Abolition wasn’t fueled by just moral or economic concerns – the booming whaling industry also helped sink slavery

Published in Political News

Historians have long debated whether the end of slavery in the United States was primarily driven by moral campaigns or economic changes. But what if both perspectives are looking at only part of the puzzle?

We are experts in economic development and social movements. Our new research uncovers what we believe to be a surprising and overlooked factor in the decline of slavery in the U.S. – the rise of the whaling industry.

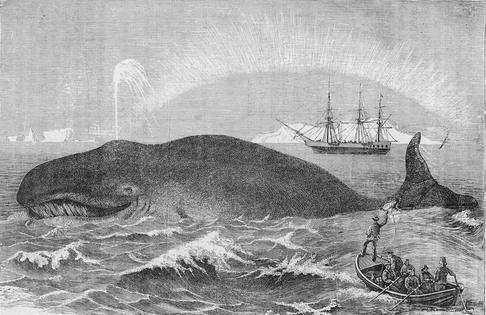

Starting around 1650, whaling expanded along the Northeast coast of the British American colonies. Whaling expeditions killed whales and brought back to port valuable animal products like oil, used for lamps and other items, and whalebone, used for products ranging from corsets to combs.

Whalers also brought spermaceti, a waxy substance that comes from a sperm whale’s head and is used to produce candles and lubricants for precision machinery like watches and clocks.

At its peak, in the 1850s, the American whaling industry alone employed 50,000 to 70,000 workers who worked on an estimated 700 to 800 ships.

In the decades before cheap oil helped many industries truly take off, whaling played an important, but often overlooked, role in laying the groundwork for the antislavery movement.

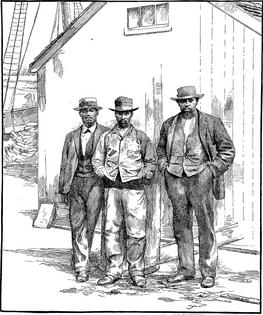

Black sailors made up perhaps 20% to 30% of whaling crews. Of these sailors, some were enslaved and used their hard-won earnings to buy their freedom. Some of these sailors went on to finance abolitionist efforts. Others built houses of worship.

The whaling industry that produced oil to illuminate 19th-century lamps also added fuel to the fire of the antislavery movement. The city motto of New Bedford, Massachusetts – lucem diffundo, or “I diffuse light” in Latin – referred to the candles and lamps the whaling industry lit, as well as the moral clarity some whalers aspired to promote.

Slavery in the American colonies began in 1619 with a small enslaved population that grew to about 500,000 by the American Revolution in 1775. As slavery became institutionalized in law and American culture, the number of enslaved people grew, primarily in the South, to as many as 4 million in the years leading up to the Civil War in 1861.

The first half of the 1800s saw a surge of abolitionist activism, rooted in early Quaker efforts and Indigenous wisdom. Abolitionism reshaped American politics into a fuller democracy, linking Black resistance, feminist struggles and labor rights to the broader fight for democracy and human rights.

The decline and eventual abolition of slavery has been portrayed as the result of tireless activism and moral persuasion by early Quaker advocates like Benjamin Lay who considered slavery one of the worst sins. Abolitionists like Frederick Douglass would later go on to advocate for the Civil War to force a moral reckoning on the South.

The result was an antislavery moral high ground from which the United Kingdom, and later the U.S., could measure other countries and monitor the high seas.

Another common explanation for the end of slavery is the economic argument that slavery declined as fossil fuel-powered machinery replaced enslaved labor on farms and even in factories.

Our research challenges this binary by showing that before steam engines transformed industry, whaling played an overlooked role in challenging the proposition that slavery was America’s most economically profitable form of labor organization at the time.

We analyzed data from U.S. Census records and the logbooks of American whaling voyages from 1790 to 1840 – systematized in a dataset maintained by the Mystic Seaport Museum and New Bedford Whaling Museum.

This data came from well before the 1859 discovery and exploitation of oil in Pennsylvania.

The results were striking: When the whaling industry brought back more oil, bone and spermaceti to specific ports, the proportion of enslaved people in the corresponding states declined.

Statistically speaking, we saw a nearly perfect 1-to-1 inverse relationship between whaling and slavery.

When whaling products went up 1%, slavery proportions went down by almost the same amount in that state in the following years. What’s more, we mapped these findings geographically and discovered that the more whaling occurred, the more widely decreases in slavery occurred in nearby states.

In other words, our statistics suggest that increases in whaling led to decreases in slavery, and this effect diffused across state lines.

Whaling was the first global industry in the colonies that eventually became the U.S.

Whaling hubs like the Massachusetts towns of Nantucket and New Bedford and the island of Martha’s Vineyard became some of the wealthiest communities in the country.

Whaling was also one of the few industries where Black Americans, both free and formerly enslaved, could make money and become wealthy. Individuals of all backgrounds could rise through the whaling industry ranks based on skill rather than birth.

It also required a risk-embracing and entrepreneurial mindset, as immortalized in a song that the writer Herman Melville has the crew sing in the 1851 book Moby-Dick: “So, be cheery, my lads! may your hearts never fail! / While the bold harpooner is striking the whale!”

By contrast, the plantation economy relied on rigid racial hierarchies and hereditary enslavement.

Prince Boston was one example of an enslaved whaler, who, in 1773 at the age of 23, won the right in the local Nantucket court to purchase his own freedom from his owner, who lived locally, with the money he earned on a harpoon crew.

This watershed moment saw the court make a precedent that was probably illegal at the time, but which supported and defended both the whaling industry as well as the aspirations of the people needed to make it thrive. Prince Boston’s free-born nephew, Absolom Boston, become the first Black whaling captain in 1822 – one of approximately 50 Black and Native captains in the American whaling industry throughout its history.

The economic power generated by whaling helped fund the abolitionist movement in tangible ways.

Wealthy Quaker merchants in whaling towns, like Martha’s Vineyard, were some of the earliest and most fervent supporters of abolition.

Elihu Coleman, a Nantucket Quaker, wrote one of the first antislavery pamphlets in America in 1733. Douglass, the famed abolitionist and formerly enslaved man from Maryland, found refuge in New Bedford, a whaling town with a strong antislavery tradition.

Whaling profits financed the construction of meeting houses and schools for free Black communities in these towns. The African Baptist Society in Nantucket, for example, was built by Black whalers who had achieved financial independence through their trade.

As an industry, whaling provided a meritocratic career path before fossil fuel mechanization made slavery obsolete. While industrialization eventually made enslaved labor less profitable by the mid- and late-1800s, whaling had already eroded slavery’s economic and social foundations decades earlier.

Of course, whaling itself was not a morally pure endeavor. It was dangerous and devastating to whale populations. The American whaling industry killed perhaps 32,000 whales over the 74 years between 1835 and 1909. The global harvest of whales was many times greater. The U.S. officially outlawed whaling in 1971.

Yet, whaling’s role in funding abolition and providing economic opportunities for free Black Americans is undeniable. It was, in many ways, a bridge between the world of forced labor and the energy-driven economy of the modern age.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Topher L. McDougal, University of San Diego and Austin Choi-Fitzpatrick, University of San Diego

Read more:

Juneteenth offers new ways to teach about slavery, Black perseverance and American history

What really started the American Civil War?

Slavery and war are tightly connected – but we had no idea just how much until we crunched the data

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Comments