Gaining ground: Native plants surge as gardeners try to save bees, butterflies

Published in Lifestyles

CHICAGO -- On a quiet street in Wilmette, Illinois, native plants bloom in broad sweeps and bright bursts, bringing color and life to what was once an ordinary strip of lawn separating the sidewalk from the curb.

The violet blossoms of blue vervain hover above clusters of frosty-white mountain mint, golden lanceleaf coreopsis, orange butterfly weed and pink poppy mallow. Monarch butterflies visit the buffet of pollen and nectar, as do wasps, bees, bugs and moths.

Humans pause as well, with a passing bicyclist turning her head to look and a man in an orange Kia pulling to a full stop.

“Awesome!” the man calls out to Amanda Nugent, who is standing nearby. “Is this your stuff?”

“It is,” Nugent says with a smile.

At a time of growing concern about declines in insect populations, native plants are having a moment, with local fans such as Nugent showcasing them in parkways and front yards and community garden walks featuring them alongside the traditional roses, salvias and lilies.

National trend data isn’t readily available, but the Northern Illinois Native Plant Gardeners Facebook page recently reached 10,000 members, up from 6,000 just two years ago. There’s also the Native Gardening in Illinois group with 6,500 members, and Native Plant Gardens in the Upper Midwest with 24,200 members.

The Chicago garden center Christy Webber reports spring native plant sales have almost doubled since 2023, from about $50,000 to $93,000.

And at the Monee native plant nursery Possibility Place, co-owner Tristan Shaw says his retail operation sold more native plants in the first eight months of 2025 than in all of 2024.

“There’s always been a core of people who have been preaching this (native plant) gospel, but it really just has gone crazy within the last 10 years, and especially within the last three or four,” said Bob Sullivan, an administrator of the Northern Illinois Facebook group.

People are turning to native plants for many reasons, including their natural good looks and low-maintenance profiles. But reports about declines in beneficial insects — including monarch butterflies and the federally endangered rusty patched bumblebee — have played a major role, observers say.

“Native gardening for many people is empowering,” Sullivan said. “It is something they can do that is rewarding, they see immediate benefits, and they’re getting a lot of reinforcement from scientists who are telling them, your yard really can make a difference.”

‘An amazing shift’

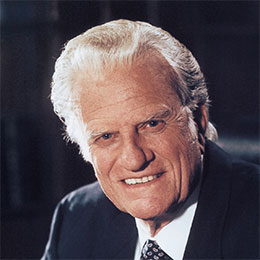

Amanda Nugent had always been interested in both gardening and conservation, but she didn’t really appreciate the connection between the two until she read the book “Bringing Nature Home” by University of Delaware entomology professor Doug Tallamy.

Tallamy, a bestselling author and a leader in the native gardening movement, is among the scientists who say that insects — a vital link in the food chain — are in trouble.

An influential 2017 study in the journal PLOS ONE found a 75% decrease in flying insects in German nature preserves over 27 years, and in 2021 the National Academies of Sciences produced a special issue on insect decline, with the authors of one article writing, “Urgent action is needed on behalf of nature.”

Birds, many of which eat insects, are also struggling, with a 2019 report in the journal Science estimating that there were 29% fewer birds in North America than there were in 1970.

Planting natives is a great way to help, Tallamy says. That’s in part because many insects are specialists that evolved to rely on certain naturally occurring plants. Among the better-known examples: Monarch butterflies need milkweed, the only plant their caterpillars will eat.

Tallamy wants ordinary gardeners to fight back against insect decline by supporting his vision of a 20-million acre “Homegrown National Park.” Roughly the size of Maine, this park-without-boundaries would consist of native plants, shrubs and trees grown on private land by gardeners doing their part to protect and sustain wildlife.

The idea is that as more native gardens join the “park,” they will start to provide continuous habitat for the insects that, in turn, support larger animals such as birds.

“It was a light bulb moment for me,” Nugent said of reading Tallamy’s book. She did some research and got increasingly excited about the ecological potential of her own lawn.

“I would wake up in the middle of the night thinking: What else can I support in my backyard?” she recalled.

Then the pandemic came, the program in which she taught elementary school nature science was canceled, and she found herself with more time on her hands.

She started her parkway garden, her first big native plant “experiment,” with a 4-by-4-foot bed between the sidewalk and the street. Every few weeks, the garden doubled in size. Today, it’s about 20 feet long, with natives flourishing alongside pollinator-friendly cultivars, or variations developed by humans.

Nugent also tore up half her front lawn and added a big bed of natives, and she shrunk the lawn in her backyard as much as she could.

Having basically run out of space for additional plants at home, she started a new career as a wildlife-friendly landscape designer.

Nugent has gone further than many native plant enthusiasts, but her journey reflects broader trends

Attitudes toward natives have shifted in recent years, according to Aster Hasle, a lead conservation ecologist at the Field Museum.

Hasle, who has studied how Chicago-area gardens can best support monarchs, points to the milkweed plant, once dismissed as a “highway weed.”

Today, milkweed is probably better known as “the monarch butterfly plant,” according to Hasle, who uses they/them pronouns.

“That’s an amazing shift,” they said.

Among the factors involved: In 2017 the rusty patched bumblebee — still seen in the Upper Midwest — became the first bumblebee to be granted federal endangered status. The buzz around the bee’s decline helped raise awareness of the plight of insects in general.

Hasle also points to broader public use of natives in public spaces, including in the Chicago Park District’s natural areas initiative, which now covers about 2,000 acres.

Hasle remembers a time when natives were hidden away in obscure places or placed behind shrubbery. Now native plants are highlighted — with, say, boardwalks for better viewing — and that sends a message, Hasle said.

“If it’s in the park, then it’s kind of like the government gave it its stamp of approval,” they said.

Similarly, the Field Museum installed its own large, colorful and prominently situated Rice Native Gardens, starting in 2016.

“I don’t think there was a moment when people said, ‘Oh, yeah, native plants are great.’ It’s been a lot of small shifts,” Hasle said.

Insects win fans

Chicagoan Loyda Paredes was just looking for plants that would do well in her yard.

By chance, the plants she found 10 years ago on an online store included native cultivars.

Then, over the years, as she experimented in her garden, learned from her local garden club, joined more Facebook groups, and read articles people recommended, she got interested in native plants themselves.

Being out in her garden and seeing the insects it supports has shifted her outlook, too.

“You start to learn,” said Paredes, a real estate agent. “It isn’t just the monarchs and bumblebees — there’s all these other insects that are beneficial and important and interesting.”

Paredes now has about 30 species of native plants growing in the front yard of her Northwest Side bungalow.

She has spotted a Carolina mantis on her property. But the eye-popping hummingbird moth, which does indeed look like a melding of the two creatures it’s named for, has (so far) eluded her.

“I’ve only seen videos,” she said.

Oak Park resident Judy Klem’s roots in native gardening go back further, but over time she, too, has leaned into the wildlife aspect.

Klem’s four children, now in their teens and early 20s, were still very young when she decided low-maintenance native plants were a good choice, given the demands on her time. She also wanted a pesticide-free yard that was great for the environment.

And she was inspired by Chicago’s influential Lurie Garden, which opened in 2004. The high-profile garden in Millennium Park has a naturalistic look and includes many native plants.

“They definitely turned the concept of a public garden up on its end,” said Klem, a nonprofit executive. “Once Lurie Garden demonstrated, ‘Here’s what you can do with a public space and look, it’s attracting all these interesting birds and butterflies,’ it was like, ‘Ooooh! I want some of that.’”

As time went on, Klem became more interested in the wildlife her garden sustains, including goldfinches, butterflies and bees.

Today, she keeps binoculars in the kitchen, so family members can enjoy backyard highlights such as a recent two-week visit by a fledgling cardinal.

“It was like this entertainment show in the backyard,” Klem said of the cardinal’s sojourn. “We were all sending pictures to the whole-family chat.”

Hopes and fears

During a tour of her garden, Nugent pointed out one insect after another.

There were the big black wasps, surprisingly striking with their iridescent blue sheen. There was the fluffy yellow and black bumblebee with bright orange “pollen baskets” on her hind legs.

“They’ll collect all this pollen on their bellies and fur and then at some point they’ll rest and use their legs to kind of rub it and collect it down into their pollen baskets, and pack it down,” Nugent said.

A hummingbird moth appeared as if on cue; an ailanthus webworm moth with jewel-like orange and white patterns running down its back crawled onto Nugent’s finger. A pair of fierce-looking ambush bugs mated on a boneset plant.

During a recent group tour of Nugent’s gardens, a black swallowtail emerged from its chrysalis, the hard covering that protects the insect as it transforms into a butterfly.

“That’s my favorite part: that there’s magic happening all the time — if we just look for it,” Nugent said.

Gardening with a purpose comes with its own pressures. Nugent said she worries that native plants aren’t catching on fast enough to head off the decline of insects.

“But then I spend the time in my yard, or my clients’ yards, and I see all the ‘buzz’ and I think, it’s all OK. And then I get hopeful,” she said.

©2025 Chicago Tribune. Visit at chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments