Criminalization or support? Trump's executive order on homelessness gets mixed reaction

Published in Political News

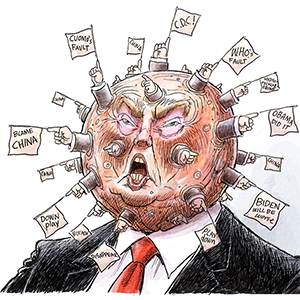

An executive order signed by President Donald Trump purporting to protect Americans from “endemic vagrancy, disorderly behavior, sudden confrontations, and violent attacks” attributed to homelessness has left local officials and homeless advocates outraged over its harsh tone while also grasping for a hopeful message in its fine print.

The order Trump signed Thursday would require federal agencies to reverse precedents or consent decrees that impede U.S. policy “encouraging civil commitment of individuals with mental illness who pose risks to themselves or the public or are living on the streets and cannot care for themselves.”

It ordered those agencies to “ensure the availability of funds to support encampment removal efforts.”

Depending on how that edict is carried out, it could extend a lifeline for Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass’ Inside Safe program, which has eliminated dozens of the city’s most notable encampments but faces budget challenges to maintain the hotel and motel beds that allow people to move indoors.

Responding to the order Friday, Bass said she was troubled that it called for ending street homelessness and moving people into rehabilitation facilities at the same time as the administration’s cuts to Medicaid have affected funding “streams for facilities for people to stay in, especially people who are disabled.”

“Of course I’m concerned about any punitive measures,” Bass said. “But first and foremost, if you want to end street homelessness, then you have got to have housing and services for people who are on the street.”

Kevin Murray, president and chief executive of the Weingart Center homeless services and housing agency, saw ambiguity in the language.

“I couldn’t tell whether he is offering money for people who want to do it his way or taking money away from people who don’t do it his way,” Murray said.

Others took their cue from the order’s provocative tone set in a preamble declaring that the overwhelming majority of the 274,224 people reported living on the street in 2024 “are addicted to drugs, have a mental health condition, or both.”

The order contradicted a growing body of research finding that substance use and mental illness, while significant, are not overriding factors in homelessness. “Nearly two-thirds of homeless individuals report having regularly used hard drugs like methamphetamines, cocaine, or opioids in their lifetimes. An equally large share of homeless individuals reported suffering from mental health conditions.”

A February study by the Benioff Homeless and Housing Initiative at UC San Francisco found that only about 37% of more than 3,000 homeless people surveyed in California were using illicit drugs regularly, but just over 65% reported having regularly used at some point in their lives. More than a third said their drug use had decreased after they became homeless and one in five interviewed in depth said they were seeking treatment but couldn’t get it.

“As with most executive orders, it doesn’t have much effect on its own,” said Steve Berg, chief policy officer for the National Alliance to End Homelessness. “It tells the federal agencies to do different things. Depending on how the federal agencies do those things, that’s what will have the impact.”

In concrete terms, the order seeks to divert funding from two pillars of mainstream homelessness practice, “housing first,” the prioritization of permanent housing over temporary shelter, and “harm reduction,” the rejection of abstinence as a condition of receiving services and housing.

According to the order, grants issued under the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration should “not fund programs that fail to achieve adequate outcomes, including so-called “harm reduction” or “safe consumption” efforts that only facilitate illegal drug use and its attendant harm.” And the Secretary of Health and Human Services and the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development should, to the extent permitted by law, end support for “housing first” policies that “deprioritize accountability and fail to promote treatment, recovery, and self-sufficiency.”

To some extent, those themes reflect shifts that have been underway in the state and local response to homelessness. Under pressure from Gov. Gavin Newsom, the California legislature established rules allowing relatives and service providers to refer people to court for treatment and expanded the definition of gravely disabled to include substance use.

Locally, Bass’ Inside Safe program and the county’s counterpart, Pathway Home, have prioritized expanding interim housing to get people off the streets immediately.

Trump’s order goes farther, though, wading into the controversial issue of how much coercion is justified in eliminating encampments.

The Attorney General and the other federal agencies, it said, should take steps to ensure that grants go to states and cities that enforce prohibitions on open illicit drug use, urban camping and loitering and squatting.

Homeless advocacy organizations saw those edicts as a push for criminalization of homelessness and mental illness.

“We’ll be back to the days of ‘One Flew Over the Cuckcoo’s Nest,’ “Berg said, referring to the 1962 novel and subsequent movie dramatizing oppressive conditions in mental health institutions.

Defending Housing First as a proven strategy that is the most cost-effective way to get people off the street, Berg said the order encourages agencies to use the money in less cost-effective ways.

“What we want to do is reduce homelessness,” he said. “I’m not sure that is the goal of the Trump administration.”

The National Homelessness Law Center said in a statement saying, “This Executive Order is rooted in outdated, racist myths about homelessness and will undoubtedly make homelessness worse. ... Trump’s actions will force more people into homelessness, divert taxpayer money away from people in need, and make it harder for local communities to solve homelessness.”

Murray, who describes himself as not a fan of Housing First, noted that key policies pressed in the order—civil commitment, encampment removal and substance use treatment—are already gaining prominence in the state and local response to homelessness.

“We all think if it came from Trump it is horrible,” Murray said. “It is certainly overbearing. It certainly misses some nuances of what real people with mental illness and substance use are like. But we’ve started down the path of most of this stuff.”

His main concern was that the order might be interpreted to apply to Section 8, the primary federal financial tool for getting homeless people into housing.

What would happen, he asked, if someone with a voucher refused treatment?

“It might encourage more people to stay on the streets,” he said. “Getting people into treatment isn’t easy.”

©2025 Los Angeles Times. Visit at latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments