Column: Andrew Davis gave us 'The Fugitive,' now he brings forth a novel, 'Disturbing the Bones'

Published in Books News

Andrew Davis, Chicago to his core, was telling me a couple of days ago, “I am a visualist, not a wordsmith,’’ but he was selling himself short.

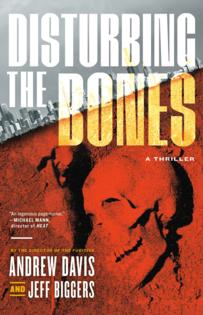

Though he is rightly acclaimed for his “visual” accomplishments, which include directing a bunch of successful movies, especially “The Fugitive,” I was holding in my hands a book “Disturbing the Bones,” and on its cover was his name, along with that of co-author Jeff Biggers.

“Yes, I wrote the book, a novel,” he said. “Wrote it with Jeff and with much work. It was new to me but I did start out by studying journalism in college, you know, and I have written some screenplays. But a novel is a very different thing. Yes, it was challenging but a creative joy. I hope people like it.”

He wears those modest insecurities lightly, because there has been much advance excitement and praise for the book, such as this from our own master of crime fiction, Sara Paretsky: “Andy Davis fans will find everything in this story they expect from the creator of ‘The Fugitive’ — a high-voltage thriller, an amazing range of characters, and an astonishing conclusion.”

Michael Mann, another Chicagoan and famous filmmaker (“Thief,” “Manhunter,” “Heat,” and, most recently, “Ferrari”) who recently dove into the the literary fiction world with his “Heat 2,” written with Meg Gardiner, calls this book “a knife-edged investigation that morphs into a political thriller about a world on the brink.”

It was born in Chicago a decade ago, when Davis met Biggers in the back room of the Heartland Cafe for a taping of the radio show “Live From the Heartland,” hosted by Michael James, Thom Clark and Katy Hogan.

Biggers, a historian and investigative journalist, was on the show to talk about his then-new book, “Reckoning at Eagle Creek,” which the Sun-Times called, “an insightful project blending Biggers’ personal connections to his southern Illinois roots with a cutting analysis of the staggering human and environmental cost of coal mining.”

Fortuitously, Davis was also a guest. “I was impressed with and liked Jeff,” he says. “I immediately read his book and realized what a tremendous understanding he had of this area, of race relations, of humanity.”

The two men, Davis mostly from his home in Santa Barbara, California, and Biggers from places around the country, began to collaborate on what they initially intended to be a screenplay. “We kept feeling the need to build backstories for the characters,” Davis says. “As that happened it began to feel to both of us that what we had was not a movie but a novel and we plowed ahead.”

It is a novel that begins at an archaeological dig in southern Illinois, travels the globe and contains some of the themes — geopolitics, nuclear disarmament and murder among them — that have peppered Davis’ films.

It features many compelling characters, principal among them Molly Moore, a young archeologist who makes a mysterious skeletal discovery on a downstate dig; Randall Jenkins, a veteran Chicago police detective haunted by his mother, who went missing downstate years before; and a retired general named William Alexander, whose motives are less than healthy or honest.

Events move swiftly, under the increasingly ominous shadow of global disaster.

“There is a cinematic quality to it,” he says. “I see it in pictures.”

Davis is coming home this week for a series of events to promote his book, part of an extensive national tour. He will try to visit some old pals and relatives.

As with most any conversation with Davis, ours drifted pleasantly back in time. He was born in 1946 on the West Side, spent his early childhood in Rogers Park and then moved to the Southeast Side.

His parents were Nathan and Metta Davis, lovely people who met when they were with the Chicago Repertory Group, an experimental theater company. She would go on to become a schoolteacher and he would become a pharmaceutical sales representative as well as an esteemed actor in film and on stage.

Andy was president of his YMCA photographic club at age 8 and a grammar school movie projectionist, played guitar in local bands, and was a journalism student at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign before the movie business. He made his directorial debut in 1978 with the critically acclaimed independent musical “Stony Island,” which he also co-wrote and produced.

He and his wife Adrianne moved to Santa Barbara and other movies followed, boosting him onto the industry’s A-list of directors, allowing him to shoot many of his movies here.

“Chicago,” he has ever told me, “has always been my cinematic playground.”

We talked a bit about some of his cinematic projects, such as “a modern retelling of ‘Treasure Island,’ set in post-Katrina Louisiana.”

But the movie business is a crazy business these days, increasingly focused on what Martin Scorsese and others lament as Hollywood’s reliance on film franchises. I asked him about what he made of the news that Mann was making a sequel to his 1995 film “Heat,” already working on writing the screenplay based on his novel “Heat 2.”

There was a pause before Davis said, “That’s interesting.”

Though he was speaking by phone from California I could almost see him smile.

©2024 Chicago Tribune. Visit at chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments