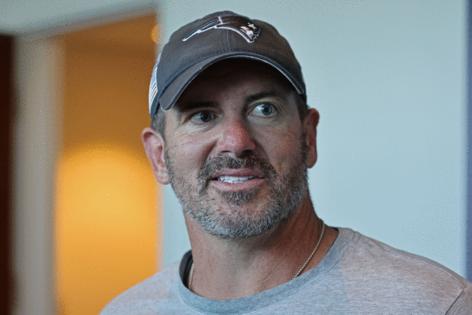

Andrew Callahan: The untold story of how a Patriots coach overcame alcoholism, PTSD to reach Super Bowl LX

Published in Football

BOSTON — How did Mike Smith get here?

Alone in a wooden cabin atop a remote mountain in Utah, hundreds of miles from home, sitting in the overnight dark. Days of solitude lay ahead of him, questions lingered behind.

Was it his fall in Green Bay?

That crash landing weeks before he worked Packers training camp in 2021, when he was one saw cut away from completing the roof on a backyard treehouse for his kids and instead dropped more than 20 feet, snapping ligaments in his right arm, crunching wrist bones to dust and activating old fractures in his back upon impact.

Was it his father?

The late Dan Smith, a Vietnam veteran, old-school west Texas cowboy who died in his son’s arms, a moment Mike would relive for months through night terrors and daytime flashbacks.

Was it the vodka Mike used to drown out that memory?

All those nights he counted a bottle as company and plunged himself further into the pain he thought he was escaping. Just as his old man did.

Before Smith flew to Utah in August 2023, he left his job as the Vikings outside linebackers coach. He walked into the head coach’s office right after the preseason opener, depressed and angry about things he could not change, and quit. Smith drove home and told his wife he was done. He needed to isolate, to dry out once and for all.

Weeks passed before the Vikings announced on Sept. 4 that Smith was on personal leave. Once the news broke, his phone pinged with texts and calls from all around the league. They all went unanswered.

Smith was unmoored from the only life he knew and loved. His passions had left him. The only thing he clung to was what he held in that cabin for almost 10 days: an old photo of his family.

In the photo, the Smiths are on an island beach where the waves have paused at their back. His wife, Emily, stands on the left in a bathing suit with their then infant daughter, Finley, on her left hip. On the right, Mike carries their other young children, Weston and Kennedy, one in each arm.

In the photo, his wife and kids smile.

In the cabin, he wept.

A father’s footsteps

Smith is alone again.

The 44-year-old is sitting on a sideline bench in Denver, where the Patriots just clinched the AFC championship amid a swirling snowstorm on Jan. 25. Tears of joy slip from his face into the powder below, as players dance and yell around midfield. Smith, who coaches the Patriots’ outside linebackers, has retreated so he can reflect.

Head in his hands, his mind drifts to a time and place that holds so much pain. But instead of hurt, he finds gratitude.

In the 18 months Smith spent out of football before joining Mike Vrabel’s staff last February, he came to believe his path, like all paths, was preordained. Every step that brought him to this snowy sideline, to his first Super Bowl and returned him to the warm embrace of his family was already written. Which means so was his sobriety, now two years and counting.

“People ask themselves if God’s real. I know he’s real,” Smith said. “My story tells me he’s real.”

If God was Smith’s guide through the valley of those 18 months, Smith’s father was his trailblazer.

Before he passed away at 73, Dan Smith was a gritty ranch hand, carpenter and contractor. He had a handlebar mustache that would have made Yosemite Sam jealous.

When Mike was eight years old, Dan and his mother divorced. The court sent Mike and his twin sister to live with their mother. But after a year, Mike couldn’t bear his father’s loneliness any longer and asked to move in with him.

In the two-bedroom apartment they now shared, Dan had a couch from Sears and a TV set that rested on a toolbox. He built a wooden frame around his son’s new bed, an air mattress, and gave him a TV tray to place his dinner every night. They were together, always.

“It was really just me and him,” Mike said.

Dan’s words were law in his house. If the old cowboy said wear this, you wore it. If he told you to eat that, you scarfed it down. Disobey, and it was time to prepare for a spanking.

Every day, Dan obeyed his own addictions, killing pain with packs of cigarettes and Coors banquet beers. Always the yellow bellies, never liquor. Some nights Dan came home. Others, he didn’t. He never explained why.

“Somebody like him, and how I was raised, you didn’t talk about emotion,” Mike said. “You didn’t talk about sadness.”

Dan’s hurt echoed through time when Mike’s surgically repaired wrist flared up in the winter of 2022. The pain reached a level even he, a former NFL linebacker, could barely withstand. Smith couldn’t sleep and began to self-medicate. Tito’s vodka over the yellow bellies.

A second surgery cleared out the metal in his wrist, where the screws had been inserted too far apart and different pins went in. The pain subsided, but remained. So his self-medicating continued in Minnesota, where he had moved from Green Bay to follow his longtime friend, new Vikings assistant head coach Mike Pettine.

As his wrist and back still ached from the treehouse fall, Smith’s heart broke next. He received a call about his father’s failing health that August and flew to their native Lubbock, Texas, where Dan’s strokes and years of chronic drinking and smoking were about to exact the ultimate toll.

The minute before he passed, surrounded by his three children, Dan looked his youngest son in the eye and sobbed. Until then, Mike had only seen his father cry twice: when he lost his mother and a brother. This would be the third and final time.

“I lost the man I loved the most,” Smith said. “Losing your parents is hard, no matter how you lose them, but I lost him in my arms, saw him take his last breath. I held him, and it really broke me.”

That memory haunted Smith all the way back to Minnesota, where the NFL season rolled on. Some nights he awoke in the middle of the night screaming in a cold sweat next to his wife. Others, he didn’t. He never explained why.

Not even football offered an escape.

“I’d be at practice and somebody’s talking to me, but I’m back in the hospital holding my dad like it’s happening again. I’m looking at him,” Smith said. “But I’m afraid. If I tell someone, is it going to come out that I am losing my mind?”

Even as visions interrupted Smith at work and booze numbed him at home, the Vikings seemed no wiser to his pain. Smith’s star pass rushers, Danielle Hunter and Z’Darius Smith, both topped 10 sacks. Minnesota glided to a 13-4 record and made the playoffs. Smith was the exact coach they wanted when they hired him, but the man had hollowed himself out.

“I’d go down to the basement and just sit there and drink. Then I’d sleep an hour or two, and I’d go to work about 4 a.m., and nobody could tell,” he said. “Because that’s the thing: my guys were performing.”

Eventually, his marriage crumbled. Smith moved in with Pettine in late February 2023, after he and Emily had separated. It took only a few nights for Pettine to hear the same overnight screams and cries she did.

About one week into living together, Pettine popped into Smith’s office at the Vikings’ facility and said to follow him down the hall. They stopped in front of an office Smith had never visited before. Pettine swung the door open to reveal a tidy room with a vacant chair and a man in a bow tie who rose to meet them. He extended his hand.

“Mike,” the man said, “I’m Dr. Young.”

Heartbreak to hope

Smith is by himself now, but hardly alone.

He’s standing at the front of the Patriots’ team meeting room one day last spring, presenting his “four H’s” during a team-building exercise Vrabel instituted so players and coaches share about one another; more specifically, their hometowns, heroes, heartbreaks and hopes. While he speaks, a picture of the late Dan Smith is projected on the screen behind him.

“He taught me everything,” Mike said. “My toughness, my work ethic, earning my paycheck.”

Mike revealed some, but not all, of what happened after Dan’s passing. Like, how he began talk therapy with the man in the bow tie, Vikings’ team psychiatrist, Dr. Larry Young; how it took 10 sessions for him to open up; how Dr. Young normalized his experiences as a textbook case of post-traumatic stress disorder; how, despite months of progress in therapy, separate stressors inside the team facility drove him out of football months later.

But those who heard what Smith shared in that meeting, who knew about his battles with alcohol, loss and a body racked with constant pain, could see he was winning the war. After several players and coaches took their turns and said winning the Super Bowl was their defining hope, Smith revealed his dream was simply to show up for his family. To be there.

In the audience, one of Smith’s players, sixth-year linebacker K’Lavon Chaisson, recognized his own pain in the coach’s story. Chaisson lost his father, Kelvin, when he was in high school. Kelvin was shot and killed during a domestic dispute. He was 33 years old.

“We share similar trauma and similar adversity that we fought to get where we are. He knows a lot of things might not be explainable and understandable going forward, but you have to find a way to make it make sense for you, and to continue to functionally go forward,” Chaisson said. “And I think he’s doing a great job with that. I appreciate him sharing his story.”

Sharing, Smith told his players, unlocked everything about his recovery. In the meeting, he compelled everyone to defy the stubborn, American male reflex to bury your pain. No, he said. Bring it to the light.

“You’ve got to be vulnerable. You’ve got to ask for help,” Smith said. “Any coach or player I worked with would tell you I’m a tough son of a b—. But I broke. I never thought that would, or could, ever happen to me.”

His words resonated. Soon enough, Smith became a light unto himself.

“Obviously we’re in two different rooms, but he’s a great dude, a good coach. He always makes me laugh,” said Patriots safety Jaylinn Hawkins. “He keeps us loose.”

Back in the fall of 2023, after returning from Utah and completing his withdrawal from alcohol, Smith started meeting with Dr. Young once a week outside the Vikings’ facility. By then, he had moved back into his house, but still slept apart from his wife. Smith filled his days coaching his son’s basketball and baseball teams, watching his daughters cheerlead, housework and hard introspection.

His marriage grew stronger when they moved closer to Emily’s family in southern Connecticut the following spring. The Smiths settled in a shore town, Madison, where they reside to this day. As he unpacked, Smith expected to take a job a close friend had offered him in another industry with a competitive salary.

But inexplicably, his friend went silent. The job fell through. Dozens of texts and calls went unanswered until the friend crawled out to confess he didn’t believe Smith would actually leave football like he had. That doubt left Mike and Emily, new homeowners with three mouths to feed, both painfully unemployed.

Unbowed, the old coach took interview classes and wrote his first resume. He created a LinkedIn profile and considered opening an athletic training facility. Emily found a job. Happy days returned.

But weeks later, they caught wind of a rumor spreading in league circles that Mike left football because of symptoms related to CTE. Circling back to the contacts he’d left hanging before his Utah trip, Smith sent more than 30 texts to set the record straight. He waited for feedback.

Smith estimates only five to 10 of them responded. Vrabel, whom he’d met years ago through ex-Patriots and mutual coaching friends Wes Welker and Larry Izzo, was one of them. No one else sent a text like Vrabel’s.

“It was just so detailed,” Smith said. “That it’s all about the family, and family is all that matters before you can ever think about coaching again. And I just thought, wow. Like, we were friends, but he’s really gonna send me something that long, sincere and that caring? I knew what kind of man he is.”

The summer and fall flew by. Smith coached his son’s new teams and maintained a tradition his father inspired decades ago: Blizzard Fridays. At the end of every school week, Smith picked up his kids and zipped them straight to a Dairy Queen the next town over. It didn’t matter the flavor, the week or the weather. Fridays, in the Smith household, are for ice cream.

On weekends, he avoided football for a second straight season, college and pro. That is, right up until the AFC Championship Game two Januarys ago. Kansas City, where he coached from 2016-18, had welcomed the Bills again with a trip to the Super Bowl at stake. Smith loved working for Chiefs coach Andy Reid, and was still friendly with several assistants on his staff.

Something stirred in Smith that afternoon. A warmth, he called it. He put the game on.

“I remember my wife coming down,” Smith said, “and she was shocked.”

Reinvigorated, he drove an hour and 15 minutes north and handed his resume to UConn coach Jim Mora just days later. He applied at the suggestion of a former graduate assistant, Matt Brock, the team’s defensive coordinator. Mora said they would be in touch.

Days after that, Smith went for one of his many long walks. This one crossed a bordering town, Killingworth, and again, something stirred.

Smith felt drawn to a tall white facade he could see through the woods just off the road. He walked down a short, paved driveway that led to the towering white building, a non-denominational church called Living Rock. He climbed the front steps, remembering all the Sundays in Texas he had done this as a child and all the Sundays he hadn’t since.

The church pastor approached him at the entrance. They chatted. Smith shared who he was and what was on his mind, listened and left.

“I know it sounds crazy, but the pastor said, ‘Everything happens for a reason. God will give you the desires of your heart,'” Smith said. “And so I keep walking, thinking about my purpose. Sure enough, later that day my phone rang.”

It was the new head coach of the Patriots.

“Where are you?” Vrabel asked, figuring his proud Texan friend had moved back or maybe stayed in Minnesota.

“About an hour and a half from you,” Smith said. “Connecticut.”

“What?!”

Smiling again

Smith is alone no more.

It’s his first day of work in New England, early February, and he’s hugging Patriots defensive coordinator Terrell Williams inside the team facility. Smith interviewed the day before in Foxborough, Mass., less than 24 hours after Vrabel called. Smith knows Williams made the final call to hire him, but feels most indebted to his new boss.

“I owe a lot of things to Mike Vrabel,” Smith said.

On his drives to and from Foxboro that week, he thought of his wife and Dr. Young. He thought of Pettine and Bob Sutton, another former coach turned confidant, and his last boss, Vikings coach Kevin O’Connell, who had endorsed him to Vrabel. He thought of Welker, his best friend and former teammate at Texas Tech, and all the phone calls Welker answered over the years.

“Wes got me through some s—,” Smith said. “I look back and feel bad. He’s coaching for the Dolphins, and we’re talking like twice a week. I was just breaking down crying on the phone.”

He thought of the impossible odds that he, a football lifer, would find himself living in Connecticut of all places, and then find a job within driving distance of his new home. Smith was the last position coach Vrabel added to his staff, and the only one on defense with whom he had zero prior working experience. Months after hiring him, Vrabel explained why Smith was an outlier during a press conference.

“Mike’s a good teacher,” Vrabel said last June. “He’s a very good pass rush teacher. He’s an excellent teacher who breaks film down, can explain moves, can show guys these (pass rush) moves. He’s coached a lot of good pass rushers.”

All of that teaching was ahead, just as his pain was now behind him.

After he embraced Williams that first day, Smith settled into his new office. He began to unpack his things and found the old beach photo. He taped it to a wall next to his desk. He stared for a moment.

In the photo, Emily and the kids smile.

This time, he smiled back.

____

©2026 MediaNews Group, Inc. Visit at bostonherald.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments