John Huston's 'The Dead,' now a Criterion release: An appreciation

Published in Entertainment News

“Yes, the newspapers were right: snow was general all over Ireland. It was falling on every part of the dark central plain, on the treeless hills, falling softly upon the Bog of Allen and, farther westward, softly falling into the dark mutinous Shannon waves. It was falling, too, upon every part of the lonely churchyard on the hill where Michael Furey lay buried. It lay thickly drifted on the crooked crosses and headstones, on the spears of the little gate, on the barren thorns. His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.”

—James Joyce, “The Dead”

Quiet as the snowflakes it so memorably paints, James Joyce’s novella “The Dead” is a story in which little happens, but everything happens. The same can be said for John Huston’s 1987 film of Joyce’s work, a snow globe masterpiece that seems to place a compassionate hand on the shoulder of its viewer. In it, a group of friends and family gather for a festive dinner on a winter’s night in 1904 Dublin; later, a wife tells her husband a tragic story from her youth that he didn’t know. All the while, the snow falls, as it always has and always will.

I first watched Huston’s film when it originally came out, when I was in my 20s and didn’t know very much about loss, about the way tiny pieces of those who have left us remain with us forever. The film, finally being released by the Criterion Collection this month after decades of scarce visibility, hits differently for me now; its final scene is more devastating, and even more beautiful. Huston was at the end of his life when he made the film; you sense, watching it, that it’s intended as a goodbye, a last gentle embrace before parting.

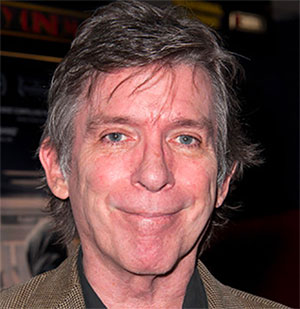

The film was made under almost unbearably poignant circumstances. Huston, after decades of legendary filmmaking (“The African Queen,” “The Asphalt Jungle,” “The Maltese Falcon”), was dying of emphysema by the time production began, tethered to an oxygen tank and unable to travel. Though he had longed to make the film in his adopted homeland of Ireland, he had to settle for flying in his entirely Irish cast to film on a California soundstage. It was his final film and very much a family affair, with Huston’s son Tony writing the screenplay (a very close adaptation of Joyce’s work), his daughter Anjelica starring as Gretta Conroy, and his son Danny leading a film crew to Ireland to shoot exteriors. The director died in August 1987, four months before the film’s release.

For much of its brief running time (a mere 83 minutes), Huston’s film immerses us in a social gathering, an annual Epiphany dinner long hosted by sociable Aunt Kate (Helena Carroll), frail Aunt Julia (Cathleen Delany) and their niece Mary Jane (Ingrid Craigie). Gabriel Conroy (Donal McCann) and his wife Gretta are honored guests; he carves the goose and makes a florid speech thanking the hostesses. Before dinner, there’s courtly dancing, and a concert, with Mary Jane playing the piano and Aunt Julia quaveringly singing the aria “Arrayed for the Bridal.” After dinner, the guests are sent out into the cold night, warmed by the evening’s hospitality.

Music — in the form of songs, and in the delicate rhythms of Irish voices in conversation — is a theme throughout Huston’s film, particularly in the way music brings back memories. Though Aunt Julia’s voice is now a shadow of what it once was, Delany’s performance lets us hear tiny hints of that former voice, like glimpses of sunshine breaking through clouds. And in a heartbreakingly lovely scene, we hear another impromptu concert: a visiting tenor, before his departure, sings “The Lass of Aughrim,” a traditional Irish song whose poignancy pierces something in the veil of Gretta’s memories. She stands on the staircase listening, posed in front of a stained-glass window with the still beauty of a church angel. Later, in their hotel room, she explains to an astonished Gabriel what this song means to her, how hearing that tenor brings back a devastating memory.

“The Dead” is one of the great literary adaptations, though quite different from the lavish Merchant-Ivory films of the ’80s and ’90s; this period piece is beautifully filmed in soft candlelight, but its sets and costumes are serviceable yet plain. It’s a work of remarkable subtlety, so much so that you might miss the way the camera occasionally wanders off to show us a photograph of someone now gone, or Gabriel’s reference to “absent friends that we miss,” or the way the tenor’s song softens Gretta’s face, making her suddenly younger again. And in that last scene, Huston has the confidence to simply let Joyce’s words take over, in the beautiful eternity of that snow falling “silver and dark.” The people we love, this wise movie gently tells us, don’t stay with us on this Earth forever, but neither do they leave us. The gifts they left behind, like that which Huston gave us, remain.

———

“The Dead”

Newly released from the Criterion Collection, $39.96 for two-disc set (one 4K UHD, one Blu-ray), $31.96 for Blu-ray only. Both versions include the documentary “John Huston and the Dubliners” as well as other special features. Information: criterion.com

———

©2026 The Seattle Times. Visit seattletimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments