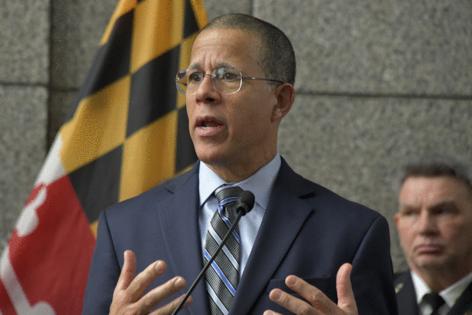

Anthony Brown's ICE guidance won't impact police partnerships, officials say

Published in News & Features

Maryland sheriffs call it a political stunt, while legal experts say State Attorney General Anthony Brown’s Wednesday guidance was meant to ease concern, not to impact current or future partnerships between local agencies and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement [ICE].

On Wednesday afternoon, Brown sent out a memo as a reminder that Maryland law restricts how local and state law enforcement agencies can interact with federal agents. Specifically in this case, he made it clear “while performing regular police functions, Maryland officers may not enforce civil immigration laws or assist federal agents in enforcing such laws.”

Guidance like this from an attorney general is meant for two audiences, said Cori Alonso-Yoder. She works as both the Director of the Immigration Clinic and as an Assistant Professor at the University of Maryland School of Law.

“This should be the operating order for Maryland police, for those on the ground,” Alonso-Yoder said. “[But] the guidance is not just for the police. There is a healthy concern that people who are witnesses, people who are victims will not come forward, out of fear of being detained.”

Details like this, Alonso-Yoder said, are meant to help the community understand what is and isn’t allowed, so alleviate some of that fear when it comes to local law enforcement. It’s also meant as a reminder to agencies.

A different way of seeing it

Maryland sheriffs see it a different way.

“I’ve been in law enforcement for 41 years, never have I needed guidance from anyone, let alone Maryland’s Attorney General, on the requirements of Maryland law enforcement when working with federal law enforcement agencies,” said Wicomico County Sheriff Mike Lewis. “What frustrates me is this is not the first cautionary guidance we’ve received on this very same issue from the Attorney General’s Office, and we sheriffs and we chiefs believe that they’re sending it out for no other reason reason than to intimidate us and hope that we’re gonna stand down.”

Back in January, Brown issued guidance that local agencies couldn’t share personal information with ICE without a warrant, must not extend detentions to investigate a person’s immigration status and are prohibited from contracting with private immigration detention facilities. At the time, Brown also cautioned that agencies and individual officers can’t ask about a person’s immigration status unless it’s relevant to a criminal case.

Lewis said he knows state law and didn’t need a reminder. If Brown wanted to alleviate concerns, that could have been a press release, rather than guidance directed to the agencies.

“We’ve been well aware of what we can and cannot do,” Lewis said. “But they’re trying to intimidate us and trying to coerce us into not cooperating with the federal government.”

Wicomico has discussed signing a partnership agreement with ICE, with a proposal expected to come before the county council in November. Nothing Brown said on Wednesday will change that, Lewis said.

In Harford County, Sheriff Jeffrey Gahler gave a similar answer. Harford is one of eight counties currently operating with an ICE partnership in Maryland. The others are Alleghany, Carroll, Cecil, Frederick, Garrett, St. Mary’s and Washington. Gahler argued the guidance doesn’t affect his department, as their partnership is jail-based.

“All individuals who are arrested for committing crimes in our community, are screened after they are booked into the Harford County Detention Center,” Gahler said. “If they are found to be in the Country illegally, that information is shared to ICE, who will make a deportation determination based on their priorities of public safety and national security. The program fully complies with Maryland law, and nothing in the Attorney General’s guidance impacts this important public safety partnership.”

Gahler added the guidance comes across more like a political publication than a practical directive.

“My concern is that it could be misinterpreted in a way that discourages law enforcement from sending aid to federal partners during real criminal emergencies, such as the assaults on federal officers and other acts of violence we have witnessed across the United States,” Gahler said.

Beyond the task force model, which isn’t used in Maryland, there are two types of ICE partnerships with law enforcement. The Warrant Service Officer model allows local officers to serve existing federal warrants. The Jail Enforcement model, which Harford uses, pays for training so corrections officers can check the immigration status of suspects in local jails. These partnerships are voluntary, with counties and cities able to approve or reject them as desired.

Cecil County Sheriff Scott Adams, whose department uses the Warrant Service Officer model, said the guidance wouldn’t affect their partnership either. He agreed with the other sheriffs as to the political nature of the document.

Baltimore County officials said they’re still reading through the document.

“The Department is in the process of fully reviewing the AG guidance in order to ensure that our policies comply with all applicable laws,” Baltimore County Police Spokesman Trae Corbin said.

Does guidance impact partnership?

Alonso-Yoder says guidance like this does not impact current Maryland partnerships, because those aren’t dealing with law enforcement. Both models used in the state involve people who have already been arrested, charged and are in the local jail.

“It’s saying there should not be on the ground [immigration] enforcement from police,” Alonso-Yoder said. “But the partnerships are about people who have already been booked.”

It’s a much less restrictive version of the policy employed by Prince George’s County. In 2019, the county council voted to ban police and other agencies from working with ICE. The only exemption is for any serious criminal issues.

The Baltimore Sun reached out to Brown’s office multiple times over the last two days. To date, we have yet to receive a response.

Currently, 21 states have either publicly refused to work with ICE or taken legal action against the agency. In January, Brown, along with 12 other attorneys general from California, Colorado, Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois, Minnesota, New Mexico, New York, Rhode Island, Vermont and Washington, issued a joint statement, arguing the Constitution prevented federal officials from forcing states to enforce federal laws.

Over the course of this year, the federal government has filed lawsuits against states and cities whose policies are seen as obstructing immigration enforcement. Federal officials have also threatened to take away grant funding in some cases, from states that don’t comply with ICE.

That last part is allowed. In a 2019 Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals case, the court upheld the U.S. Department of Justice’s ability to give preferential treatment to cities that cooperate with federal immigration authorities when handing out law-enforcement grants, as that was found to be germane with enhancing public safety.

_________

©2025 The Baltimore Sun. Visit at baltimoresun.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments