments leading up to their death. Officials primarily rely on Walsh-Haney when investigations involve badly decomposed or skeletal remains, services badly needed in the South Florida heat.

“In Florida, the decomposition process happens immediately,” Walsh-Haney said. “We have elements of remains decomposing in a matter of days, not weeks.” When decomposition is so advanced that medical examiners cannot determine the body’s sex or ancestry, “they call me in.”

As soon as she gets the call, Walsh-Haney heads out with her team, composed of staff members, graduate students, and a few “well-trained” undergraduates. They have their own crime scene truck, so “I can be wheels up with my team in two hours, if they discover there’s a need,” she explained.

Then they set to work, first to recover any additional remains, then to examine them in the medical examiner’s office. Walsh-Haney emphasized that medical examiners don’t require her services, but having an anthropologist on hand can help them answer questions more quickly and with greater depth — such as whether remains belong to a human or an animal, or what skeletal material, like teeth, is most likely to yield DNA, which can later be used for cutting-edge investigative techniques like genetic genealogy.

Once Walsh-Haney constructs a picture approximating how a person may have looked, law enforcement can use it to query missing persons databases in hopes of identifying them. She also helps law enforcement determine what traumas the person might have suffered and whether those traumas occurred before the time of death, during or after it.

Identifying any trauma that took place around the time of death is “where things become even more important,” Walsh-Haney explained. In one recent case, she examined hundreds of bone fragments to determine that an Orlando man had likely shot a woman he was dating before dismembering, burning and burying her remains.

Growing up, Walsh-Haney always wanted to work with the military or law enforcement in some capacity. Her grandfather, Walter Walsh, was a prominent FBI agent, and her own father followed in his footsteps. Meanwhile, Walsh-Haney and her mother both loved museums and history. In college, Walsh-Haney discovered that forensic anthropology merge those interests.

She has now taught at FGCU for over 21 years; many of her students have gone on to work at Florida’s medical examiner’s offices and law enforcement agencies. Several of her colleagues also consult on human remains cases throughout the state, but Walsh-Haney’s relative proximity to South Florida makes her one of the region’s most called-upon experts.

Medical examiners in Palm Beach, Broward and Miami-Dade counties frequently seek her help, though she visits Duval County in the northeast corner of the state most often, given its high murder rate.

The work comes in bursts of activity. Sometimes, like last week, Walsh-Haney and her team find themselves traveling across the state from one site to the next.

“Everything happens at once,” she explained. “Then, stasis.”

Duty — and bones — call. By next week, she’ll be off to another assignment.

©2025 South Florida Sun Sentinel. Visit at sun-sentinel.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments