Mark Gongloff: Bill Gates is wrong to quiet-quit the climate fight

Published in Op Eds

A few years ago, there was a big frenzy about “quiet quitting,” the idea that kids these days might show up to their jobs but not work very hard at them. Bill Gates seems to be quiet-quitting the fight against climate change.

The billionaire Microsoft Corp. founder has long led the charge to keep the planet from overheating, dedicating money and attention to the cause and helping make real change possible. He says he’s still in it. But his heart no longer appears to be. Worse, he’s giving ammunition to those fighting against further progress.

Fortunately, the rest of us don’t have to take our cues from him, given how misguided his reasoning is. Nor can we afford to.

In a note on his website titled “Three tough truths about climate,” Gates suggested negotiators at next month’s COP30 climate summit in Brazil should stop obsessing about global temperatures and instead help poor countries bolster their health and agricultural systems to withstand a planet that’s hot and getting hotter.

“This is a chance to refocus on the metric that should count even more than emissions and temperature change: improving lives,” Gates wrote.

He conceded the temperature goals of the 2015 Paris accords — limiting heating to 2 degrees Celsius above preindustrial averages, with a stretch goal of 1.5C — were doomed under current conditions but dismissed that as anything to truly worry about. “Although climate change will have serious consequences — particularly for people in the poorest countries — it will not lead to humanity’s demise,” he wrote.

If you’ve been watching Gates for the past few years, you might have seen this coming. Earlier this year, he cut policy staff at his climate group Breakthrough Energy. And in January 2024, he told a podcast, “The world does not end at 2C. In temperate-zone countries in terms of your overall economy or livelihoods, it’s actually not a gigantic thing. You have to pay to make various changes, you have to have air conditioning.”

“Humanity won’t go extinct” isn’t quite the reassuring message Gates seems to think it is. On the spectrum between “extinct” and “world peace and space elevators,” there lies infinite potential for human misery. The hotter the planet gets, the more that misery will abound — particularly among Earth’s most vulnerable people, as Gates acknowledges.

One big mistake is suggesting that letting developing nations burn fossil fuels until their living standards get up to speed will help them avoid some of this suffering. It’s a common Big Oil talking point, and it plays on the outdated notion that climate consequences are a tomorrow problem and that cheap, clean energy is a tomorrow solution. In fact, both are already here.

Floods, heat waves, droughts and supercharged cyclones are taking lives and destroying crops throughout the global South. Disease-bearing mosquitoes are expanding their territory. Burning more fossil fuels only extends and deepens this misery. Giving impoverished people AI-enabled mobile phones and access to genetically modified crops, as Gates proposes, is like putting a pimple star on a gunshot wound.

Gates’ note is also pretty optimistic about the future path of heating and humanity’s ability to adjust to it. He posts a chart showing temperatures gently sloping up to 2.9C by 2100 under current policies. He doesn’t account for the possibility those policies will be reversed with help from influential people like him declaring climate change no big deal.

Nor does he address the possibility that rising temperatures in a complex, chaotic system like Earth’s climate can trigger reactions that make further heating and human misery even more likely — things like burning rainforests, acidified oceans, dying coral reefs and collapsing ocean currents.

He acknowledges that people living near the equator will catch the worst of it, including “more heat waves, stronger storms, and bigger fires.” But that will simply require pausing “some outdoor work” and building cooling centers and early warning systems, maybe compatible with those AI-enabled phones.

It’s too bad 2021 Bill Gates didn’t build a time machine to talk to 2025 Bill Gates. Just four years ago, around the publication of his book, How to Avoid a Climate Disaster, he was talking about those tipping points, and he was much less sanguine about the outlook for the 3.6 billion people already living in places vulnerable to climate change, with the possibility of 1.2 billion climate refugees by midcentury.

“It’s going to be essentially unlivable at the equator by the end of the century,” Gates said in a 2021 Harvard talk, leading to “the instability of hundreds of millions of people trying to get out of those regions where a lot of the world’s population is, and particularly the poorest in the world.”

Today, Gates posits that new technologies will help us avoid such problems, with many ready to scale in the next decade. Among those are direct-air carbon capture, green steel and concrete, sustainable aviation fuels and clean hydrogen. Very few of those are currently close to scalable, if they’re ever going to be viable at all. Gates is correct that many deserve more investment, particularly in industries with emissions that are hard to abate. But if everybody follows his lead and abandons climate goals, then that investment will be scarcer.

In any event, cheap clean-energy sources are already available to improve lives in the global South, Jigar Shah, the former head of the Energy Department’s now-defunct Loan Programs Office, noted on Bluesky: “Solar plus batteries entrepreneurs are serving the 700 million people in extreme electricity poverty. We have solutions to the cold supply chain that are cheaper and better on climate.”

Gates also suggests economic growth will save lives, citing a Chicago Climate Impact Lab “thought experiment” that found the expected growth of developing countries could cut climate deaths in half. “It follows,” he writes, “that faster and more expansive growth will reduce deaths by even more.” Does it, though? Gates admits faster economic growth fueled by oil and gas is bad for the environment. Is there not another tipping point here, beyond which the returns of economic growth diminish?

What’s more, the economy on which Gates depends is directly threatened by those degrees of temperature he now tells us to ignore. Every 1C of warming reduces global GDP by 12%, or roughly $12 trillion in lost income every year, a 2024 National Bureau of Economic Research report estimated. Already $28 trillion in income was lost to climate change between 1991 and 2020, according to a recent study by Dartmouth College and Stanford University researchers in the journal Nature.

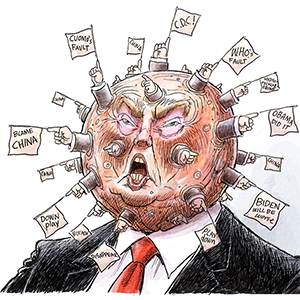

Essentially, Gates’ pitch is to favor climate adaptation over climate mitigation. Given how hard it seems to be to keep the world rowing in the same direction on the latter, choosing the former has a certain pragmatic appeal. Many countries, including large carbon polluters such as China and the European Union, still don’t have detailed plans for meeting their Paris emissions-cutting pledges. And the ones that do are woefully insufficient, according to a recent United Nations assessment. President Donald Trump has taken the U.S. out of the emissions-cutting game entirely.

But “pragmatism” is also the buzzword of the year in energy circles, touted by Trump’s climate-change-dismissing energy secretary, the former fracking executive Chris Wright, among other industry voices. In fact, Wright’s comments about climate are in many ways indistinguishable from what Gates is saying now. As my colleague Liam Denning has put it, surrendering like this may not be so much pragmatism as “fatalism.” Or maybe cynicism.

Gates has fallen short of his own promises on climate. His Breakthrough group still finances clean energy and other helpful projects. But his foundation also still invests in fossil fuels despite a 2019 pledge to divest, according to 2023 tax filings, the latest public disclosure with detailed investments. Gates’ note was partially addressed to COP30 participants, but Gates isn’t bothering to attend, the New York Times reported.

The impetus for his note seems to be Trump’s closing the U.S. Agency for International Development, cutting off desperately needed aid for developing countries around the world. Gates rightly describes this as a disaster, and he’s certainly within his rights to spend some of his fortune remedying it. Hopefully he’ll save many lives and alleviate much human suffering. But firing stray shots at climate action on his way out the door will only make that job harder.

____

This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Mark Gongloff is a Bloomberg Opinion editor and columnist covering climate change. He previously worked for Fortune.com, the Huffington Post and the Wall Street Journal.

©2025 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com/opinion. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments