Hurricane season is a wrap. What kept storms away from Florida and the US?

Published in News & Features

MIAMI — For the first time in a decade, every single state, including the storm magnet of Florida, escaped the entire hurricane season without a direct hit from a hurricane.

Meteorologists say we owe this good fortune to an unusual weather pattern that steered nearly every storm away, a rare phenomenon of two hurricanes merging and some dumb luck — at least for the U.S. Jamaica, raked by record-setting Hurricane Melissa, was not so lucky.

“Every year is a lovely year not to be hit by a hurricane. We deserved a break,” said Jeff Berardelli, chief meteorologist and climate specialist at WFLA Tampa Bay.

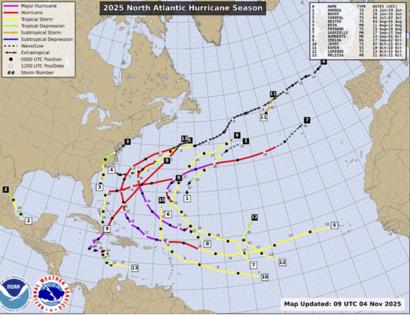

Hurricane season officially ends Nov. 30, and although forecasters originally called for an above-average season, it ended up closer to an average season and none of the five hurricanes that formed in the last few months touched U.S. soil.

Of the 13 total named storms this season, one of them did brush the coast of South Carolina with some heavy rains in July: Tropical Storm Chantal. The impacts were relatively minor.

The Caribbean, unfortunately, underlined the rule about hurricanes: All it takes is one. Hurricane Melissa roared into the region in late October as one of the most formidable storms on record. Around 100 people died, about half in Jamaica and half in Haiti, which was deluged with record-setting rain and floods.

Scientists are still analyzing the storm, but initial data suggest it was tied with the Labor Day Hurricane of 1935 for strongest land-falling storm in the Atlantic. Melissa was also one of three Category 5 hurricanes this season. Only 2005 had more Category 5 storms in one season, with four in total.

Steering storms away from the U.S.

And yet, despite the intense and at times record-setting hurricanes whirling around in the Atlantic basin, they mostly kept to a similar pattern, curving away from the U.S. coast and toward the island nation of Bermuda.

It was, as Berardelli puts it, a “Bermuda year.” Only one hurricane — Imelda — actually crossed the island, but several came close.

That’s thanks to a big push of low pressure air over the continental U.S. that remained in place for most of the season, said Brian McNoldy, a senior research associate at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric and Earth Science. This feature, also known as a trough, pretty much sat over the U.S. from August through October — the peak of the season.

“That induced anomalous counter-clockwise steering winds around it which helped to direct approaching storms to the north well before they reached the U.S.,” he said.

Scientists had a hunch that this might be the case before the season even kicked off. Early season forecast predictions, in April, suggested that it might be a season with lower than usual activity in the Gulf and Caribbean. And it was, with the exception of Melissa at the end.

Compare that to 2024, when early season predictions suggested more activity than usual in the Gulf and Caribbean. Last year the region was smacked with three hurricanes, Debby, Helene and Milton.

“I think it’s a nod to seasonal forecasting being pretty darn accurate,” Berardelli said. “I don’t think this is coincidence. I think we’re getting much better.”

Another factor that kept the U.S. coast free from hurricanes this year was a rare event in the meteorological universe — the Fujiwhara effect.

Also called binary interaction, it’s what happens when two storms interact in some way. In this case, Hurricanes Imelda and Humberto were both carving through the Atlantic at the same time when the stronger storm, Humberto, drew in the weaker storm.

“There was ALMOST a U.S. hurricane landfall (Imelda), but Hurricane Humberto was in the right place at the right time to induce a Fujiwhara interaction which tugged Imelda away from the U.S. before it got too close to the coast,” McNoldy said.

Fingerprints of climate change

Despite the odd season, the National Hurricane Center’s preliminary verification report for the season found that its forecasters did a pretty good job of predicting what storms would do. Data showed that this year’s crop of storms was about 50% harder to predict than usual, the center said.

And yet, “2025 was one of the most skillful years of intensity forecasting for NHC,” the center’s report read.

One of the reasons it was harder to forecast this year’s storms was just how many of them rapidly intensified, a process where a storm gets much, much faster over a short window of time. Hurricanes Erin, Humberto and Melissa all rapidly intensified this year, partially thanks to the much warmer than usual waters of the Atlantic and Caribbean.

Hurricane Erin broke records for the earliest Category 5 outside of the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico. Last year, Hurricane Beryl became the earliest Category 5 on record.

Hurricane Melissa, at the tail end of the season, rapidly intensified while remaining virtually motionless over a pool of near record breaking warm water.

“Had this stall happened almost anywhere else, the storm would have upwelled cooler water from below and weakened, but it was parked over very warm and very deep water for a virtually endless fuel source,” McNoldy wrote in his year-end blog post about the season.

That warmer than usual water is a product of a hotter world affected by climate change, scientists say. Several rapid studies after Melissa made landfall all found something similar: that the hotter ocean and human-caused impacts of global warming likely made Melissa stronger, faster and more deadly.

That makes Melissa the latest real-world example of what research has suggested for years about how climate change will impact hurricanes, Berardelli said.

“I think we are entering a slightly different era now, with hurricanes achieving milestones that were possible but more difficult in decades past,” he said. “We shouldn’t be surprised any more by surprises.”

©2025 Miami Herald. Visit at miamiherald.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments