Michael Phillips: In 'Cinema Her Way,' female directors talk about struggle, survival and the industry

Published in Books News

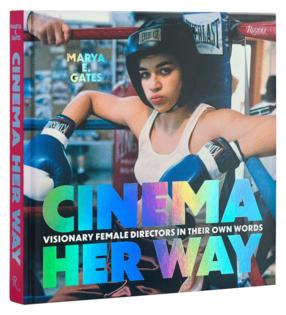

Just published by Rizzoli New York, “Cinema Her Way: Visionary Female Directors in Their Own Words” is a beautiful 20-way conversation on the topic of filmmakers whose often brilliant careers did not and do not come easily. The reasons for that have everything to do with the words “her” and “female” in the book’s title.

The Chicago-based writer and critic Marya E. Gates wrote it, bringing a terrifically inquisitive and expansive authorial voice to this collection of interviews, 19 in all. Working independently or on the slippery sands of the late 20th and early 21st century Hollywood system, Gates’ subjects have made features of every kind, across nearly half of film history. Framed by bold, sharp graphic designs and illustrations by Alex Kittle, the book serves as a rich chronicle of accomplishment and an argument for more equitable access to the business of making movies. It’s ridiculous that the same argument needs relitigating in 2025.

Gates writes for rogerebert.com and many other publications, and earlier worked for Turner Classic Movies as well as its short-lived streaming service Filmstruck. She moved to Netflix and soon started freelancing. On her Substack, “Cool People Have Feelings, Too,” Gates posts her weekly “Directed by Women Viewing Guide.”

For “Cinema Her Way,” Gates conducted interviews between 2022 and 2024. Her roster included the woman behind her favorite film: Australian director Gillian Armstrong, who made the 1994 “Little Women” that Gates remembers seeing with her mother when the author was 8. A formidable close-up of then-unknown actress Michelle Rodriguez, from director Karyn Kusama’s 2000 feature debut “Girlfight,” graces the book’s cover.

Gates’ introduction includes a chapter titled “In the Beginning,” a deft encapsulation of the filmmaking period preceding the generations represented by the women showcased in “Cinema Her Way.” The prologue includes the crucial first step taken by Alice Guy-Blaché, who worked with the Lumière Brothers in the silent days, made her own films (uncredited), became a popular invisible filmmaker, relocated to America, ran a studio, slid into obscurity, and only in recent decades reclaimed her remarkable place in film history, albeit posthumously. Gates and other silent film scholars contend, convincingly, that Guy-Plaché was responsible for the first narrative screen storytelling.

Which means, as Gates writes in her book, that “the original film grammar was created by a woman, and that cinema has always been her way.” The following conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Q: You write in your introduction that Alice Guy-Blaché was the primary inventor of what we know as narrative filmmaking. Can you expand on that for those who don’t yet know about her?

A: A lot of scholars agree that the earliest extant narrative film is her film “The Cabbage Fairy.” Her original 1896 version no longer exists. She remade it three times; the one we have is the second version from 1902. You can find it on YouTube.

Essentially Guy-Plaché was an assistant with the Lumière Brothers, and she was tired of helping them do their thing (laughs). And she was, like, can I film some stuff? And they were, like, I mean, I guess … so they gave her a camera and she started filming. She had this idea for “The Cabbage Fairy,” she made it, people loved it, she started making more. Very simple narratives. But they did very well for the company. And she didn’t get credit. It took until the 1970s for scholars to attribute her work to her.

She probably made 600 to 700 films. And she appears to have been the first director to prove you don’t need to simply use a camera to stand there and watch people. You can actually use the camera to tell a story in front of it.

Q: Reading these interviews with so many filmmakers in your book, the challenges facing these women, they’re inspiring and and crazy-making in equal measure.

A: Yeah. That’s about right. It was inspiring-slash-depressing to realize Gillian Armstrong (“My Brilliant Career”), who began in the ‘70s, had so much to say about how hard it was starting out as a woman. (In interviews) she just wanted to talk about being a filmmaker, but she had to keep talking about what it was like to be a woman, you know. Then, when I talked to Josephine Decker, who started making films 15 years ago, she told me she had the same experience. And I thought, Oh no. That’s not good. They shouldn’t have the same hurdles!

Q: I loved learning about your filmmakers’ early influences, which are all over the place. Nobody grows up liking only one kind of film. One credits the juicy drive-in movies made by Roger Corman —

A: — And two different directors mentioned the impact of “Benji,” from 1974! Which I didn’t realize was an inspirational film.

Q: Huge success. I don’t love animals-in-peril movies, but —

A: That’s probably why I haven’t watched it. I saw “Old Yeller” when I was 8 and that was that.

Q: Where did you grow up?

A: Alturas, an hour south of Oregon, two and a half hours west of Nevada. My hometown has 2,500 people. My dad grew up in the San Fernando Valley and was really into movies. Growing up in the ’90s, during the video store boom, at one time we had four video stores in our town. I watched (every) week. For years.

Q: Anything in particular, or just everything?

A: I watched “Muriel’s Wedding” a lot. When I was really little I rented “Ernest Scared Stupid” to the point where my mom said, “You can’t rent it anymore. I don’t want to see it again.” (laughs) I watched “The Englishman Who Went Up a Hill and Came Down a Mountain” because I liked Hugh Grant. I rented a lot of things just for the actors. That’s why I saw “The Thin Red Line” (Terrence Malick’s hypnotic World War II reverie). I was really into “ER” and George Clooney was in “The Thin Red Line,” but it was a 30-second scene. So I went up that hill wanting to see George Clooney and came down a cinephile.

Q: In the end, what did you learn from all these conversations? Something that might be related to film, but maybe connected to a larger issue?

A: The main thing I learned from all these women was simple: You have to have a team. You need people you trust in your life. Especially in the arts, everything is hard, and if you don’t have someone who’s your cheerleader, someone to fight the fight with you, it’s very lonely. Some of the women I talked to are true loners, and it’s harder if you’re a lone wolf and you don’t really want to fight the fight with other people.

Either way, you have to have the confidence in yourself. But I think having someone to re-assert your own confidence is important. The main connection through all the interviews is just that you can’t do it alone. Filmmaking depends on a solo vision, but you need a team to help you creatively, financially, every way. Anything to make it a little easier.

_____________

©2025 Chicago Tribune. Visit chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments