Ronald Brownstein: The GOP tried loyalty, then rebellion. Both failed

Published in Op Eds

For Republicans, November was bookended by two ominous developments: Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene’s resignation and the party’s resounding defeats in the New Jersey and Virginia gubernatorial races.

The Republican candidates in those races — Jack Ciattarelli in New Jersey and Winsome Earle-Sears in Virginia — tried one strategy for dealing with President Donald Trump: appeasing him at all costs. Greene tried the other: showing some independence from the president. That both roads ended in disaster underscores how narrow a path is available next year to Republicans in competitive states and congressional districts.

Ciattarelli and Earle-Sears followed the course almost all elected Republicans have adopted since Trump reemerged as the party’s leader in the run-up to 2024. Both resolutely refused to criticize him, even when he took actions that demonstrably hurt their states (like suspending federal dollars for a transit tunnel linking New Jersey and New York, or laying off thousands of Virginians who work for the federal government).

Ciattarelli and Earle-Sears fatally refused to change course even as polls for months made clear that Trump’s tumultuous second term was bleeding his support. In the end, Ciattarelli and Earle-Sears were both flattened by a tidal wave of discontent over Trump: A solid majority of voters in both New Jersey and Virginia said they disapproved of his performance, and more than 90% of those disapprovers in both states backed the Democratic candidates, according to the Voter Poll conducted by SRSS. In both states, all of the demographics that moved toward Trump in 2024 (particularly young people and working-class minority voters) moved sharply back toward the Democratic candidates.

The landslide Democratic wins in both states sent a clear message to any GOP candidates facing competitive races: aligning too closely with Trump in this environment can be dangerous to your political future. But just weeks later, Greene’s resignation, under pressure from the president, offered a cautionary addendum: distancing too much from Trump also can be dangerous to your political future.

Few elected Republicans could claim a more consistent record of devotion to the president; in the video she released last week, Greene recounted how she flew back to Washington to vote against Trump’s second impeachment — the one that followed the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol — the same night her father had surgery for brain tumors. And yet, Trump dismissively labeled her a “traitor” as soon as she broke with him on a few high-profile issues, especially the release of the Justice Department’s Jeffrey Epstein files.

Greene has enough of an independent brand in her deeply conservative Georgia district that she might have survived the primary challenge Trump threatened against her. But even if she did, she faced the likelihood that she would be isolated and ostracized in the party, just like the other Republicans who Trump has excommunicated over the years.

Why, she asked in her video, should she labor to survive a “hurtful and hateful” primary where the president and his allies would spend “tens of millions of dollars … to destroy” her only to return to Washington, where she would be expected to defend him against another impeachment if Democrats regain the majority? In this tug of war with the White House, she concluded, it was better to just let go of the rope: “I refuse to be a ‘battered wife’ hoping it all goes away and gets better.”

The choices are even more excruciating for Republicans running in less reliably red areas. Among Republican strategists it’s become conventional wisdom that their candidates can’t win without Trump’s favor because that’s the key to turning out his base of irregular working-class voters. But even if turning out Trump’s base is necessary for Republicans in 2026, there’s virtually no chance it will be sufficient in competitive races.

Recent public polls have shown a solid majority of voters now disapprove of Trump’s performance in multiple states that will host key midterm Senate and gubernatorial races, such as North Carolina (53% disapproval), Michigan (56%) and New York (61%). Unless Trump dramatically recovers in those states over the next year, simple math says Republican candidates can’t win in them unless they capture a significantly larger share of voters who disapprove of Trump than Ciattarelli and Earle-Sears did. Yet they’ll have no chance of doing that unless they display the same independence that prompted the president’s thunderbolts against Greene.

Trump has sometimes bitten his lip over disagreements from Republicans holding seats in blue places, such as Maine Senator Susan Collins; he’s seemed to understand that they provide the tipping-point seats creating the Republican congressional majorities to advance his agenda, even if they occasionally vote against it. With Trump’s standing now so diminished in so many places, his best chance of holding on to his congressional majority may be to let more Republicans test the limits of his tolerance for dissent. The level of self-awareness and self-discipline such a strategy would require, however, has not exactly been a hallmark of Trump’s volatile political career.

____

This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

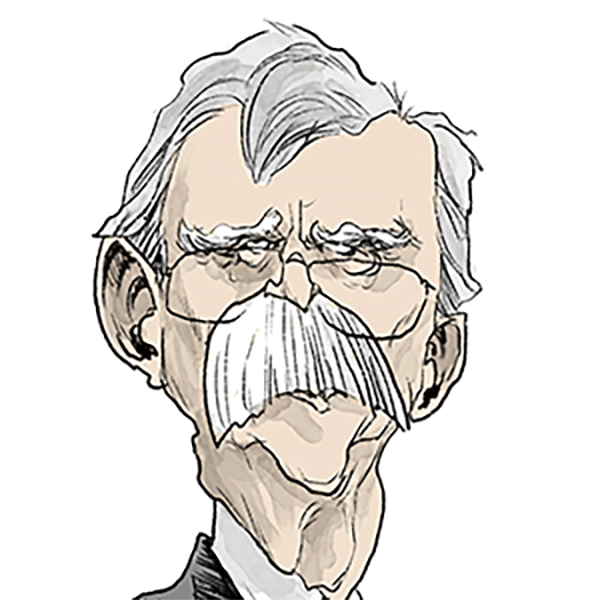

Ronald Brownstein is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering politics and policy. He is a CNN analyst and the author or editor of seven books.

©2025 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com/opinion. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments