In an indie comedy about estranged friends reuniting, rural Illinois takes center stage

Published in Entertainment News

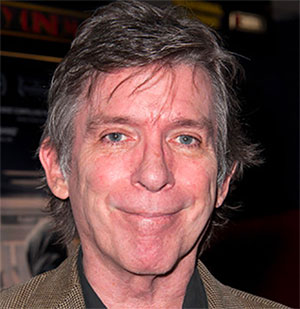

CHICAGO — In the ultra low-budget indie comedy “Everything Fun You Could Possibly Do in Aledo, Illinois,” Chicago theater actors Jennifer Estlin and Sara Sevigny star as estranged friends who reunite in middle age.

Brenda and Gabby were once childhood besties in the small town of Aledo. When their lives diverged after high school, they lost touch. Brenda stayed put after getting pregnant and subsequently got married. Now, three decades later, she’s a widow and a bored empty-nester. This is how Gabby, a world-traveler with three divorces under her belt who left town in search of adventure, finds her old friend when she returns home, hiding a few secrets that boil down to money troubles and a dissatisfaction with the way her supposedly glamorous life has turned out.

It’s an awkward and stilted reunion that is quickly smoothed over with wine and a trip down memory lane, including a bucket list (small town version) Gabby unearths that they wrote in their youth: “‘Make out with someone under the bleachers,” Brenda reads it aloud, unconvinced it’s worth pursuing. “Make out with someone in a corn field.’ This is just a lot of making out.”

“Ha, no wonder you got pregnant,” comes the reply.

Directed by Bethany Berg, it’s a minor comedy about minor midlife crises. The two pals aggravate and amuse each other in equal measure, and there’s a quiet sweetness to their antic friendship, with the film channeling a similar tone as the HBO series “Somebody Somewhere.” (The movie is available to rent on Amazon.)

“More than anything, I was drawn to the story of female friendship,” says Berg, “the kind where you reconnect after years without speaking and it feels like no time has passed. As we get older, there are versions of ourselves we think we’ve lost. But sometimes it just takes one person to bring that version back. If you can squeeze a 30-minute lunch with them into your schedule, you’re lucky. Spending a whole summer with them? That’s something that only happens in the movies. Well, at least this movie.

“I wanted Gabby and Brenda’s friendship to feel like they shed all those layers of resentment, guilt and responsibility that can build up over time, transforming back into their teenage selves. Laughing over stupid stuff, finding fun wherever they go, making fun of boys. Those are the kinds of female friendships I remember having as a girl. I don’t think you ever grow out of needing something like that — even as an adult.”

In an era where regurgitated intellectual property reigns supreme, a straightforwardly simple but meaningful original story can feel the most radical.

But the town of Aledo itself, with a population of about 3,500, might be the movie’s most distinctive choice.

“The movie is set in my family’s hometown on my dad’s side,” says producer and co-writer Christina Shaver. “What’s so interesting about this little town is that Suzy Bogguss (the country singer-songwriter), who is in our film, is from Aledo. And an up-and-coming country singer named Margo Price is also from Aledo, as is an artist named Gertrude Abercrombie, who had her work just sell at auction for over a million dollars. It’s a sweet little town that has given us some artists.”

Because Shaver frequently visited Aledo in childhood, she wanted to go back and film something there.

“Everyone in town was on our side and helping us out. We decided to shoot at the laundromat on a whim, like five minutes before, and I called the owner and he was like, ‘Yeah! Just lock up when you leave.’ We needed a golf cart and one of the women in town said, ‘You can use mine, just drive it back and leave the key on top when you’re done.’ It’s very low-key there. They were so supportive. So it was a very charming place to film and I think part of it was that the people there knew that my family is from there and that really went a long way.”

The budget was $200,000, a combination of “self-financing and also there is financing we got through an individual in Aledo who literally won the lottery,” per Shaver. A number of economies were required. “We shot in ‘live’ locations,” Shaver says, “meaning we didn’t close down many places when we filmed there, it was just whoever was there was included in the film, which I thought was great. It was a really interesting way to shoot a scripted film and also include elements of the town. I think that’s why the town really loves the film, because they see themselves in it, and it’s not a fictionalized version of themselves.”

Director Berg says, “We had the mayor on speed dial. We had the keys to the public pool. When we asked the local police if we could shut down a side road, they just shrugged, handed us traffic cones and said ‘You can try.’ I love Aledo. I love it more than Paris, Berlin and London combined. I almost don’t want you to publish this because I don’t want anyone else to shoot a movie there. It’s ours! Stay away!”

Shaver hopes to film other projects in Aledo as well. “We are looking to do a Christmas film in Aledo, so that’s next on the docket. And I have a documentary about Gertrude Abercrombie that we’re working on. She died in 1977, but she grew up in Aledo before moving to Hyde Park, where she was a surrealist painter. She was affiliated with jazz icons like Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker and Sonny Rollins, and she would host these amazing salons in her home. Sometimes the jazz artists would sleep over because it was segregated in Chicago in the ’40s and ’50s, so she would open up her home to them. Her art has gone from no one really knowing it to really blowing up in the art market right now.”

With the film industry in such a state of flux, how is that affecting Shaver’s efforts as a producer?

“So much feels derivative because people know what makes money and they just want to keep making money,” she says, “which is great, they should, that’s what their business is.

“But for me, my business is independent film and expressing myself through art, and that may not yield much revenue. So the way that I structured this film was not with the idea that I would make a ton of money from it. I would love to. But I’m making movies because of a desire to express something, not because I need the film to make a profit.”

©2026 Chicago Tribune. Visit chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments