Science & Technology

/Knowledge

Editorial: Trump's gutting of environmental standards endangers Americans' health and finances

Fifty-six years ago, President Richard Nixon sent a letter to Congress proposing the formation of a new federal regulator: the Environmental Protection Agency. Back then, big city skylines were shrouded in smog, chemicals and waste had spoiled the nation’s waterways, and Americans across the political spectrum recognized the need to safeguard ...Read more

Nanoparticles and artificial intelligence can help researchers detect pollutants in water, soil and blood

Across the U.S., hundreds of sites on land or in lakes and rivers are heavily contaminated with hazardous waste produced by human activity. Many of these places, designated as Superfund sites by the Environmental Protection Agency, can be found in Houston, Texas, the city where my colleagues and I live and work.

Hazardous contaminants...Read more

Block to cut more than 4,000 jobs amid AI disruption of the workplace

Fintech company Block said Thursday that it's cutting more than 4,000 workers or nearly half of its workforce as artificial intelligence disrupts the way people work.

The Oakland parent company of payment services Square and Cash App saw its stock surge by more than 23% in after-hours trading after making the layoff announcement.

Jack Dorsey, ...Read more

NASA revamps Artemis plan, adding one more mission near Earth before moon landing

NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman announced a major overhaul of the agency’s Artemis mission plans on Friday, adding an extra mission next year to help the program better prepare for a moon landing in 2028.

And less than a year after nearly one-fifth of NASA’s workforce took a voluntary departure amid government-wide cuts, Isaacman now ...Read more

Sierra Nevada snowpack just 68% of normal after whiplash winter, but water supplies are OK, experts say

There’s still a month left, but this winter in California so far can be summed up in two words: roller coaster.

It began so dry that Lake Tahoe ski resorts couldn’t open for their usual Thanksgiving kickoff. Then 10 feet of snow fell around Christmas, saving ski season and bringing totals up to historic averages. But five weeks of warm, dry...Read more

NASA announces leadership shakeup in wake of Boeing Starliner criticism

A week after the NASA Administrator promised consequences for the agency’s mishandling of the Boeing Starliner saga, two key leaders of its Commercial Crew Program are being replaced.

NASA said that Ken Bowersox, who announced his retirement Wednesday, will be stepping down from his role as associate administrator of Space Operations Mission ...Read more

Battle of the AI brands: What's behind the bad blood between OpenAI and Anthropic

As more than 100 million people watched the Super Bowl, the battle for the future of artificial intelligence spilled out into a massive public arena.

In a series of viral commercials, AI upstart Anthropic broadcast to football fans that they should avoid AI with ads. The commercial was obviously targeting OpenAI, which plans to add ads to ...Read more

How natural hydrogen, hiding deep in the Earth, could serve as a new energy source

In the search for more, new and cleaner sources of energy, a largely untapped resource is emerging: natural hydrogen.

Unlike hydrogen produced from industrial processes, natural hydrogen forms through geological reactions that occur normally within the Earth’s crust, meaning it costs nothing to make – though it costs some amount ...Read more

The Mojave Desert is a hot spot for off-roading. Here's why a judge shut down more than 2,200 miles of trails

MOJAVE DESERT — The desert tortoise, a once-resilient reptile, is a keystone species in the Mojave Desert, where other animals depend for their survival on the burrows it digs.

But it is imperiled in California thanks in part to an unusual predator: off-road vehicles that race through thousands of miles of trails — official and unofficial �...Read more

Making sense of a chaotic planet: How understanding weather and climate risks depends on supercomputers like NCAR’s

Have you ever stopped to wonder how forecasters can predict the weather days in advance, or how scientists figure out how the climate might evolve under different policies?

The Earth system is a vast web of intertwined processes, from microscopic chemical reactions to towering storms. Ocean currents circulating deep in the Atlantic, ...Read more

How protecting wilderness could mean purposefully tending it, not just leaving it alone

More than 110 million acres of land across the U.S. are protected in 806 federally designated wilderness areas – together an area slightly larger than the state of California. For the most part, these places have been left alone for decades, in keeping with the 1964 Wilderness Act’s directive that they be “untrammeled by man.”

...Read more

The cost of casting animals as heroes and villains in conservation science

Scientists are philosophers, explorers, data collectors and number crunchers. They are also storytellers, placing data within a broader scientific and societal context. How they tell these stories matters.

In our work as ecologists, we find that the “hero-villain” narrative trope is a popular tool in ecology and conservation ...Read more

'It's a wake-up call': US biotechs discuss why we've fallen behind China

Perched on the cliffs of Torrey Pines in San Diego, investors, CEOs, and scientists this week debated whether U.S. biotechs are losing ground to China. Meanwhile, across the Pacific, Chinese companies were busy inking deals.

“There’s never been a question of whether China will be the leader in biotech. It will absolutely be the leader. The ...Read more

Rare Sierra Nevada red fox spotted near Tahoe, may be making a comeback

A rare and threatened species of red fox has been spotted in the Tahoe Basin for the first time since the mid-1900s, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife announced.

The Sierra Nevada red fox strolled through the Blackwood Canyon area in Placer County, sniffing at some downed tree branches before heading off into the night — his ...Read more

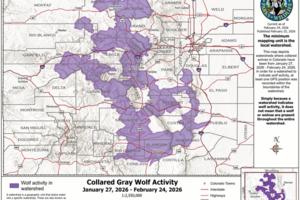

Colorado wolves pushed farther into the southern Front Range this month

DENVER — Two wolves roamed separately into the southern end of Colorado’s Front Range mountains in February, passing through watersheds west of Pueblo and Colorado Springs, a map released Wednesday by Colorado Parks and Wildlife shows.

The wolves wandered farther southeast than tracking previously had recorded, but no wolves have spent time...Read more

Anthropic drops hallmark safety pledge in race with AI peers

Anthropic PBC, which for years billed itself as a safer alternative to artificial intelligence rivals, has loosened its commitment to maintaining its guardrails, one of the most dramatic policy shifts in the AI industry yet as startups once focused on helping humanity turn their attention to profit and success.

The company in 2023 said in its ...Read more

Deadly bird flu found in California elephant seals for the first time

The H5N1 bird flu virus that devastated South American elephant seal populations has been confirmed in seals at California's Año Nuevo State Park, researchers from the University of California, Davis and the University of California, Santa Cruz announced Wednesday.

The virus has ravaged wild, commercial and domestic animals across the globe ...Read more

Southern California's celebrity eagles Jackie and Shadow welcome new egg after ravens destroy first clutch

LOS ANGELES — An egg-citing plot twist has emerged in what’s already been an eventful nesting season for Big Bear’s celebrity bald eagle couple

Jackie laid an egg on Tuesday afternoon, offering new hope for babies this year after a previous clutch was eaten by ravens.

Before the egg arrived, just shy of 2:30 p.m., Jackie spent much of ...Read more

H5N1 bird flu found in California elephant seals for the first time

The H5N1 bird flu virus that devastated South America’s elephant seal populations has been confirmed in seals at California’s Año Nuevo State Park, researchers from the University of California, Davis and the University of California, Santa Cruz announced Wednesday.

The virus has ravaged wild, commercial and domestic animals across the ...Read more

NASA astronaut Mike Fincke reveals his medical incident reason behind Crew-11 return

NASA astronaut Mike Fincke announced Wednesday that it was his medical incident aboard the International Space Station in January that prompted the agency to return the SpaceX Crew-11 mission to Earth early.

“On Jan. 7, while aboard the International Space Station, I experienced a medical event that required immediate attention from my ...Read more

Popular Stories

- Editorial: Trump's gutting of environmental standards endangers Americans' health and finances

- Nanoparticles and artificial intelligence can help researchers detect pollutants in water, soil and blood

- How natural hydrogen, hiding deep in the Earth, could serve as a new energy source

- NASA astronaut Mike Fincke reveals his medical incident reason behind Crew-11 return

- NASA revamps Artemis plan, adding one more mission near Earth before moon landing