Michael Osterholm on the next pandemic, which he says will be worse

Published in Books News

Any time Michael Osterholm needs inspiration to continue fighting for public health, he glances at a gift on his desk, a Christmas present from his two adult children.

“It’s an electronic picture frame and they keep putting in pictures of my five grandkids,” said Osterholm, an internationally renowned epidemiologist who leads the “Osterholm Update” podcast and founded the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota. “I sit at my desk and watch all these pictures go across the screen and I don’t need any more reason to do what I do than to say, ‘What kind of world are we leaving for those kids?’”

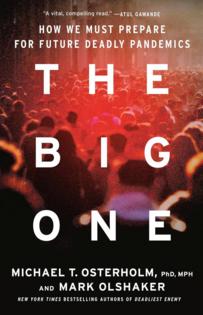

That’s the message of “The Big One,” written by Osterholm and frequent collaborator Mark Olshaker. The work of nonfiction incorporates COVID, influenza and other public health nightmares to look at future pandemics. Each chapter briefly describes a fictional, but fact-based, health crisis and what a real-life response would look like.

It’s a difficult book but, says Osterholm — who warned that COVID-19 was a pandemic months before others acknowledged it — it’s never been more urgent.:

Q: Given COVID fatigue, “The Big One” could be a tricky sell. Why this book now?

A: We are going to have more pandemics in the future and, as the book’s title suggests, they could be a lot worse than the one we just had. One of the motivations of writing this book was to provide a story of what happened, what could have happened or didn’t happen and say what were the successes. We never did that.

Q: Meaning that we, as a society, never took stock of our pandemic response? Is that unusual?

A: One of the most amazing things with the post-9/11 commission was that it was bipartisan. No finger-pointing. Identified lots of mistakes and challenges that could have been or should have been addressed before 9/11 ever happened. We learned a lot from that and a lot of that was incorporated into our everyday lives.

Q: The book talks about politicized debate over whether COVID originated in a market in Wuhan, China, or a lab leak. That kind of thing is why we haven’t had a 9/11-like reckoning for COVID?

A: The fact that this one became so politically contentious was a huge challenge. No one wanted to touch a report. I do address the issue of Wuhan in the book and the fact of the matter is we’ll never know. Move on! We have got to be much better prepared for the next pandemic or, for that matter, for seasonal influenza and coronavirus infections.

Q: One section of “The Big One” that may startle readers is when it discusses inadequate masks and other COVID measures you say didn’t do anything.

A: We covered heavily the respiratory protection side because so much of the respiratory protection we did was useless. I still feel badly even today when I see people wearing masks, quote unquote, under their noses. That’s a chin diaper, not a respiratory protection device.

Q: But when we eventually got N95 masks, those helped?

A: Where there was consistent use of N95 masks, protection was remarkable. But a lot of the studies never really measured effective use. Look at the plastic shields at grocery stores. They were useless. We spent millions and millions of dollars doing that, and the 6 feet thing was the same. Useless.

Q: Which hit home for you, right?

A: I think the one time I got exposed I wasn’t wearing an N95 in my own building and that’s when my partner, myself and one of my colleagues all came down with COVID, two days later. The only time we were all together was moving through that building without respiratory protection devices.

Q: You had done a study on a 1991 measles outbreak at the Metrodome that showed infections travel?

A: The virus literally jumped 425 feet from home plate to up in the far, far right field, where even Mark McGwire couldn’t hit a home run on steroids. It bounced literally up there and nailed everyone in the section who wasn’t protected. That’s how infectious these viruses can be. Do you think a plastic shield would have helped?

Q: With the talk about “fake news,” were you worried about the fictional scenario described in “The Big One” before it shifts to real-world events?

A: No. I think it’s almost a playbook for people to understand: “Oh, when we talk about the factual basis of a pandemic, what we’re reading gives a sense of what that will be like.” Communications would be an example. What are the challenges? When you see what unfolds in real time in each chapter, you immediately see the effects of the pandemic.

Q: One frustrating thing during COVID was it felt like we were getting mixed messages and that the rules kept changing. You argue that communication about the virus should have been more candid, so people understood that we just didn’t know.

A: I’m not going to sit here and say I got it right and everyone else got it wrong. But, early on in the pandemic, I recognized that we had to have a real sense of humility about what we knew and didn’t know. And when we didn’t know, we needed to be clear about that.

Q: For example?

A: When we got to the vaccine, I thought, “What evidence do we have that this is going to be a 94% protection vaccine at one year? Be careful.” You can say it provides 94% protection at two months but we’re going to give you information every month about what the level of protection is and if it wanes, we’re going to tell you that and say maybe we need to give you a booster. If we had done that, people would not have felt sticker shock because we said, “This vaccine will protect you” and then it didn’t.

Q: We needed to evolve as the virus did?

A: We needed to say, “This is what is happening now. We’re seeing different transmission now in 2022 than we did in 2020 and that changes our understanding of what’s happening.” That’s what this book is about — trying to help frame those lessons we should have and could have learned.

Q: Because, as the title suggests, the next pandemic could be worse?

A: One of the things that saved us with MERS and SARS was they weren’t as infectious but, on the other hand, killed 25%-30% of the people who got it. COVID killed 1½%. Since I wrote this book, we have uncovered a new virus in China — from a bat in a cave, it wasn’t from a lab — that has the same high-efficiency transmission potential that COVID did. And it has the same genetic characteristics as a MERS or SARS that could kill 30% of the people infected. That’s floating out there right now. That, tomorrow, could be the next pandemic.

Q: So preparedness, particularly in the area of vaccines, will be more crucial, even as your book notes the current government is skeptical of, for instance, vaccines. What can we do?

A: This is the collective will of the people. What we need to have happen is a general understanding of why we need to be better prepared. Do you think there will be better preparedness for a flooding of the Guadalupe River in the future? I think so. We need to have the mindset that it’s going to cost us to do this but it’s an incredible insurance policy for society.

The Big One: How We Must Prepare for Future Deadly Pandemics

By: Michael T. Osterholm and Mark Olshaker.

Publisher: Little, Brown, 357 pages.

©2025 The Minnesota Star Tribune. Visit at startribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments