How these schools are integrating AI, from middle school to higher ed

Published in Lifestyles

ST. LOUIS — The class started the way classes normally do. Students filtered into the room, sat down and set their backpacks on the floor.

Instead of pulling out textbooks or notepads, however, the students pointed iPads at a QR code projected on a whiteboard at the front of the room. Within seconds, they were inside an "AI space" — a teacher-controlled, artificial intelligence-powered chatbot that engaged with students on the topic of the day.

On this day in September, Matt Carmody, a seventh grade math and science teacher at Lindbergh School District's Sperreng Middle School, had created the bot for students to ask it questions about rational numbers. Carmody began using AI spaces through the SchoolAI platform this school year.

"If there's something you don't know, you can ask it," Carmody told the class. "If you struggled with last night's worksheet, see if it could help you out."

St. Louis-area schools increasingly are incorporating AI into everyday work for teachers and students. Educators say they hope early, structured exposure will teach students how to use AI responsibly — and prepare them for the world as the rapidly expanding technology becomes a daily reality.

"It's our responsibility to teach them how to use this ethically and responsibly," said Colin Davitt, Lindbergh's director of artificial intelligence and blended learning.

In some districts, the work began a few years ago, and at a methodical pace as new tools gained popularity. In the last year, however, an AI boom has made chatbots more accessible and prevalent than ever.

ChatGPT, an AI program that can complete tasks or answer questions almost instantly, launched in November 2022, and now is the fourth-most visited website in the world.

School leaders, meanwhile, have tried to keep up. Many have blocked ChatGPT on school devices in an effort to prevent cheating or block access to inappropriate materials.

Educators do not want to block the technology entirely, however. Some districts gradually have woven AI into daily operations, using tools to help teachers provide targeted academic support and students a way to ask virtual "tutors" questions after school hours.

Most school districts are still in the early, cautious phases, setting guidelines and testing tools.

Kirkwood School District has launched "micro pilots" in a handful of classrooms for teachers to experiment with different programs. A committee of librarians, counselors and administrators spent the past 18 months vetting different tools and developing guidance for ethical use. Teachers in January will undergo professional development in AI.

Rockwood School District has greenlit staff and students to use several tools. It also has created an online course for high school students on how to use AI effectively and cite AI-assisted work. Rockwood students cannot access ChatGPT while on school devices, even when they are at home.

Hancock Place set a goal to have at least 75% of its high school teachers use AI tools by the end of the school year.

Michelle Dirksen, the district's director of technology, said teachers of all grade levels received access to Snorkl, Brisk and SchoolAI platforms.

“We’re trying at every age level to show teachers, one way or another, that they could use AI — not to replace their job, but to enhance what they’re already doing in the classroom and help with creativity," Dirksen said.

'A little scary'

Eighty-five percent of U.S. teachers used AI in at least one way in their classrooms during the 2024-2025 school year, and 86% of students used it for school or personal pursuits, according to a survey from the nonprofit Center for Democracy and Technology,

The same report warned AI in education comes with risks, including "troubling interactions" in which students use AI to "escape from real life" or for mental health support.

The authors concluded school leaders need to provide training and clear rules about how and when to use AI. They also stressed AI tools should be vetted before they are used by staff and students.

Several area school boards have adopted a model policy from the Missouri School Boards Association, which requires districts to have at least one "AI coordinator" to determine best practices and create an "AI Use Plan" on student safety and security.

In June, the state Department of Elementary and Secondary Education issued guidance on use of the technology. The guidance, in part, encouraged districts to provide ongoing professional development on the technology and ensure a "human-centered approach."

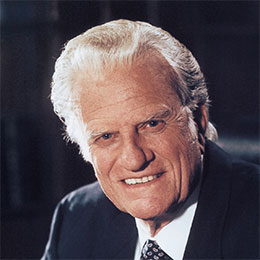

Eric Curts is a former middle school math teacher. He now is a technology coach who consults for schools districts. He spoke at an educator summit on AI hosted by Hancock Place over the summer.

The technology is not going to go away, Curts said. He equated it to computers and the internet, and how both now are so intertwined with education.

"We've always had technology in the classroom, in one form or another," Curts said. "We just have never had technology this powerful. I get it — that can be a little scary."

How it is used

Back at Sperreng Middle School, Carmody was, in a way, in 16 different places at the same time.

Students engaged with the chatbot the same way they would a teacher. It started with a prompt: "What do you know about rational numbers?"

Carmody monitored their progress on a tablet from the back of the classroom. SchoolAI told him which students were ahead and which could use more focused attention. He watched as one student correctly identified .5 as a rational number, and another asked for the definition of a rational number.

Extroverted students typically would dominate group discussions at the start of class, Carmody said. The chatbot forces each student to be engaged.

Carmody set the bot's parameters. He uploaded proficiency scales, tests and quizzes, so the bot would understand what students needed to know.

Teachers can tailor the AI spaces to students' age levels, and the tool will keep students focused if they try to stray from the topic.

"If they want to ask questions about celebrity gossip, it's going to redirect them," Carmody said.

Since May 2024, Lindbergh students also have had access to AI Chat by Securly, which they can use at home. It is similar to ChatGPT, but its conversations are limited to educational topics. Teachers monitor students' use.

Sophie Crecelius, a student in Carmody's class, said she likes using the AI chat at home when she's doing homework.

"It will just help you step-by-step, like how Mr. Carmody would help us," Sophie said.

Teachers at other area schools have used AI to help draft lesson plans, write emails to parents and brainstorm ideas. Some have trained chatbots to impersonate historical figures or fictional characters from literature to converse with students.

Liz Grana, assistant superintendent of curriculum and instruction for Kirkwood, shared an example of how a student used the MagicSchool platform to help write a poem that rhymed.

The program nudged the student along, asking questions, such as "Are you sure that word rhymes?" "What do you think is important to share here?" "Do you have a title for your poem?"

"It prompts the student to think creatively about what they're doing," Grana said.

In St. Louis, Lindbergh has been an early leader for integrating AI into the classroom.

The district is working with San Francisco-based Scale AI to build a training program for teachers on AI literacy, with a goal to have at least 20% of its teachers earn credentials in AI fundamentals by the 2026-2027 school year.

Scale, which has an office in downtown St. Louis, was one of dozens to sign onto the White House's "Pledge to American Youth," in which tech companies commit to providing grants, mentorship and expertise on AI.

AJ Segal, who leads Scale's St. Louis office, described Lindbergh's partnership as a "pilot."

"It's important to teach our kids how to incorporate (AI) into what they do every single day," Segal said.

Higher ed

Local colleges and universities also are leaning into the AI boom.

This fall, St. Louis Community College piloted MathGPT, a chatbot to help intermediate algebra students.

Webster University in May announced an AI-Assisted Learning and Instruction certificate for teachers.

Maryville University in Town and Country has invested tens of millions into the technology. The private school recently developed what it calls "social learning companions" that "live" inside certain online courses and act as study aids for students.

"It's kind of like a graduate assistant who never sleeps," said Michael Palmer, professor of informational systems and software development for Maryville.

Maryville has another bot named Mya, a virtual assistant created to help with recruitment for the school's online speech pathology program. A portal allows prospective students to ask questions about the program.

Perhaps the most striking example of AI in local schools is an AI-powered robot dog housed within the University of Missouri-St. Louis' Geospatial Collaborative.

"Triton," named after UMSL's mascot, Louie the Triton, can operate without human intervention (although it mostly is operated through a remote). Students programmed it to walk from the Geospatial Collaborative off Natural Bridge Road to UMSL's student center about a mile away. It uses AI to avoid walls and right itself if it falls over.

On a recent day, students in a geographic information systems class tinkered with Triton, learning how its laser could be used to scan rooms or worksites and create 3D models. The robot moved around the classroom much like a real dog would, albeit with a mechanical whir.

For educators, excitement surrounding the new technology comes with a level of restraint: How do they safeguard human connection and thought without sheltering students from an increasingly tech-enabled world?

"We want to keep our students creative, we want to keep them up to date with what's going on," Dirksen, the director of technology for Hancock Place, said. "We really just want to prepare them for what's ahead."

©2026 STLtoday.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments