Are mass deportations Christian? Florida leaders contemplate the question

Published in Religious News

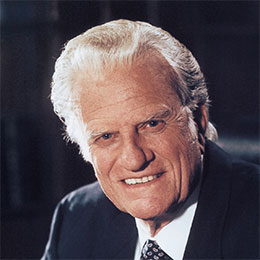

Thomas Wenski, the archbishop of Miami, has been working with immigrants in Miami for going on 50 years.

His flock is worried. Although thousands of recent immigrants in his Catholic archdiocese are here legally, many know people who are not. Florida is home to some 1.2 million people who are in the country illegally.

Some of Wenski’s parishioners remain tenuously in the U.S. because of humanitarian programs like Temporary Protected Status that were expanded during Joe Biden’s presidency. The Trump administration plans to scale back these programs.

“Many of these people are quite frankly very anxious — living in fear — because they know that their countries are not in a position to receive them," Wenski said in an interview, pointing to President Donald Trump’s promise of mass deportations.

Florida Republican leaders are largely aligned on immigration. On Monday, House Speaker Daniel Perez, Senate President Ben Albritton and Gov. Ron DeSantis announced they had reached a deal that they say would put Florida among the nation’s leaders in assisting with Trump’s immigration crackdown. Their stance appears to be in line with American voter sentiment about mass deportations.

But underneath this political consensus, there’s a religious debate echoing across the state, online and in churches. On Monday, Pope Francis, the Catholic Church’s leader, wrote a letter to American bishops decrying mass deportations.

“The act of deporting people who in many cases have left their own land for reasons of extreme poverty, insecurity, exploitation, persecution or serious deterioration of the environment, damages the dignity of many men and women, and of entire families,” Francis wrote.

Defenders of the crackdown in the faith community say it’s in keeping with the Christian tradition for leaders to protect citizens against potentially dangerous interlopers.

The Bible does not weigh in directly on the subject of deportation, noted John Stemberger, an evangelical Christian and the president of the conservative group Liberty Counsel Action.

Some passages seem sympathetic to the anti-deportation view. (Exodus 22:21: “Do not mistreat or oppress a foreigner, for you were foreigners in Egypt.”) Others talk about the importance of following the rule of law, which some say could be seen as justification for deportations. (1 Peter 2:13-14: “Submit yourselves for the Lord’s sake to every human authority: whether to the emperor, as the supreme authority, or to governors...”)

Stemberger, a prominent Florida activist who has pushed for restricting abortion access and gay marriage in the state, said leaders should defer to practical policy concerns when there is tension in the scripture on an issue. In the eyes of some conservatives, who often spotlight crimes committed by people in the country illegally, that means a hard line approach on immigration is justified to keep communities safe.

DeSantis, Perez and Albritton are all Christians. DeSantis, raised Catholic, has long found some of his strongest supporters in the religious community. The Florida Conference of Catholic Bishops has lobbied in favor of DeSantis' various anti-abortion efforts. His 2024 campaign for president was largely built on wooing Iowa’s conservative evangelical voters.

A political spokesperson did not respond to questions about how DeSantis views the theological debate around illegal immigration.

Vice President JD Vance, also a Catholic, has defended the administration’s immigration policy. He’s described the obligation of the Christian as a moral hierarchy. One must care first for his own household before he can check on his neighbor’s, or a person living across the city, or across the country or internationally, Vance has argued.

And he’s criticized Catholic leaders, saying they are more concerned about the payments they receive for helping resettle immigrants than about the country in which they serve.

“Are they worried about humanitarian concerns?” Vance said in a television interview on Jan. 26. “Or are they actually worried about their bottom line?”

In his letter, the pope seemed to explicitly refute Vance’s idea of a Christian moral pecking order.

“Christian love is not a concentric expansion of interests that little by little extend to other persons and groups,” he wrote.

The tension between American Catholic political leaders and those at the top of the church is nothing new. Pope Francis called Biden’s support for abortion “incoherence.” DeSantis has signed at least 10 death warrants during his time in office; the Catholic Church is against the death penalty.

And the disagreement is not just a Catholic phenomenon. Florida evangelicals are also wrestling with how to square the need for public order with their faith. (No religious leader interviewed for this story disputed the need to deport those who committed crimes.)

“Is mass deportation the best we can do?” said Gabriel Salguero, an evangelical pastor and president of the National Latino Evangelical Coalition. “Or should we advocate for Congress to do its job and pass bipartisan immigration reform?”

Hebrews 13:2, Salguero noted, says: “Do not forget to show hospitality to strangers, for by so doing some people have shown hospitality to angels without knowing it.”

©2025 Tampa Bay Times. Visit at tampabay.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments