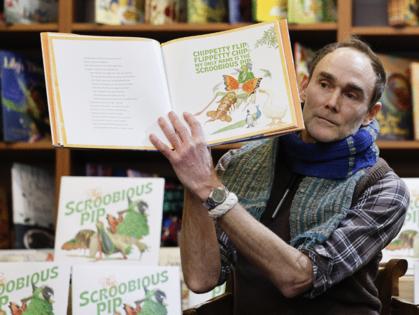

A celebrated Philly illustrator died before he could finish his last project. Then his son stepped in.

Published in Lifestyles

PHILADELPHIA -- “Just paint. You’ll find your way,” renowned Philadelphia illustrator Charles Santore told his youngest son, Nicholas, from his hospital bed at Pennsylvania Hospital one day in August 2019.

Nicholas, Nicky to his family, met his father’s advice with silence. He was an artist, and a very good one, but he hadn’t painted in quite some time. His reasons were complex and deeply personal.

The next day, 84-year-old Charles Santore was gone.

Not long afterward, Nicky and siblings Christina and Charles III met with a business associate of their father’s. The principal issue was The Scroobious Pip, an Edward Lear poem about a fanciful creature and the subject of a children’s book Santore was under contract to illustrate. He had done some of the work, but there was much left to complete and he had already received a partial advance from Philadelphia’s Running Press.

“So it was basically, ‘You guys are going to have to pay that back,’” Nicky Santore recalled. “Then my sister said, ‘He should do it,’ and she pointed at me. I was totally stunned.”

Everyone in that meeting seemed to agree it was a great idea — except Nicky, despite his degree from the Rhode Island School of Design and an MFA from Yale.

“I wasn’t sure I wanted to or could do it,” he said.

A journey unimagined

It was more than reluctance to step into the void left by his lauded father. Going back decades, art, once a bond, had become a source of unease, even tension, between this gifted father and son.

But Nicky, 51, a humble, gentle soul, would soon embark on a journey no one in his family — let alone himself — might have once imagined.

When their father unexpectedly took ill, just months after their mother Olenka died, the Santore siblings hoped he would recover. During that time, Christina spoke with Nicky about the possibility of helping their father finish illustrating the book, but Nicky said the decision had to be his father’s.

Christina, a writer living in Amsterdam, always had a soft spot for The Scroobious Pip, a poem that their father read to her as a child. Ironically, it was left unfinished by Lear at the time of his death.

“Nicky’s very modest, but he’s a man of extraordinary ability not only artistically, but in everything he does,” said Christina, 58. “For me, it’s a natural choice.”

Their brother Charles, a professional safecracker living in Los Angeles, also never doubted Nicky.

“I recognized this as a sort of family story,” Charles said, “a generational story about a father and son who don’t necessarily see things the same way. There wasn’t any hostility between them. But I thought, ‘How often in somebody’s life does somebody get to step in and get an opportunity to try something that may not come along.’”

Big talent, big personality

One might say Charles Santore did that himself. His was a Philadelphia story — big talent, big personality.

Raised in what is now Bella Vista, Santore was the eldest son of another Charles, a union organizer and boxer who has a branch of the Philadelphia Free Library named in his honor. The illustrator’s brothers, Bobby and Richie, founded the Saloon, an iconic South Philadelphia restaurant. Another brother Joe is an artist living in New York City.

Back then, all the guys who hung out on corners like Eighth and Christian knew how to use their fists.

But “Charlie was different from everybody; Charlie was unique,” his brother Joe said. “He was interested in music. He was interested in literature. For a while he wanted to be an actor.”

Charles Santore graduated from Edward W. Bok Technical High School and earned a full scholarship to the then-Philadelphia Museum School of Art. For decades, he was a sought-after commercial illustrator, finding success in children’s books in the 1980s. His TV Guide cover portrait of the comedian Redd Foxx hangs in the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery.

None of it was an accident.

Something of a wedge

“My father was a very, very disciplined person,” said Charles III. “That was true with the vitamins he took. It was true with his exercising in the morning. It was true with the way he went about his research and his work.”

Nicky had clear gifts as well. While at Yale, he pursued painting — not illustration like his famous father — and won Yale’s prestigious Ely Harwood Schless Award. During college, he took a class taught by his uncle Joe at the New York Studio School.

“His drawings were unique,” Joe said. “They had a different sensibility. They had a beautiful light and a beautiful quality.”

Charles Santore, too, was proud and supportive of his son, and Nicky admired his dad.

“I always looked up to him. Watching him as a little kid was like magic. And he always encouraged me,” Nicky said.

But as Nicky grew older, their differences in artistic approach became something of a wedge. Nicky loved art, but he craved other outlets for his energies — a mindset that ran counter to his father’s sense of strict discipline and single-minded dedication.

The summer after his first year at Yale, Nicky was supposed to complete a piece for a school show. Instead, he spent much of the summer surfing and playing in a band.

When his father discovered he’d left the project until late, they had words.

“He said, ‘If you want to get serious, you need to start to focus. You can’t surf. You can’t play music.’ And I was like, ‘This is part of me. I like doing this stuff.’ It was a challenging moment because I stood my ground, and he stood his ground. There really wasn’t anything resolved, but we both understood how we felt.”

After college, Nicky continued to make and show his art. But over time, with a family to raise and art income being fickle, it became less and less of a priority. “My father thought I should be making art despite not making a living off of it,” Nicky said.

In the ensuing years, he grew more distant from his artistic practice and pursued carpentry and continued playing in bands.

And then The Scroobious Pip came along.

Return to the studio

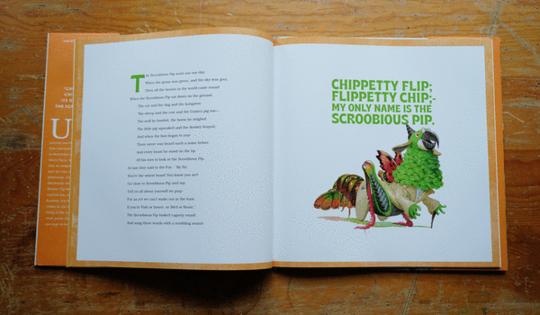

Nicky hesitated and suggested Running Press give him a tryout of sorts. It had been several years since he had done art at all. So he drew a small artwork with the Pip, the poem’s main creature his father had created that was part beast, bird, insect, and crustacean. It more than passed muster.

Eventually — perhaps inevitably — he chose to work at Charles Santore’s studio on South 20th Street, among his paints and brushes, his reference materials for the project, and the nine drawings and three paintings he’d finished. There, he sought simply, as his father had wished for him, to find his way.

The younger artist faced multiple challenges. Nicky was an oil-color painter and his father worked in watercolors, a medium much less forgiving of mistakes. His subject matter of choice hadn’t been the flora and fauna that populate the Pip’s world. Nicky decided to paint with watercolors, just as his father had done with the paintings he’d already completed.

But in that studio he found he had other common ground with his late father.

“I think my father and I approached things in a similar way,” Nicky said. “He would always say, ‘Never think you’re a professional. You’re always an amateur.’” That meant seeking a solution to what was in front of him that day, that moment.

So, like his father, he went to the studio every day and tried to figure out how to transform The Scroobious Pip into a book, to make it whole. And after three years of drawing and painting, he did.

Finally, a book

The Scroobious Pip, illustrated by Charles and Nicholas Santore, went on sale last month. It’s doing quite well, with a second reprint already ordered. The people at Running Press say they couldn’t be happier with the result.

“Everyone here loves it. I’m really proud of what Nick has done,” said Frances Soo Ping Chow, vice president and creative director of Running Press.

At the beginning of the project, Nicky was nervous, said Soo Ping Chow, who had worked with Charles Santore for many years. Finally, she said she told him, “This isn’t Charlie’s book anymore. This is your book now.” She advised, “‘Do what you’re happy with.’ And he did, and it turned out beautiful. It’s a work of art.”

The Santore family is pleased.

“It furthers our father’s legacy and furthers Nicky’s fine-arts journey,” Christina said. “I couldn’t ask for more.”

Charles believes his brother has honored their father and himself.

Uncle Joe is convinced his brother would have approved: “Charlie is smiling wherever he is.”

As for Nicky, he has started painting again. And he’s illustrating another children’s book for Running Press, The Three Witches, inspired by Shakespeare’s Macbeth. In true Nicky Santore fashion, he’s not yet claiming the label of illustrator, “even though that’s what I’m doing now because I don’t know what the future holds.”

But for the present, each day he goes to work in his father’s studio — now his studio, too. His life partner Valerie Ferus, also an artist, works there as well. It is a space of life again.

As an endnote to the book that now is both the father and son’s, Nicky added a dedication to his mother, which, he wrote, he was sure his father would’ve done.

But then, he added one of his own:

I would like to dedicate my contribution to this book to my father, Charles Santore, for giving me this opportunity to “just paint.”

©2025 The Philadelphia Inquirer, LLC. Visit at inquirer.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments