Residents want KC's Black mecca, once a vibrant neighborhood, brought back to life

Published in Lifestyles

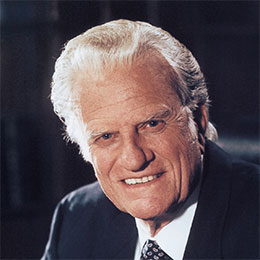

KANSAS CITY, Mo. — As anti-violence activist, Alvin Brooks, entered Pilgrims Rest Missionary Baptist Church, memories from his many years spent growing up in this Kansas City house of worship flooded his mind.

The old stone building located in the heart of the Dunbar neighborhood was the site for baptisms, Easter services, and gatherings that took place during the community leader’s youth. Brooks, 92, spent his childhood in the closely knit Dunbar neighborhood and watched it rise from a poor community to one of significant importance to Black culture in Kansas City.

Across the street from his childhood church stands the decaying remains of Scott Grocery Store, where Brooks worked as a teenager. The two landmarks and a park are all that’s left of a once-thriving community that stood as a testament to Black self-reliance and commerce.

“I still come down to drive through the area often,” said Brooks. “I start getting all these memories of how everything used to be and all the people who lived in the area.”

For many young people in Kansas City, Dunbar’s storied past remains largely unknown. But now a dedicated group of advocates for the preservation of Dunbar history and organizations, including the Heart of the City Neighborhood Association and the Kansas City Museum, are working to tell the story of the Dunbar community and restore what’s left of its historic structures.

The once vibrant, Dunbar — referred to at one point in its history as Kansas City’s Black mecca — has long been neglected and now lies in decline. It’s marked by vacant lots, a scattering of old deteriorating houses, and holds no hint of the thriving community that once resided there.

According to the 1920 census the all Black Dunbar community was home to over 300 residents. Today, more than 100 years later, that number is only at 597 with 67% being Black and 34% Hispanic. Only 26% of the community live in owner-occupied housing and almost a quarter of the housing units there are unoccupied, according to a study done by The Heart of the City Neighborhood Association.

With gentrification steadily transforming predominantly Black neighborhoods on the city’s Eastside such as Ivanhoe and Beacon Hill, residents of Dunbar worry the history of their advantageously located neighborhood, just west of the Truman Sports complex, could eventually be lost to development.

“I didn’t intend on finding or being connected to Dunbar,” said Damon Lee Patterson, a Kansas City photographer. “I was looking for land in the area for maybe a community garden and wanted to find a place where there wasn’t any action and had potential.”

Unbeknownest to Patterson, the Dunbar area he identified as a potential community garden site had, back in the mid 1920s, been called a gardening center with more than a dozen greenhouses producing nearly 90% of the flowers sold in Kansas City.

Patterson began reaching out to local property owners in the Dunbar neighborhood, gradually uncovering its history. He heard numerous stories from former residents who still owned land there, many of whom were reluctant to sell due to the sentimental value they placed on it.

Through these conversations, Patterson began to piece together the story of one of Kansas City’s most overlooked historical gems.

“I started learning how many of these lots have been in the hands of the same families that lived here, I wasn’t able to get what I wanted for the community garden but I started doing more research,” he said.

The history of Dunbar spans more than a century. It began in 1889 with the purchase of rural farmland, which was later transformed into a predominantly white industrial area.

Forming Dunbar

Around 1915, Black residents, facing limited opportunities for land ownership elsewhere around Kansas City, began buying lots in the area, which was then a commercial, industrial and residential district just outside the city known as Leeds.

At the time of the early 20th century Black Kansas City residents were subjected to racially based housing discrimination more commonly known as “redlining,” preventing them from moving west of Troost Avenue. Many of those racially discriminating practices continued in Kansas City long after the Fair Housing Act of 1968 forbid them.

Eventually, the predominately white Leeds community began to move westward leaving that area open for new residents. Those residents were Black. The neighborhood became Kansas City’s first Black suburb.

According to Brooks, the area, including the side where white residents lived and the area where Black residents lived, began to be known as Leeds-Dunbar, before Black residents finally dropping the Leeds name. The area where Black families lived was named after the renowned African American poet Paul Laurence Dunbar, who passed away in 1906.

The residents began to establish its own infrastructure, opening its first school, the Dunbar School, in 1917, followed by the creation of Liberty Park (now the Yvonne Starks Wilson Park) in 1921.

Brooks’ family moved into the area in 1933 when he was an infant. His family had fled North Little Rock, Arkansas to Kansas City after his father, a moonshiner, was chased out of town by law enforcement, for killing a white man over a moonshine business conflict.

Brooks recalls that despite the hardships the community faced—such as having only one paved road on 35th Street and no indoor plumbing—the sense of unity and strength among residents in the neighborhood was strong.

“You hear people talk about a village nowadays but Dunbar really was that,” said Brooks. “We were poor but one thing we did do was share everything we had. Anything we needed we could get from someone in my community.”

Brooks sold goat’s milk.

The story is that as an infant, Brooks couldn’t tolerate cow’s milk and was suffering with malnutrition. To safe his life, his father bought a goat for its milk. As Brooks grew older, he remembered how his family, along with many others in the community, relied on commerce and bartering to ensure everyone had what they needed.

It was common, Brooks said, for residents to keep their own livestock. His father raised rabbits, chickens, and, of course, goats.

“We ended up with five or six goats and I sold goats milk at age 9 and was the only person in community selling goats milk,” he said.

When the local milk man learned young Brooks was selling goat’’s milk, he gave the boy about a dozen bottles. Brooks rose early mornings filled his bottles and delivered them on his milk route. To his surprise he began to get orders from the neighboring white community of Leeds, just across the Blue River that ran south of Dunbar.

The first generation of Black residents in Dunbar laid the groundwork for the neighborhood’s reputation for self-reliance and community-driven commerce. Over time, the area earned the nickname “The Garden of Eden” among its residents, thanks to the abundant resources available to them.

After World War II, the neighborhood experienced a period of economic growth as many Black residents secured jobs in manufacturing. This led to the rise of a middle-class community, which allowed the area to thrive and expand as the more Black families moved to the area.

As time went on several grocery stores opened, many of which stocked goods produced by the residents themselves.

The building at 3400 Hardesty Ave. was once a grocery store and boarding house owned by Oscar Scott. Today, it stands as one of the few remnants of the Black-owned businesses that fueled the community’s growth and success.

During his teenage years, Brooks became close friends with the Scott family.

“We had about three or four grocery stores and I worked at Mr. Scott’s store when I turned 15 because he and my father used to slaughter hogs together,” said Brooks.

In the 1970s, Rose Calmes purchased the former grocery store boarding house building and transformed it into a restaurant and convenience store. That’s gone now too.

Saving history

Today the 125-year-old former grocery is part of a restoration initiative led by The Heart of the City Neighborhood Association, aimed at preserving the site and securing its designation as a historical landmark.

Katheryn Persley’s family lived in Dunbar and as president of the neighborhood association says the project is crucial to preserving and sharing the story of Black Kansas City.

“That building was built before that area was a part of Kansas City,” said Persley. “From a historical aspect we want to preserve it because of its significance not just to the Black community but to all of the city.”

For the past five years, the organization has been working to raise funds to restore the old building. It is unknown how much a full restoration would be, but they are hoping to raise at lease the $9,300 to pay the delinquent taxes on the building.

What began as a Heart of the City Neighborhood Association plan to restore the old grocery store has since grown into a multifaceted project, now involving collaborations with several other organizations, including the Museum of Kansas City, the University of Kansas City Center for Neighborhoods, and Creative Center KC to document the Dunbar story.

Additionally, Patterson — that’s the photographer — will be leading a multimedia project, interviewing former residents to share their personal accounts of life in the area.

“We need to collect these stories of what life was like for residents back then while we can because this is history that tells the story about how people were able to support and look out for each other in this close-knit community,” Persley said.

The Museum of Kansas City at 3218 Gladstone Blvd, is developing an exhibit to honor the history and legacy of the Dunbar community. Scheduled to open in late 2025 or early 2026, this exhibit will be the first in a series aimed at exploring the rich histories of Kansas City’s neighborhoods.

“We want those who visit the exhibit to learn how they can be more involved in the neighborhood,” said Anne-Marie Turtula, director and CEO for the museum. “We are going to look at community values, businesses, home life, entertainment, recreation, politics, activism, historic sites in Dunbar, maps and how it has changed.”

By the 1970s, residents began moving out of Dunbar. Relaxed housing regulations allowed Black residents to move into other areas. Dunbar lost civic leaders who had been the pillars within the neighborhood.

Then a series of tragic happenings hit the community, including a tornado, a flood, and the closure of local factories. More residents left.

“You began to see a lot of people jump at the opportunity to live in places that were closed off to them after de-segregation,” said Patterson. “I think that story is one that is very common in America because it happened to a few prominent Black communities across the nation.”

By the 1980s, the neighborhood that was once a symbol of hope and prosperity for Black Kansas City had deteriorated due to neglect, rising crime, and dwindling resources.

Owen Lane, a former resident, recalls witnessing the dramatic shift.

“I grew up hearing stories, I wouldn’t call them the glory days but they always talked about how we stuck together,” said Lane, 46. “I can remember as a kid just knowing what felt like just about everybody. But things took a turn and people started to leave.”

Last November, Lane joined other former residents of Dunbar to review conceptual designs for some improvements developed by University of Kansas students. Four student teams are composed of those studying architecture, urban planning and design, focused on various locations within the Dunbar boundaries, working to create plans for revitalizing the community.

The students, who were initially unfamiliar with the Dunbar neighborhood, had the opportunity to learn its history. The students engaged with residents, gaining insights into what the community’s former inhabitants hoped to see in a revitalized Dunbar.

“This was a 14-week effort to create the projects and present designs,” said Avery Neer, a graduate teaching assistant for KU. “They got to learn about terrain of the area so we have groups developing things like a pollinator garden, another working on a community garden and one group has a design for the runoff for flood waters. They really capitalized on the many possibilities.”

Former residents who gathered for the unveiling of the Dunbar designs expressed hope about what might be accomplished through a collective community effort.

Pamela Nicolson-Collins, a lifelong Kansas City resident who grew up in the neighborhood before joining the military, was among them.

“Growing up here made you proud and I don’t have any bad memories,” said Nicholson-Collins. “Things were safe, we walked everywhere, we had our own stores, people with gardens who grew food. This area got stuck and we need something new to change it or we will lose it.”

Both Lane and Nicholson-Collins emphasized the importance of the community taking charge of rebuilding the area rather than waiting for developers to do so. They believe that once the families who still own land in Dunbar sell it, the neighborhood’s history will be lost in the name of progress.

Patterson is optimistic that, in the coming years, the story of Dunbar will reach residents like himself, who were unaware of the area’s historical importance. He aims to keep gathering stories from former residents to highlight a time when Black community members united to challenge an unjust and biased housing system, develop their own neighborhood and ultimately creating a lasting legacy.

“There is such a rich beautiful history that nobody knows about,” said Patterson. “We don’t want this culturally significant location to lose its identity so we need to inspire people to invest in a re-imagined Dunbar.”

©2025 The Kansas City Star. Visit at kansascity.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments