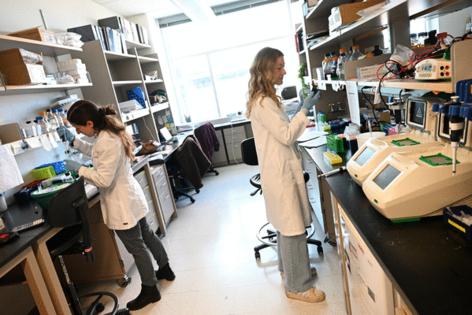

Blood test may detect who will get rheumatoid arthritis, study finds

Published in News & Features

DENVER — People who develop rheumatoid arthritis experience changes to their immune systems long before their joints become swollen and painful, suggesting that early treatment might stop or limit damage, a new University of Colorado study found.

Unlike typical osteoarthritis, where cartilage in joints breaks down, rheumatoid arthritis results from the immune system attacking healthy tissues. The main treatments suppress parts of the immune system, leaving patients more vulnerable to infections.

Dr. Kevin Deane, director of the Autoimmune Disease Prevention Center on CU’s Anschutz Medical Campus, said a study following patients at risk for rheumatoid arthritis for seven years found a consistent pattern: The participants all had one type of antibody against their own tissues, which gave them about a 30% risk of going on to develop rheumatoid arthritis.

Antibodies are supposed to flag infections, so the immune system can destroy the invader. People who developed the disease had other changes that would show up on a blood test, meaning that early screening for rheumatoid arthritis could be feasible in the future, he said.

About 1% to 2% of people have the first antibody, indicating they could be at high risk and might benefit from further monitoring, Deane said. A second study, currently enrolling on the Anschutz campus, will follow people with that particular antibody for five years, to test preventive measures.

People who might be at higher risk because a relative has rheumatoid arthritis can get tested for the antibody to see if they’re eligible.

Right now, the only prevention options for people at risk of rheumatoid arthritis are lifestyle changes, such as quitting smoking, exercising and eating a healthy diet, Deane said. With more understanding of the underlying changes in the immune system, researchers can start testing whether other treatments could prevent or delay rheumatoid arthritis, or lead to less-severe symptoms when it eventually develops, he said.

As is, about 70% of people with rheumatoid arthritis need more than one drug to get it under control, Deane said. Hopefully, if they can start treating the disease before it causes joint damage, patients can take fewer drugs and avoid some side effects, he said.

The idea has precedent: Children at risk for type 1 diabetes can now take a medication to delay damage to their pancreases, though it doesn’t entirely stop the disease process.

If they can study the right antibodies, researchers could also discover and possibly delay the changes leading to other autoimmune diseases, such as lupus and celiac disease, Deane said.

While stopping a disease altogether would be ideal, “that would also be a victory,” he said.

---------------

©2025 MediaNews Group, Inc. Visit at denverpost.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments