How interest rates work

Will they or won’t they cut interest rates in September? All eyes are on the Federal Reserve and its chairman, Jerome Powell. He is seen as the all-powerful Wizard of Rates, but there’s more to the interest rate market than just one man. The buyers of our national debt — our IOUs — have a big say in what happens to interest rates.

The U.S. national debt now stands at more than $37 trillion. We (the taxpayers) will pay about $952 billion in interest on our national debt in 2025. That’s up 8% from last year. And it totals more than 18% of all federal revenues collected this year.

Those are MEGO numbers. That stands for My Eyes Glaze Over! But don’t look away. If we didn’t owe so much money — borrowed by selling Treasury bills, notes and bonds — we could put that money to much better use, or allow people to pay less in taxes and keep the money for their own purposes.

Yet, every week the Treasury sells new T-bills to replace old, maturing ones. T-bills have maturities of one year or less, while Treasury notes have original maturities of 2-10 years, and longer-term IOUs are called Treasury bonds. The latter are sold at monthly auctions.

As these securities mature, the money must be re-borrowed again — at current interest rates. And, of course, the Treasury must sell additional bills, notes and bonds to cover our current annual deficit.

Treasury bill auctions are held weekly on Mondays, with the rates being set by the huge institutional buyers who decide on the interest rate they will require to be willing to lend money to our government. T-bills are considered the safest and most liquid investment in the world, since they are backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government.

And therein lies the potential problem. If bond buyers from around the world lose faith in our government’s ability to repay the debt or in the buying power of the dollars they receive at maturity, they demand a higher interest rate to compensate for those perceived risks.

Every increase in interest rates adds to our annual interest bill, but when rates fall, the government saves on interest.

That long explanation about the bond market should make you think twice about exactly how the Fed can “control” interest rates. Yes, the Fed’s Open Market Committee sets the federal funds rate — the target rate at which banks and credit unions lend reserves to each other overnight. That rate directly impacts borrowing rates throughout the economy.

The Fed also sets the interest it pays banks for holding reserves at the Fed, which helps set the floor for the federal funds rate. And they set the discount rate — the rate at which banks can borrow funds directly from the Federal Reserve’s discount window.

It’s a complex mechanism — but these rates all have one thing in common: they are short-term rates. They are meant to serve as guide rails for economic activity. Higher rates set by the Fed are meant to spread through the economy, slowing economic activity — and fighting inflation. Lower short-term rates are meant to spur investment and job creation.

But just because the Fed can change its short-term rates, there is no fixed correlation to longer-term rates. In fact, the last time the Fed cut short-term rates several times in the fall of 2024, rates in the bond market went UP instead of down. Global bond buyers feared those low short-term rates would lead to the return of inflation. So they demanded higher yields to buy 10-year Treasury bonds.

Since mortgage rates are tied directly to the 10-year Treasury rate, mortgage rates actually went UP one full percentage point in the Fall of 2024 — from 6.1% in September to 7.14% in December 2024 after the Fed’s last rate cut. And they have stayed high ever since, with only a small decline recently.

The impact of a Fed short-term rate cut depends on whether the market views it as a sign of a coming economic slowdown, or whether bond-buyers feel a rate cut will trigger easy borrowing and another round of inflation.

While the headlines are all about the Fed’s economic outlook and the possibility of rate cuts, and while the stock market cheers the possibility of lower interest rates, the reality is a bit more complex.

Yes, a Fed rate cut or two will lower the yields on T-bills and CDs, penalizing savers. But borrowers — whether on credit cards or mortgages — are not likely to see much of that lower rate “gift.”

While the pundits and politicians may react positively to a Fed cut, the real power lies in the global bond market — and its willingness to fund our every-growing debt. That’s where interest rates are really set. And that’s the Savage Truth.

========

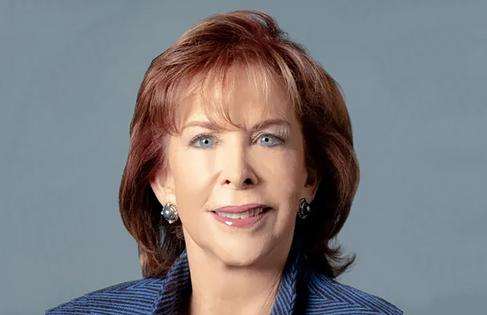

(Terry Savage is a registered investment adviser and the author of four best-selling books, including “The Savage Truth on Money.” Terry responds to questions on her blog at TerrySavage.com.)

©2025 Terry Savage. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments