'We are time's subjects': Author Clock keeps track of the hours, one literary quotation at a time

Published in Books News

The Author Clock, created in Chicago several years ago by a local engineer and finally arriving in stores this holiday season, has been forcing me to pause now and then, whenever I look up to see the time. Knowing the time used to be fast for me. But the Author Clock slows one’s relationship to time. I don’t know yet how I feel about it as a daily timepiece, but I can say for sure, that it is not a clock to take for granted. Even the coolest Swatch or vintage Mickey Mouse, after some admiring, gets taken for granted.

Not so with this.

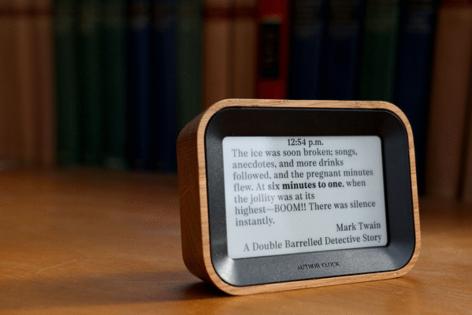

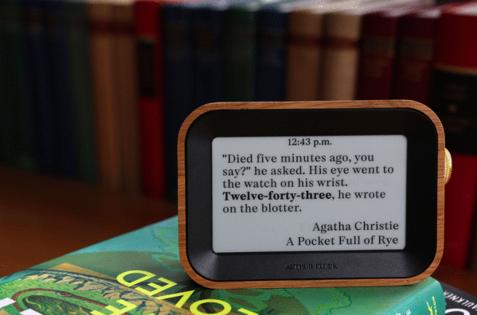

The Author Clock is small and rectangular and housed inside a wooden frame. Its clock face is Kindle gray, and instead of a traditional number-based digital readout or circular timepiece, it shows a quotation from a book containing the exact time of day. The other day, for instance, at exactly 11:32 a.m., the Author Clock informed me that, in James Joyce’s infamously rambling “Finnegans Wake,” there is a character named Marcus Lyons who poetically remembers:“Flemish armada, all scattered, and all officially drowned, there and then, on a lovely morning, after the universal flood, at about eleven thirty-two.”

At 11:35 a.m., it read, courtesy of a passage from the Robert Harris thriller “Munich”:“The Prime Minister’s plane came to a stop at Oberwiesenfeld airport, at 11:35 a.m.”

At precisely noon, Dr. Seuss himself informed me: “And by noon, poor old Horton, more dead than alive, had picked, searched and piled up, nine thousand and five.”

For the practical person, the bold-faced time will be what matters in each passage on the Author Clock, which pairs every minute of the day with thousands of quotations that reference every minute of the day. Its creators, engineer Jose Cardona, designer Luke Gray and editor Yasmin Sara Gruss, partly dug up and partly crowd-sourced 13,193 book passages that refer to specific minutes, then arranged them digitally into the 1,440 minutes that make up 24 hours. Author Clock comes loaded with those 13,000-odd lines; Wi-Fi updates add more. Because there are so many more than 1,410 quotations, it also rarely gives the same passage at the same time two days in a row.

So, now, when I sit at my desk, time is no longer a relentless progress of numbers but a string of random experiences — which, I suppose, is what we often hope to take away from time. One day, at 4:15 p.m., my Author Clock read:“The sun had begun to sink in the west, and the shadow of an oak branch has crept across my knees. My watch said it was 4:15.” That’s from Haruki Murakami’s “The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle.” At 12:45 a.m.:“It is twelve forty-five. Time for my dwindling medication,” as Deborah Levy wrote in “Hot Milk.” At 10:38 a.m., Charles Dickens even noted the way in which we take for granted ordinary clock design:“‘It’ll be done to a turn,’ said the landlord looking up to the clock — and the very clock had a colour in its fat white face, and looked a clock for jolly Sandboys to consult — ‘it’ll be done to a turn at twenty-two minutes before eleven.’”

This thing is so strange and paradigm shifting, I had to know more.

The concept came to Cardona when he worked as a product-design consultant in the West Loop. He made samples at mHUb on West Fulton Street, a local testing ground for prototype development and magnet for venture capitalists. Cardona adds that the idea for a literary clock wasn’t his alone, then he winds through a history of inspiration:

First, there was the artist Christian Marclay’s remarkable 2010 installation “The Clock,” a 24-hour long film constructed out of thousands of scenes edited together from thousands of movies, arranged so that when you watching “The Clock” at, say, 2:30 p.m., it’s 2:30 p.m. in the movie clip on screen. (Its most recent Midwest exhibition was in 2014 at Minneapolis’s Walker Art Center; since it requires a gallery to stay open 24 hours a day, there has not been a Chicago showing.) Marclay’s work made such a splash (it won the Golden Lion at the 2011 Venice Biennale), it inspired the book staff at London’s Guardian newspaper to attempt something similar using literary passages.

That led to a tech designer in the Hague, using the Guardian’s quotations, assembling a literary clock on a hacked e-reader. He posted instructions online for creating your own clock — which led to a Danish coder creating a literary-clock website (literature-clock.jenevoldsen.com). About this time, Cardona, who had recently graduated college with an engineering degree, was looking for a product to make. “I was an avid reader, I heard about the clocks, I knew someone would absolutely make it as a product. That was six, seven years ago. I’d occasionally check to see if anyone made it yet.” When no one did, Cardona jumped in. Gray, who has worked on many household products as a designer (for Ikea among others), came up with the minimalistic look; Gruss, a freelance editor who taught literature courses at Brooklyn College, began evaluating every quotation.

To fund its development costs, Cardona turned to Kickstarter and Indiegogo. He sought to raise a relatively modest $20,000; he ended up netting more than $2 million.

He’s since left Chicago and moved back to his native Puerto Rico. About four years later, the Author Clock is now sold in museum shops and book stores; it’s also being offered through AuthorClock.Com. Cardona said he’s sold about 20,000 so far: “We can’t make them fast enough.” The desk size is $199; a larger hangable one is $349.

Both do the same thing. That is, one minute at a time, they offer a kind of history of literature — or rather, a history of how authors have used timepieces as a literary device.

“Initially we wondered if authors even mention time often enough to serve a clock like this,” Cardona said. “Turns out, they do. But it wasn’t always the case. People didn’t live so minute-by-minute until relatively recently.” Reliable, consistent timepieces emerged in the late 19th centuries, and wristwatches didn’t take off with the public until about a century ago. The oldest quotes in the Author Clock date to “The Canterbury Tales” in the 14th century but the majority come from the past 100 years of fiction. “We particularly noticed an uptick in writers using time as detective characters got popular in the 1920s.”

What I’ve noticed about the Author Clock is how we use time to memorialize an instant — to recognize the flat tick of the everyday. Or we need to note the urgency to beat time: Harry Potter racing to his train at 10:45 a.m., Jack Reacher retrieving his assault rifle at precisely 11:34 a.m., Dean Moriarty in “On the Road” promising to return by 3:14 p.m.

Cardona and Co., buoyed by the success of the Author Clock, are already working on a home weather station that uses literary quotations about the weather to provide a local forecast. Weather is often an author’s proxy for establishing an emotional state, he said.

Time, however practical, is more elastic. The Author Clock illustrates how it means something different to everyone. All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us — as Gandalf tells Frodo. He says this “after a late breakfast,” Tolkien writes.

But he doesn’t mention the exact time.

©2024 Chicago Tribune. Visit at chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments