The economy is dragging, but the stock market is thriving. Why?

Published in Business News

From jobs to housing to grocery prices, the U.S. economy has been weakening for months.

But the stock market is telling a different story, thanks to a handful of companies called the Magnificent 7: Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Alphabet, Meta, Nvidia and Tesla.

These tech giants — which deal in everything from e-commerce to software to chip manufacturing — comprise a disproportionate share of the market and have pushed it to record highs in the AI boom.

Without spending by the Mag 7 and other tech companies, the U.S. economy “would have barely grown” in the first half of the year, Oxford Economics lead economist Adam Slater wrote in an Oct. 3 research briefing.

In other words, tech is helping keep the economy afloat. But if these companies’ fortunes change, the downstream impact could be severe.

Though economists aren’t forecasting an AI crash, they have acknowledged similarities between the AI boom and previous bubbles, from the dot-com bust of the early 2000s to the ultimately catastrophic bull market of the 1920s.

The fear is, if trillions of dollars in projected spending on AI infrastructure fail to generate revenue, there is potential for a downturn with global ramifications.

The Mag 7 for years have exceeded the rest of the S&P 500, the index that tracks the stock performance of the leading 500 public companies. The gap started widening after OpenAI released ChatGPT in 2022, launching the AI boom.

The impact of the Mag 7 on the markets is clear when those companies are out of the picture. Between January 2020 and Nov. 14 of this year, the S&P 500 outperformed the S&P 493 (the index minus the Mag 7) by a median annual return of nearly 8 percentage points, according to analysis from Piper Sandler Technical Research.

The bull market has been good news for high-income Americans, who tend to hold more stocks than the average consumer and so benefit more from rising stock prices. Those high-earners also tend to keep spending when economic headwinds cause lower-income consumers to pull back.

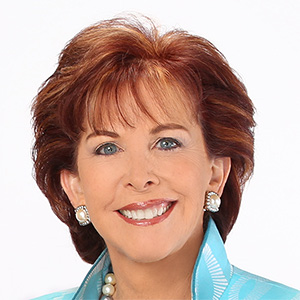

Higher-income earners are driving about half of U.S. consumer spending, said Anthony Saglimbene, vice president and chief market strategist at Ameriprise Financial.

“With the market up right now, one of the things that we’ve been talking about is, markets and the economy stand on pretty narrow pillars, or at least they have so far this year,” he said.

The University of Michigan Surveys of Consumers reported in October the economic sentiment of stockholders, especially those with the biggest portfolios, has improved since May. Sentiment of nonstockholders has declined in that time, landing where it was in 2022 when post-pandemic inflation peaked at 9.1%.

Overall consumer sentiment has fallen this year in the face of rising prices, a frozen job market and anxiety over a possible recession. But how high-income consumers feel about the economy “may help buoy consumption spending even amid views of the economy that are relatively subdued from a historical perspective,” according to the survey.

The Federal Reserve’s November Beige Book, which outlines economic conditions across the central bank’s 12 districts, reported an overall decline in consumer spending “while higher-end retail spending remained resilient.” In the Ninth District, which the Minneapolis Fed oversees, employment declined and prices rose.

The Mag 7 account for more than a third of the value of the S&P 500. Nvidia, which last year skyrocketed to the No. 1 spot as the go-to chipmaker for powering AI data centers, makes up about 8% of the index.

For comparison, the companies in that top spot at the end of 1990 (IBM), 2000 (GE) and 2010 (Exxon Mobil) comprised about 3%-4% of the S&P, according to research from Ameriprise.

Among Minnesota companies, UnitedHealth Group ranks highest on the S&P, hovering around No. 30. With a $300 billion market cap, it comprises about half a percent of the index.

The weight toward the Mag 7 and other tech stocks means the fortunes of the average 401(k)- or pension-holder are tied disproportionately to the fate of a handful of companies in a single industry.

“You have a market that is going to be very dependent upon the performance of those particular names,” said Craig Johnson, managing director and chief market technician at Piper Sandler.

Consider the week of Nov. 17, when investor anxiety about tech spending on CapEx – capital expenditures, such as data centers — led to a sell-off that produced a 1.9% drop in the S&P and a 2.7% drop in the more tech-heavy Nasdaq Composite.

Nvidia’s banner third-quarter earnings report allayed fears, and the markets ended the week on a positive note. CEO Jensen Huang, during the company’s Nov. 19 earnings call, addressed investor concern head-on.

“There has been a lot of talk about an AI bubble,” he said. “From our vantage point, we see something very different.”

The AI gold rush has prompted comparisons to the dot-com bubble, when CapEx spending on early Internet infrastructure outstripped demand. Of respondents to Bank of America’s November Global Fund Manager Survey, 45% said the biggest “tail risk” to the economy and the markets is the “AI bubble.”

Though the two moments rhyme, there are key differences. The Mag 7 includes established players like Microsoft, Apple and Amazon that have survived previous tech bubbles.

And so far, companies have been relying more on revenue for CapEx spending than debt, even though massive debt deals like Meta’s $27 billion to build a Louisiana data center have made recent headlines.

“The starting point is that these companies don’t really have any debt; their balance sheets are very healthy,” said Daniel Grosvenor, director of equity strategy at Oxford Economics. “It’s a risk that’s worth monitoring, but our view is that it’s not an immediate risk.”

Big Tech is expected to spend up to $7 trillion on capital investments by 2030, McKinsey estimated in April. Supporting the demand will require about $2 trillion in new revenue, according to a September report from Bain & Co.

What happens if the tech giants can’t deliver revenue to match their spending remains an open question investors are waiting to answer. In a worst-case-scenario comparison, the increasingly deregulated U.S. economy could be riding its second Roaring Twenties high. A century ago, that era of financial speculation after the Spanish flu pandemic crashed into the Great Depression.

For now, the stock market continues to power through headwinds, with the S&P 500 concluding its third-consecutive year of double-digit returns.

But the markets’ record-setting rise means they have further to fall.

“The concentration, while it has been great on the way up, might also be painful in a corrective phase,” Piper Sandler’s Johnson said. “People forget that coming out of the overhang of the dot-com bubble, it took multiple years before you actually saw a lot of tech stocks doing well again.”

©2025 The Minnesota Star Tribune. Visit at startribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments