Editorial: Punish politicians who lie? Good luck with that, UK

Published in Op Eds

No one struggles with moral quandaries quite like the British. In the plays of William Shakespeare alone, there’s a lesson in how not to deal with jealousy (Othello), how to screw up ambition (Macbeth) and the morality of revenge (Hamlet) with many, many more.

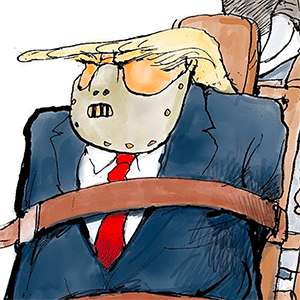

The royal family is an endless source for further examples of poor choices (albeit with less iambic pentameter) and how very, very British that President Donald Trump’s state visit with King Charles III this week caused a publicly owned television station, Channel 4, to run a Wednesday night special on Trump’s lies and misinformation. “Trump v The Truth” was promoted in advance as “the longest uninterrupted reel of untruths, falsehoods, and distortions ever broadcast on television.”

Small wonder that earlier this year the Welsh Senedd— the legislature governing Wales — set a new standard for members. Beginning with next year’s election, members of the Welsh parliament who lie could lose their seats. And that’s only the start.

Similarly aimed legislation, known as the Hillsborough Law, was introduced to the U.K. Parliament this week after years of discussion. The law would impose a “duty of candor” on public officials, who could face up to two years in prison if they knowingly mislead the public.

Given the skyrocketing volume of misinformation available online, the thinking goes, isn’t this the moment to punish public officials across the United Kingdom who deliberately lie? And guess who good government advocates in Great Britain inevitably mention when worst-case scenarios are invoked? Here’s a hint: He lives in a big white government building in Washington, D.C., and routinely stretches the truth to suit his needs.

We would be inclined to applaud the effort. Lying is, indeed, a bad thing. The problem is that everybody does it. And, as a result, enforcement would be challenging. And when we say “everybody,” we don’t just mean politicians, although they are certainly avid practitioners. Human civilization is practically built on lies. Advertising is so dominated by them (the next time the image of a burger looking enormous and plump in a fast-food ad resembles anything like what you’re handed at the drive-through will surely be the first time that happens) that it’s difficult to imagine life without commercial exaggerations.

Most politicians follow a pattern: They make big promises on the campaign trail and then express great surprise when they “discover” they can’t deliver on them after winning elected office. This isn’t exactly a recent development. “I no longer listen to what people say, I just watch what they do.” It was long claimed that former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill said that. Turns out he didn’t. Or at least that’s what the fact-checkers say. How perfect. But how exactly do you prove that what any candidate says was all a lie? People can also make assumptions about matters over which they have inadequate knowledge.

And then there’s a bigger problem: People want to hear those lies. The truth is often difficult. It can be uncertain. It can buck conventional wisdom. There is comfort in being told your views are always correct. This is at the center of the pitched, polarized and partisan battles that so beset the political culture in the U.S. (and, apparently, Great Britain) these days. One side is good, the other evil.

And how do we prefer to see ourselves? Always as the former. Oh, there are genuine evil-doers in the world, but they aren’t the root of the problem. The real challenge is the vast majority who see themselves as honest, principled and fair but can’t recognize when this moral superiority is often illusory. Or at least debatable.

Do we favor transparency? Of course. Accountability? Without question. Truth-telling? That’s the business we are in. But we’re also a little worried about naivete and a lack of understanding of how the world works. We live in an era when it’s more important than ever that people find reliable information and act on it. That doesn’t require a “truth police” out there making charges and punishing offenders.

Mostly, it requires people to be armed with a healthy dose of skepticism and to question what they find on the internet. It’s relatively easy to spot the letter from a phony prince looking to share his good fortune; it requires a bit more to flag misinformation that conveniently aligns with our worldview, as so many fell for in the wake of the assassination of Charlie Kirk last week.

No law seeking to punish politicians who lie can protect us from ourselves.

___

©2025 The Baltimore Sun. Visit at baltimoresun.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments