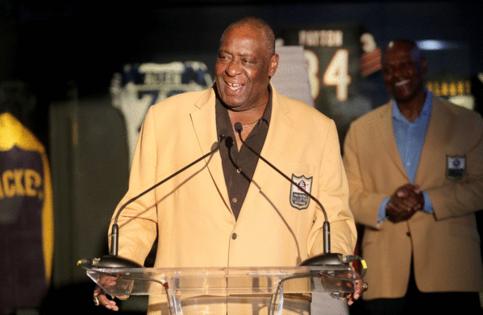

Dave Hyde: The '72 Dolphins win again -- and Larry Little shows it's more than a football story

Published in Football

Some days you wouldn’t wish this sports writing job on anyone. The headaches. The condescension. The constant riding the elevator down with good men at the low point of their careers in the manner it’s been with the Miami Dolphins for so much of the past two decades.

And then there are the other moments, the special moments, the ones like Monday after the final unbeaten teams of this NFL season were beaten and a simple a call to Larry Little to talk about his undefeated 1972 Dolphins involves a conversation through time that surprises you. Stretches you.

That perfect season takes on new dimensions when Little talks about growing up a fat kid in Miami who sat in the Orange Bowl’s segregated bleachers watching games, who bought the tasty hot dogs at McCrory’s store but couldn’t legally eat them at the counter and who snuck a drink at the white-only fountain in the W.D. Grant store to see if it tasted different.

“It did,’’ he said. “It was cold. Our ‘colored’ fountain was hot.”

You want to talk about overcoming adversity?

“I was told I would never be anything,’’ Little said. “My dad was an abusive alcoholic. He’d get drunk and want to fight my mom.”

He is an iconic name, the best guard in Dolphins history, a Hall of Famer, looking back at his life and his football at 79. And his view isn’t limited to a 100-yard field. He wrote about it in his autobiography, “From the Outhouse to the Penthouse."

“It’s about my journey,’’ he said.

That journey included bus trips while playing for Bethune-Cookman in the mid-1960s, when the driver was armed with toilet paper to distribute because the all-black team wasn’t allowed in public restrooms. Little tried once. He was stopped by a store owner holding a shotgun.

“I didn’t need to go that bad,’’ he said.

He didn’t hit a white player in football until he went to the San Diego Chargers in 1967. Dolphins general manager Joe Thomas traded for him before the 1968 offseason, one of five Hall of Famers Thomas acquired. You want to know what the Dolphins lack today? Quick: Name their next Little or Bob Griese or Larry Csonka.

That night of the trade, Little was in an Overtown bar when he bumped into a high school teammate, Mack Lamb, who played for the Dolphins.

“Great, we’ll be teammates again,’’ Lamb said.

“Mack, I’ve been traded for you,’’ Little said.

A “nothing-for-nothing trade,’’ the Chargers’ general manager, Sid Gilman called it. He rephrased it as the biggest mistake of his Hall of Fame career after Little because a centerpiece of the Dolphins offense in ways you might have read.

What you haven’t read is Little being told at the team facility that his brother, George, was murdered. He remembers the date, July 29, 1971, because it was his brother’s birthday. He hurried to tell his mother, a nurse’s aide, before someone else told her and then went to the morgue to identify his brother.

“I saw him laying on the slab,’’ Little said. “He was genius. He also was a junkie.”

Little and his heavy heart made his first Super Bowl that season. His Dolphins won rings the following two seasons, the franchise’s only championships, so distant now that Little has seen nearly half his teammates die.

Some people have tired of hearing about the 1972 Dolphins. And that’s fine. But they miss out understanding how they all led lives far beyond that season. Nick Buoniconti was CEO of two Fortune 500 companies before starting the Miami Project to Cure Paralysis. Doug Swift became a doctor; Dick Anderson a state senator. Bob Griese was the lead ABC announcer for college football.

Little became a coach at Bethune-Cookman, Division II North Carolina A&M and for a year in the World League.

“A good life,’’ he called it.

On Sunday, Philadelphia and Buffalo became the last NFL teams this year to lose games. So, the 1972 Dolphins’ perfect record remains intact for another year. But they aren’t just a football story, as Little shows. They’re a story of their times, one that still resonates in the manner of a fat kid from Overtown, Fla., about the successes he was told he’d never achieve.

____

©2025 South Florida Sun-Sentinel. Visit sun-sentinel.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments