China's lone-wolf attacks pose challenge for Xi's security state

Published in News & Features

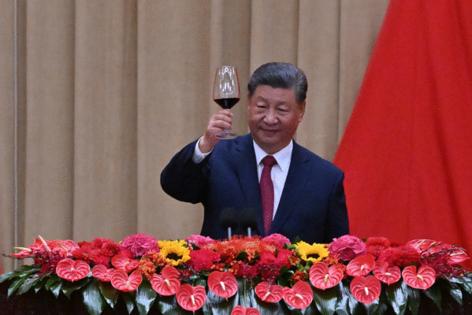

President Xi Jinping has built a sprawling security system to prevent violent forces from destabilizing society. A new wave of deadly attacks is putting pressure on officials to expand that surveillance state.

China was stunned this month by its deadliest act of public violence since a string of terrorism strikes rocked the remote Xinjiang region in 2014. Dozens were hospitalized and 35 killed by the bloody car-ramming in Zhuhai city that was the culmination of a spate of violence this year — mostly stabbings — which have sparked nationwide anxiety.

Xi responded to spouts of ethnic violence a decade ago by installing a network of facial recognition cameras, tightening internet controls and expanding a national resident database. Now, the ruling Communist Party is calling on its army of local officials to weed out would-be attackers, drawing on the nation’s troves of big data for that mission.

Scattered lone-wolf attacks will likely prove hard to contain, even for the all-seeing Communist Party. The assailants don’t hail from a single group or have a unified cause. While some have pointed to low pay and property woes as their motivation, there’s no quick fix for economic problems leaders have been battling for years.

Showing the urgency of the problem, Xi ordered officials up and down the nation to prevent such violence shortly after the Zhuhai attack. “Resolve conflicts and disputes in a timely manner,” he instructed apparatchiks. “Strictly prevent extreme cases, and do your best to protect the lives of the people and social stability.”

For decades, Chinese leaders have held their grip on power through an unspoken grand bargain: Citizens sacrifice some freedoms in exchange for security and prosperity. The recent fatal outbursts come as officials also struggle to deliver greater wealth, with the economy battling its longest deflationary streak since 1999 and a yearslong property crisis wiping billions of dollars off households’ books.

While the Chinese government has spent years pointing to mass violence in America as proof of the inferior U.S. system, stepping up domestic surveillance carries its own risks.

Xi’s COVID Zero regime — which imposed long quarantines, regular mass testing and strict curbs on movement — exposed the limits of citizens’ tolerance for state overreach. That policy crumbled in late 2022 after nationwide protests that, at times, called for the downfall of the top leader.

Chinese society is “fed-up and angry with a bunch of issues,” said Lynette Ong, professor of Chinese politics at the University of Toronto. “Unless the leadership comes to the realization that you need to go to the root cause of the problem — which is letting people release their pressure and anger and having more pressure valves — doing more repression actually will not work.”

Chinese officials in recent weeks have rushed to reinforce Xi’s security message. Anti-corruption chief Li Xi told local governments to “take practical measures to consolidate the party’s ruling foundation” by resolving grassroots problems. Graft busters should make that their priority when inspecting villages, he added.

Ramping up tech surveillance would require more resources at a time when public finances are tight. Government spending on security — with the bulk coming from indebted localities — only grew by 3.1% last year, the lowest during the Xi era excluding the pandemic, according to China’s latest statistics yearbook.

Policymakers are instead focusing fiscal policy on stabilizing the housing crash, and a $1.4 trillion plan to rebalance struggling local governments’ books. Top leaders are now preparing for next month’s Central Economic Work Conference, where they’ll map out economic priorities for 2025 when U.S. President-elect Donald Trump returns to office.

One less costly tool officials are leaning on is the “Fengqiao experience:” A Mao Zedong-era surveillance campaign used last century to root out anti-party forces, that Xi has revived in recent years to prevent local disputes and disruptive groups from bubbling up to the national level.

Already officials in Dingxi city, in China’s northwest, are conducting visits to the families of those who are deemed to have lost hope in life and displaying abnormal behavior along with paranoia, according to an official police WeChat account. Local leaders will try to educate and counsel the needy, it added.

Prosecutors in a Guangdong city have now started prioritizing clearing a backlog of cases related to residents’ unhappiness with the judicial process to prevent frustration from spilling over, according to a person familiar with the issue who asked not to be identified discussing sensitive matters.

Authorities will utilize existing technology in their push. Officials should mine the “rich” well of legal data to find people who pose a risk, Yin Bai, secretary-general of the party commission in charge of law enforcement agencies, said in eastern Zhejiang recently. He also advocated for strengthening “data identification, screening, analysis and evaluation” to stop attacks.

Schools have emerged as a focus, with several attacks this year targeting students. Police officers have been enlisted to oversee school opening and closing hours in the southern province of Guangdong, according to a person familiar with the arrangement, who requested anonymity.

In Beijing, where a slashing incident near a primary school injured three children last month, another school has increased its number of guards and armed them with new anti-riot steel forks and batons, according to a person familiar with that set-up.

A kindergarten in Shanghai that previously allowed parents to walk their children to the classroom stopped that arrangement this month, citing “multiple vicious incidents that happened consecutively” and a need to “implement instructions from the higher authorities about school safety,” according to a notice seen by Bloomberg.

For a nation where violent outbursts are considered rare, such measures are a significant departure. But to many residents, the extra precautions suddenly seem necessary.

“I hope that the overall security of the school could be ramped up more,” said Vikki Shu, a 40-year-old mother in Shanghai. “When the economy is not stable, there are a lot of crazy people.”

(Jing Li, Daniela Wei and Rebecca Choong Wilkins contributed.)

©2024 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments