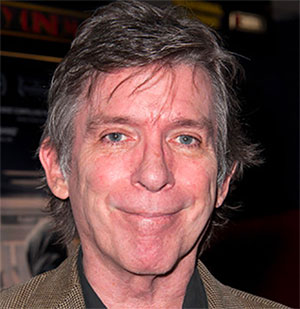

Q&A: Don Was talks John Mayer, staying sharp, curbing phone addiction

Published in Entertainment News

DETROIT — Don Was is a musician, a producer, a record label president, a radio host and a key figure in the music business going back to the 1970s. He's worked with everyone from Bob Dylan to Bonnie Raitt to Bob Seger to the B-52s to the Black Crowes, and that's just the Bs.

Ahead of a recent two-night stand with Don Was and the Pan-Detroit Ensemble in Ann Arbor, we talked to the Oak Park native, 73, about playing with his homegrown nine-piece band, staving off phone addiction, and working with superstar artists like John Mayer.

"Obliterating self-consciousness is the key to everything," says Was, on the phone in December from his home in Los Angeles. With that, here is our Q&A with the six-time Grammy winner and likely future Rock & Roll Hall of Famer. (Note: Questions and answers have been edited for length and clarity.)

Q: What is your relationship like with your phone? How do you interact with the news, and social media, and do you feel like you're able to take a break from those things? Or do you have a relatively healthy relationship with your device?

A: Well it's like cocaine, man. And I learned my lesson, you've gotta make an effort to stay away from that. (Laughs.) I had to get rid of a lot of the news apps, I had to get rid of Instagram. I'm on it, but somebody runs it for me. I don't even know how to sign on as me. You have to be careful: Dopamine's got dangerous allure.

Q: When did you find yourself in a position where you had to take some of those news apps and Instagram off your phone? Where you on them too heavily, and were they affecting your sense of peace?

A: Yeah. The news will make you want to throw up every day, literally. It's just so stressful. I can't remember more stressful times than these. There's a dichotomy: It's the citizen's responsibility to stay informed and to be active. And yet, if you're dead from a heart attack caused by the stress of the situation, you can't be much of an activist. So, you have to put your oxygen mask on first before you administer to the person in the seat next to you on the plane, right? So just for survival's sake, man, I've had to cut back.

Q: What do you do in that time that you're not spending, say, doomscrolling on Instagram?

A: I try to practice the bass. That's what was really suffering, man. As it is, I'm doing three jobs at once, so I don't have a whole lot of down time. It's all music related — I'm not lifting heavy boxes in a warehouse, that's hard work — but it's a lot. So like last night, there were like four or five different things I could have done, and what I did was I put up a multitrack of a Pan-Detroit Ensemble show that we played in October, and I took my bass out and played the show. Just practiced.

Q: Were you better or worse than the show?

A: I didn't play it back, I didn't record it, so I don't know. (Laughs.) If you wanna know the truth, when I was listening to the tapes, I felt I was getting too excited on stage. On one hand, that kind of seems like it would be a good thing. But it's not. What you want to do is be in this state, like meditation. The whole point of meditating is to get yourself in a state of mind where you're just existing in the present and are open but not thinking about other stuff, and particularly not worrying either about the past or the future or judging what you do in that moment. It's the exact same thing with playing. You want to get to a place where your fingers are kind of moving independently, where you open yourself up, accept the idea that the notes come from somewhere outside of you and flow through you, and you just want to keep your receptors up. That's the most important part about practicing is getting your head in the right place, so you're not blocking the flow of ideas that are coming from outside.

Q: When you heard yourself being too excited in the performance, how did that come across audibly?

A: Too many notes, and the wrong notes. You want to play the right notes, and by that I mean I don't mean if it's a C chord, play a C. I mean, more often than not, it's an alternative note — playing the third, playing the fifth — something that gives a little emotional impact to the chord as it's going by. So the bass player has a lot of options for coloring the feel of what everybody's playing. And the choice of notes, you want to choose the right one, and don't have a bunch of superfluous ones floating. That's just amateurish. The show I listened to was from Saxapahaw, just outside of Raleigh-Durham. It was a great show, really receptive audience. A lot of Dead heads, which means there's a lot of people who are really paying attention to the music and going on the journey with you. And I just got excited with the exchange of energy.

Q: But you have to be open to that as well, correct?

A: Well ... (laughs). I guess that's one way of looking at it. And also, you shouldn't isolate your own performance from the whole, really. It's the same with making records. You've gotta listen to the big picture. The big picture was great, band sounded great, and it definitely got over that night. People were were with us and there was a kind of collective euphoria. So it was fine, and you could take the approach that whatever you played was fine, because it worked. I just tune into the s—y notes, and me playing them too much. (Laughs.)

Q: Listening back, does it change your idea or perception of that performance at all? Or is it kind of like looking at game tape afterwards and studying what you've done?

A: You learn, and the fun part is learning. It's the journey. If you ever think you've got it mastered and you know it all, you're over as a musician. Improving is the adventure, man. That's the fun part. I did certain things playing that show last night, I stayed lower on the bass. I wasn't running around the neck so much. I stayed lower and in the pocket, and I think that was better. So that was a takeaway from that show. It's like we've already got a guitar player, a keyboard player and some horns playing up in that higher range, so there's really no need for me to be up there, stepping on their toes, when there's all this space on the bottom. You don't hear James Jamerson going up to high A-flat on the bass. He's in his area. I've gotten very friendly with Ron Carter, Detroit native, and probably one of the all-time great not only musicians, but bass players, and we were talking about that. It was the opposite with him. He told me that McCoy Tyner used to play too much left hand and get in the way of his notes, and he went over to the piano and he pointed to where it said Steinway, and he said, "everything to the right of the S, that's your territory. Everything below it, stay out of there. That's me." So I'm gonna stay to the left of the S. (Laughs.)

Q: Have you been to Sphere yet?

A: Yeah I saw Dead & Company there. Bob (Weir) has a box there, and I sat in his box, and it was the most magnificent thing I've seen, man. You know the Donald Fagen song "I.G.Y.?" That's kind of like my life story. They promised us this future in 1957, and sometimes it looks like the opposite of what they promised. But sometimes you actually get to a place where it's everything they told you it was going to be. I experienced that in Shanghai this year, a little bit in Tokyo. It feels like the future there. But the Sphere felt the most like, "Alright, you made it to the future. You lived to 2025." Everything about it, even the architecture and the lobby, it just feels fantastic, and it's such a great way to watch a show.

Q: At a Dead & Co. show — especially given your relationship with Bob Weir — how much are you able to just be an audience member, and how much are you playing along with the show in your mind? Where is your head at when you're in the audience at that show?

A: It's in a couple of places. Having played most of those songs with Bobby, I love seeing where it goes. I love hearing when Oteil (Burbridge, Dead & Co.'s bassist) does something that I never ever would have thought of doing. And there's another thing I listen to which, you know, I introduced (John) Mayer to Bob and Mickey (Hart). And I drove up with him when he went to play with those guys for the first time. I made three albums with John, I probably spent a year-and-a-half of my life with him. And it's fascinating to hear how his playing in that band has evolved, and how it's impacted other things that he's subsequently done. So that's the other thing I'm listening to.

Q: How did you introduce John Mayer to the Grateful Dead guys?

A: Here's what happened. Mickey and Bobby came to see me at Blue Note in the Capitol (Records) tower, it was in regards to releasing some of their solo music. And I'd already made two albums with John at that point, and I knew he was like a Grateful Dead fanatic. Every time we got in his car, that's what we listened to, the Grateful Dead Sirius channel. And he was one of these guys who can say, "No, that's not May of '88, 'cuz Jerry (Garcia) is using that Phlanger that he didn't get until after the summer," or something like that. He's that authoritative about it. So, he happened to be in Capitol studios the day Bobby and Mickey came to see me, so I called downstairs and said, "man, you won't believe who's in the office, you've gotta come up here!" So he came up and they just all hit it off, and they said, "Well, come up and jam with us sometime." So John, to his credit, man, he shut down what he was working on. He had all his gear in Studio B at Capitol and he was writing new songs. And he went home and he studied Jerry. He woodshedded Grateful Dead songs for about three months. This was September, and they said, "We'll get together in January," or something like that. So when he went up there, he wasn't doing karaoke Jerry, the goal was to absolutely not do that. But it was to try to extract the essence and find a way he could tap into that, while still being himself. And it's been so fascinating to hear the evolution of his playing with that band, where he sounds more and more like himself, and simultaneously more and more woven into the fabric of that band. So every time I go see them, I'm listening to how John locks in and how he elevates the audience, and then I also pay attention to what Oteil plays and his choices, and I marvel at him. He's such a virtuosic bass player. So it's in thirds: a third John, a third Oteil, and then a third just being a fan and digging the scene. You never get bored. (Laughs.)

Q: If I somehow convinced you to produce my album — and I don't have any musical skills to speak of, which I should note — what would we do in the room? What is the starting process you'd take with me to get, let's say, one good song out of me?

A: I think it starts with an overall vision, you know. Like, is there something you want to say? What's going on with you, what's happening in your life, what are you thinking about now? It's much better to go with the truth than to be an actor, you give a much more convincing performance. That's what I learned from Bonnie Raitt. I saw Bonnie Raitt turn down absolute hit songs, songs that absolutely would have been top 10 hits for her, because they didn't reflect what she was going through in that moment. One time, there was a great song that Paul Brady wrote about a relationship breaking up, and she had got married a month before. She said, "Well, I can't sing this song now," and she passed on it. It would have been a hit. So, the Stanislavski Method: tap into your life, what's on your mind, and how can we express it poetically. I would start there. It's not really about, "I want to make a record that sounds like Coldplay meets Mariah Carey," or something like that. So what are you going through? What do you want to talk about?

Q: I imagine on Thanksgiving you were watching the Lions, what were your thoughts on the halftime show with Jack White and Eminem?

A: It was beautiful, man. I love Jack, and I was at the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame when he got inducted. I played with Elton John, we did the Brian Wilson in memoriam tribute. I just love everything he does, and I love the way he comports himself. Everyone in Detroit knows where he's coming from, everyone gets it, and yet he does it with a combination of grace and inspiration. All you've gotta do is walk in the Third Man store. Look what this motherf----- built! It's incredible. When I go in there, I think, this is the kind of thing that everybody sits around and smokes a joint and says, "Oh man, let's open a store! All the products will be yellow and black, and we'll put a record pressing plant in the back! And everyone will wear lab coats, and it'll be a clean factory!" And you wake up the next day and there's no way you can pull it off, but this guy consistently pulls it off. To go from outrageous idea to reality is such a long journey, and it requires such perseverance, determination and patience. I've got a ton of admiration for Jack.

Q: What about watching movies, are you a movie guy at all? Have you seen anything good lately?

A: Yeah, I've been on a Japanese noir kick the last couple of weeks. I watched one last night called "Pale Flower" (1964), which is one of the most beautiful looking films I've ever seen. Some of the Japanese noir films are kind of campy and are reflecting, you know, it's a '60s version of '40s American stuff and French noir films. But some of these things are really, really deep and profound. There's another one that I found really relevant to music that I watched two nights ago, "Branded to Kill" (1967), Seijun Suzuki's the director. It's commentary about the genre — it's all about Yakuza hitmen, basically — but it's really about the No. 3 gun for hire, and he's trying to be No. 1, and it's about the emptiness of being No. 1, basically. So it's universal. Just a brilliant film.

Q: What was the first album you owned that you picked out on your own that was yours, and what did it mean to you?

A: When I started buying records I was in fifth grade, I think, and what I bought were 45s. Albums were just like the two hit singles and then filler, so it wasn't so album-oriented. But I could tell you the first single I bought was the Four Seasons' "Marlena" with "Candy Girl" on the B-side, and I played them to death, man. I played them over and over and over again, and there was something refreshing about that. You couldn't fast forward, you couldn't skip to the next song — you had to walk across the room if you wanted to change the record. Also, you didn't have all these choices, you had to listen to what you bought. So you'd listen to it a lot. And after 30 listens, you'd hear different things, and it would mean something different to you. So I remember that, and I think my cousin, for a birthday present, got me "Blue Velvet" by Bobby Vinton. I think those were the first two singles I had.

Q: You're going back out on tour with the Pan-Detroit Ensemble. How do you feel about where you are as a band, and how do you feel about where you're heading?

A: I love it, man. I know what the next moves are, and I feel the thing evolving a really rapid rate, which is exciting. The most exciting thing is I can't wait to see what happens when we play for six weeks straight without interruption. The band is constantly evolving. It's definitely now the kind of thing where if any one of the nine people in the band can't make a gig, we just don't do the gig. You can't have subs. It's absolutely the sound of these nine individuals playing together. It's a thing, it's now a living organism.

Q: How does it compare to what you first set out to do when putting this band together?

A: I knew within the first 10 minutes that there was a musical conversation going on among these individuals that was stimulating and simpatico. There were no stragglers in this thing. Everyone listened to everybody else and played generously. And being from Detroit — everybody's from Detroit, everybody lives in Detroit, I'm the only one who's half-time with two residences — and we grew up listening to the same radio stations and playing in the same bars and playing with the same people. And there's a common musical language that we speak that was evident in the first 10 minutes. So that alone is rare, to get nine people in a room, and it felt like we've been playing together for 10 years. The only pre-show agreement is that whatever we did last night, don't do it again, because no one else is going to be where they were last night. So just be fresh, and that's the fun. That's the adventure. I love being in this band, with all these players who are so accomplished and astute and open-minded. I wanna play with this band 'til I die.

©2026 The Detroit News. Visit detroitnews.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments