At-home care keeps his life steady. Missouri budget cuts could upend it

Published in Health & Fitness

KANSAS CITY, Mo. — When it snows in Parkville, Missouri, Harrison Long often stops in his tracks.

“Avalanche,” he shouts, even if only a few flakes are falling. It’s a line he memorized from a cartoon, one of the many TV show and movie quotes that have become commonplace in the Long household.

Harrison has also started singing again, reciting word-for-word the lyrics of old 1970s hits. He likes Earth, Wind & Fire. Every Saturday, he heads to a local diner for what his parents call “Breakfast Saturday,” a weekly tradition that keeps his world — and theirs — steady.

Harrison, 25, has level-three autism, a high-severity disorder that limits his speech and requires around-the-clock support. He relies on routine. And so do his parents, Berry and Shana Long, who shared Harrison’s story in an interview with The Star last week.

Now, proposed budget cuts in Missouri threaten to upend the Medicaid-backed program that makes those Saturdays, and the rest of Harrison’s carefully structured life, possible.

“I’m afraid he could shut down again,” said Shana Long, 60.

Missouri Gov. Mike Kehoe, a Republican, last month unveiled a proposed state budget that slashes funding for self-directed supports or SDS, a federal program that allows people with disabilities and their families to hire, train and manage their own care staff.

The Longs are among more than 3,500 Missouri families that utilize the program, which supporters say allows people with disabilities to live independently outside of institutional care. Others say that the program is more resistant to fraud and abuse because families play a direct role in managing their own care.

Kehoe’s proposed budget, which lawmakers will debate over the coming weeks, would cut the pay rate for employees who work with families like the Longs. Supporters of the program frame the cuts as devastating.

The budget has alarmed the families who have come to rely on at-home care. The Longs fear the sweeping cuts could force them to confront what they call an impossible choice: quitting their jobs to take care of Harrison full time or sending him to residential care, which can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars a year.

In a phone interview with The Star, Berry and Shana spoke glowingly about the progress their son has made in the program, where a team of three personal assistants carefully manages his care and takes him on outings around their home in Parkville.

But things weren’t always so promising.

A long search for care

Harrison struggles with changes to his routine, his parents told The Star.

He was attending Park Hill School District when COVID-19 forced him to stay home. The experience of not being able to go outside during the pandemic was traumatic, Shana Long said. Harrison lost some of the skills he had developed.

He wouldn’t get out of bed. He needed help dressing himself, making food and brushing his teeth.

“(He) basically just shut down,” Shana said.

With Harrison unable to go back to school, the Longs began a long-winding search for caregivers. They tried different agencies with no luck. One worker buried Harrison in paperwork he didn’t understand. Another moved without telling them. A third did not mesh with Harrison.

When they finally discovered self-directed care, it was the answer they were looking for.

Through the program, Berry and Shana were able to hire and train workers — called personal assistants or PAs — to meet Harrison’s needs.

“Now he’s able to stay engaged, stay regulated,” Shana said. “Stay happy.”

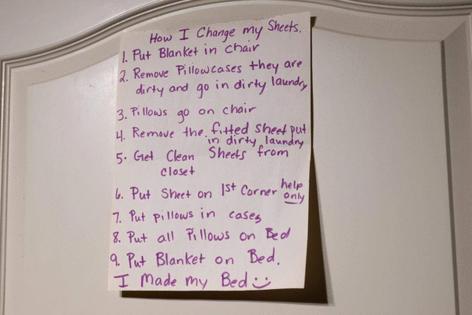

As Missouri lawmakers prepared to debate the state’s budget, supporters of the program began sharing their stories with legislators. Shana, in a letter to one lawmaker, described Harrison’s daily routine.

When the PA arrives each morning, Harrison brushes his teeth, takes his medicine and dresses himself, she wrote.

During the day, he volunteers at a local nonprofit and stocks the refrigerator, folds towels and sorts through bags. In the afternoon, he visits museums, libraries and the aquarium. Back at home, he does his chores: making his bed, cleaning his clothes and taking out the trash.

“With the folks that we have now, it’s more like Harrison’s peer group,” Berry, 62, said in an interview. “He can really identify with them because they’re close to the same age.”

Missouri’s cuts

One of those workers is Daniel Lewis, a 27-year-old who helps Harrison while getting a master’s degree in Behavioral Science.

Lewis pointed to the fact that self-directed care is much less expensive than residential care.

Online data from the Missouri Department of Mental Health, which oversees both types of care, echoes that argument. In fiscal year 2025, DMH reported that self-directed supports cost an average of $48,534 per person, while other types of care, such as state-operated facilities, can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars.

“It’s a really, really important service,” Lewis said in an interview. “It not only saves Missouri money, but it really provides extremely important…dignity and well-being for thousands of Missourians.”

But that service is now at risk.

Kehoe’s proposed budget, which he unveiled last month, would cut the program’s budget to 93% of the lower limit of the last rate study. In practice, the cuts would mean a $6.96 per hour cut to PA workers, according to the SDS Family Support Group, a group that advocates for the program.

“The cuts that he wants to make are — they’re devastating,” Lewis said. “Entire worlds of service are just going to be cut away.”

For Lewis, it means a 25% pay cut. Other workers in the program stand to lose a lot more, he said.

Victoria McMullen, who helped found the SDS support group, said employees are often paid at a higher rate — around $33 an hour for PAs — than other health care programs. That’s by design and intended to offset the fact that they do not have benefits, such as health insurance, paid time off, retirement plans and mileage, she said.

“That sounds like a whole lot, doesn’t it?” McMullen said. “But when you figure out how much an agency pays for health insurance and how much they pay for paid holidays and sick leave and unemployment insurance and workman’s comp, it’s equal.”

The cuts come as Missouri faces a major budget shortfall after years of being propped up by federal pandemic aid. For months, state officials have warned about the state’s more grim financial reality. Kehoe, for example, last summer slashed from the state budget $511 million in projects approved by state lawmakers.

Kehoe spokesperson Gabby Picard pointed to the state’s bleak financial situation in a statement to The Star, saying that the governor is recommending that lawmakers cut more than $600 million from the state’s operating budget.

Those cuts, Picard said, are intended to “prioritize fiscal discipline” while still meeting the state’s obligations.

“Given the seriousness of Missouri’s budget imbalance, tough decisions are being made to restore responsible spending across the entirety of state government,” Picard said, adding that Kehoe still believes the new rate would allow people to continue receiving care through the self-directed program.

Picard went on to say that payments to PA workers in the program had grown 443% since 2017. The new rate, she said, is still above the national average for direct support professionals.

But not all top officials are on board with the cuts to at-home care workers.

Rep. Betsy Fogle, a Springfield Democrat, serves as the top-ranking Democrat on the Missouri House Budget Committee. Fogle, in an interview, said she disagreed with Kehoe’s decision, juxtaposing the governor’s cut with his decision to sign legislation last year that eliminated the state’s capital gains tax.

“I’m very uncomfortable giving tax breaks to wealthy Missourians on the backs of making sure vulnerable Missourians and individuals with developmental disabilities are able to remain in a loving and caring home with a family who wants to care for them,” Fogle said. “I would say my priorities differ greatly from the governor on this specific item.”

Harrison’s future

For Berry and Shana Long, the program has allowed their son to live a fulfilling life. He’s singing again.

But they worry.

There are the logistical concerns. The cuts could cause Harrison to lose the care team he’s grown accustomed to. They could be forced to quit their jobs to care for him at home. Or they could sell their house and move. They might have to consider sending him to a residential facility.

And then there’s the effect on Harrison’s health.

“He will not understand that there’s not money for this,” said Shana. “He would just know that his life has changed.”

With severe autism, sudden changes to routine can result in changes in behavior, including self-injury, Shana said.

There’s also the looming element of time that comes with being a parent.

“One of our biggest fears as we approach our older years is that nobody will take care of your baby like you will take care of your baby,” said Berry. “But you will hope people will do the right thing and take care of their most vulnerable populations.”

How society treats the most vulnerable speaks volumes, Berry added. Shana agreed.

“These are humans,” she said. “They have a right to a life — their best life. They’re valuable. I just hate to see us in a situation where we’re othering people.”

©2026 The Kansas City Star. Visit kansascity.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC. ©2026 The Kansas City Star. Visit at kansascity.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments